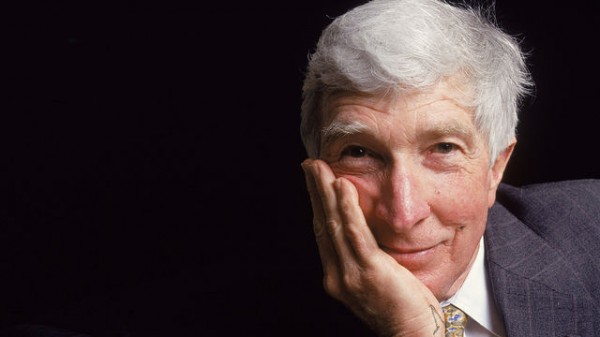

John Updike

Updike: Words that enter in silence and intimacy

“I think ‘taste’ is a social concept and not an artistic one. I’m willing to show good taste, if I can, in somebody else’s living room, but our reading life is too short for a writer to be in any way polite. Since his words enter into another’s brain in silence and intimacy, he should be as honest and explicit as we are with ourselves.”

— John Updike, Hugging the Shore

“Perfection Wasted” by John Updike

And another regrettable thing about death

is the ceasing of your own brand of magic,

which took a whole life to develop and market —

the quips, the witticisms, the slant

adjusted to a few, those loved ones nearest

the lip of the stage, their soft faces blanched

in the footlight glow, their laughter close to tears,

their tears confused with their diamond earrings,

their warm pooled breath in and out with your heartbeat,

their response and your performance twinned.

The jokes over the phone. The memories

packed in the rapid-access file. The whole act.

Who will do it again? That’s it: no one;

imitators and descendants aren’t the same.

— John Updike

Updike’s reader

When I write, I aim in my mind not toward New York but a vague spot a little east of Kansas. I think of the books on library shelves, without their jackets, years old, and a countryish teen-aged boy finding them, and having them speak to him.

The Mystery Writer’s Dilemma

“Hugger-mugger takes a lot of explaining, a lot of diagramming. An additional trouble with it, which keeps the suspense thriller, however skillful and polished, a subgenre, is that the novelist, manipulating his human counters on the board, must keep them somewhat blank, with selective disclosure of their inner lives, lest the killer or mole or whatever be prematurely unmasked.”

— John Updike, “Hugger-Mugger”, The New Yorker, 9.18.06, reviewing le Carré’s novel The Mission Song.

The more you know about a character, the less mystery remains. The less you know about a character, the less believably human he seems. In technical terms, literature requires “round” characters, mystery requires “flat” ones. The trick is to square that circle somehow.

Remembering Updike the Father

John Updike’s son David, also a writer, has a lovely piece in the Times’ Paper Cuts blog. It is a eulogy for his father which he delivered at a tribute in March at the New York Public Library. I found this passage particularly touching:

But for someone who was getting famous, my father didn’t seem to work overly hard: he was still asleep when we went to school, and was often home already when we got back. When we appeared unannounced, in his office — on the second floor of a building he shared with a dentist, accountants and the Dolphin Restaurant — he always seemed happy and amused to see us, stopped typing to talk and dole out some money for movies. But as soon as we were out the door, we could hear the typing resume, clattering with us down the stairs.

My own sons, now five and eight, perceive me the same way, I think. To kids (and others), a writer at work does not seem to be doing much. They can’t understand that I am hard at it whether I am typing like mad or staring blankly out the window. Maybe this is true of all desk-work. Well, at least I have this one thing in common with Updike.

I admit, I feel a strange, vaguely filial attachment to writers of my father’s generation, especially Roth, Updike and Doctorow, whose books I grew up reading. Anyway, read the whole Updike eulogy. You won’t be sorry.

In the meantime, for all my fellow unmentored writers out there, here is Updike in 2004 with some fatherly advice for young writers.

The rest of the interview is here.

I Miss U: Updike Is Gone

I miss John Updike. Not his work. I loved his stories and some of his novels, but lately I admired his books more than I enjoyed them, and sometimes not even that. Anyway, he left more books than I will ever be able or inclined to read.

It is not Updike’s writing that I miss, it is Updike. I miss knowing he was out there, always working, writing, producing. To legions of younger writers, he was the model. He showed us how a professional writer ought to conduct his life, how to comport himself in public and discipline himself at work.

Julian Barnes wrote an appreciative review of Updike’s last books in which he struck on the perfect word for Updike: courteous.

Updike’s fertility was matched by his courtesy — both as a man and as an authorial presence. His fiction never set out to baffle or intimidate. … Updike always treated the reader as a joint partner in the artistic process, an adult equal with whom curiosity and delight in the world were to be shared.

And, Barnes might have added, he always treated his characters with the same decency and sympathy, even when they were behaving badly. It was not in his nature to judge them. (He was an equally gentle book reviewer, a rarity now.)

No particular insight here. It is just sad to see a great man pass.

Updike lives on in cyberspace, at least, as perhaps we all will. For star power, the best clip to emerge since his death was this 1981 interview with John Cheever on the Dick Cavett Show. But I prefer the old, avuncular Updike. (He never seemed elderly — not frail, merely old.) Here he is in 2004, explaining the ability of the novel to “extend the reader’s sympathy,” which is the secret power of fiction.

The rest of the interview is here.