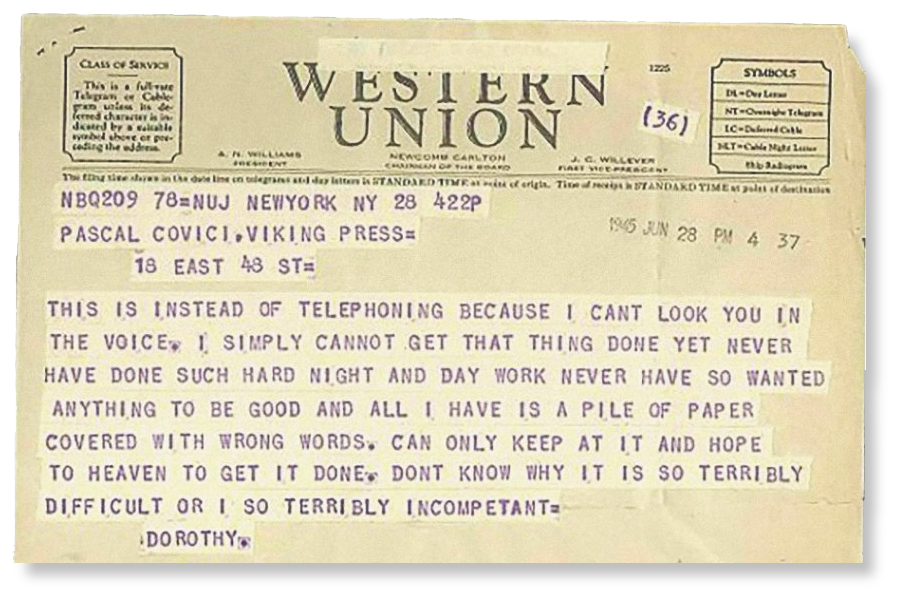

In June 1945, Dorothy Parker telegrams her editor to inform him she has writer’s block:

Via Letters of Note.

Official website of the author

In June 1945, Dorothy Parker telegrams her editor to inform him she has writer’s block:

Via Letters of Note.

“You will no doubt remember a fair-haired crew-cut lad…” In the spring of 1960, Anthony Gilchrist, an old army buddy of Toronto Maple Leafs coach Punch Imlach, recommends a 12-year-old prospect named Bobby Orr. The Maple Leafs’ response is here. The whole story is told here. (Via Pension Plan Puppets.)

Envelope illustrated by Edward Gorey. (via)

“This is the theory… that anything that is art… is presumably about some certain thing, but is really always about something else, and it’s no good having one without the other, because if you just have the something it is boring and if you just have the something else it’s irritating.”

— Edward Gorey

Via Letters of Note.

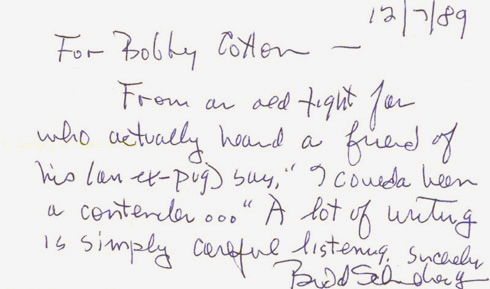

A note from screenwriter Budd Schulberg to a fan, jotted on the back of an index card, explains the origin of the famous line from “On the Waterfront.” The note reads:

12/7/89

For Bobby Cotton —

From an old fight fan who actually heard a friend of his (an ex-pug) say, “I coulda been a contender…” A lot of writing is simply careful listening.

Sincerely,

Budd Schulberg

Now, about that one-way ticket to Palookaville…

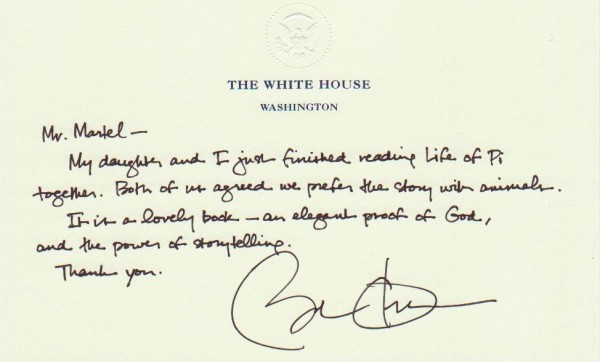

Canadian author Yann Martel received this note from President Obama, out of the blue, about his novel Life of Pi. (Full story here. Larger image here. Via.) Canada’s own prime minister, on the other hand, “sounds and governs like one who cares little for the arts,” Martel writes, speculating that the prime minister may feel he is too busy.

To read a book, one must be still. To watch a concert, a play, a movie, to look at a painting, one must be still. Religion, too, makes use of stillness, notably with prayer and meditation. Just gazing upon a still lake, upon a quiet winter scene — doesn’t that lull us into contemplation? Life, it seems, favours moments of stillness to appear on the edges of our perception and whisper to us, “Here I am. What do you think?” Then we become busy and the stillness vanishes, yet we hardly notice because we fall so easily for the delusion of busyness, whereby what keeps us busy must be important, and the busier we are with it, the more important it must be. And so we work, work, work, rush, rush, rush. On occasion we say to ourselves, panting, “Gosh, life is racing by.” But that’s not it at all, it’s the contrary: life is still. It is we who are racing by.

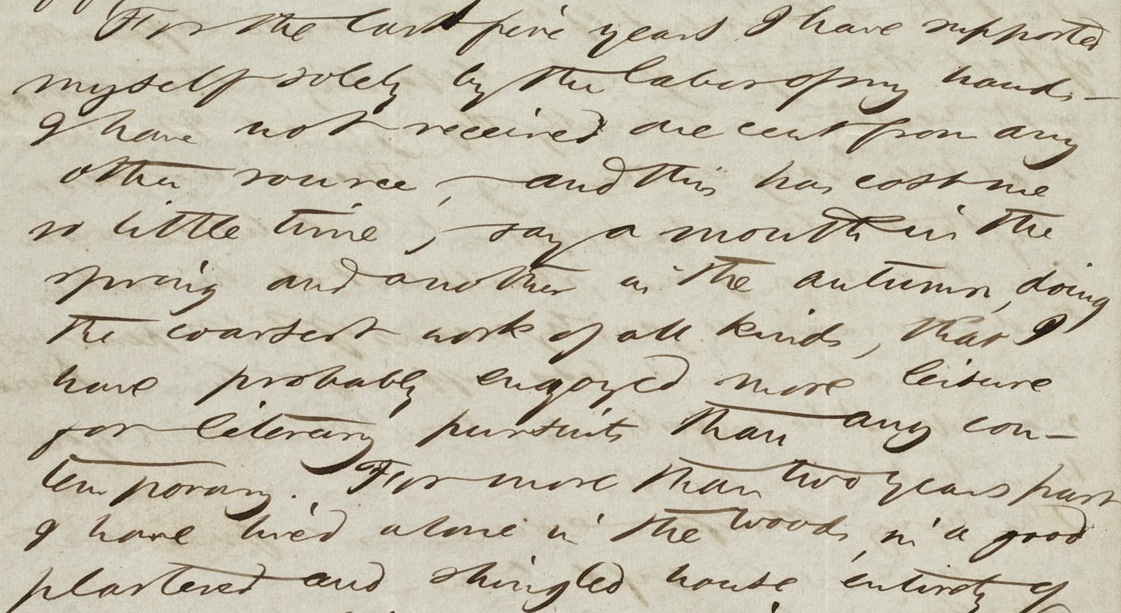

The Boston Public Library in Copley Square, where I often go to write, is running an amazing year-long exhibition called “Cool + Collected: Treasures of the BPL” which highlights some of the rare holdings in the library’s collection. The contents of the exhibit rotate every few months, and the current crop is truly remarkable. It includes original handwritten letters by Louisa May Alcott, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Frederick Douglass, and others. It is a hall of fame of American letters! My favorites are an original working draft of a poem by Walt Whitman, with edits literally cut and pasted on the page, and a four-page letter from Henry David Thoreau to Horace Greeley which begins:

Concord May 19th 1848.

My Friend Greeley,

I received from you fifty dollars today. —

For the last five years I have supported myself solely by the labors of my hands — I have not received one cent from any other source, and this has cost me so little time, say a month in the spring and another in the autumn, doing the coarsest work of all kinds, that I have probably enjoyed more leisure for literary pursuits than any contemporary. For more than two years past I have lived alone in the woods, in a good plastered and shingled house entirely of my own building, earning only what I wanted, and sticking to my proper work. The fact is man need not live by the sweat of his brow — unless he sweats easier than I do — he needs so little. For two years and two months all my expenses have amounted to but 27 cents a week, and I have fared gloriously in all respects. If a man must have money, and he needs but the smallest amount, the true and independent way to earn it is by day-labor with his hands at a dollar a day. — I have tried many ways and can speak from experience. — Scholars are apt to think themselves privileged to complain as if their lot was a peculiarly hard one. How much have we heard about the attainment of knowledge under difficulties of poets starving in garrets — depending on the patronage of the wealthy — and finally dying mad. It is time that men sang another song. There is no reason why the scholar who professes to be a little wiser than the mass of men, should not do his work in the ditch occasionally, and by means of his superior wisdom make much less suffice for him. A wise man will not be unfortunate. How then would you know but he was a fool?

The letter ends, “P. S . My book” — Walden, presumably — “is swelling again under my hands, but as soon as I have leisure I shall see to those shorter articles. So, look out.” (You can read a transcript of the rest of the letter here.)

The exhibit has other wonderful things, too, posters and prints and rare books and so on. But to me — to any writer or reader, I bet — to see the actual handwriting of these giants of American letters is to feel their presence. The experience is electric.

If you’re around Copley Square, check it out (through June). If not, the whole exhibit is available online, in glorious high resolution, on Flickr. Lord knows what else the BPL has stashed away in the vault. Very cool indeed.