It’s something like a person walking toward you through a mist: Every sentence you write about her makes her a little clearer.

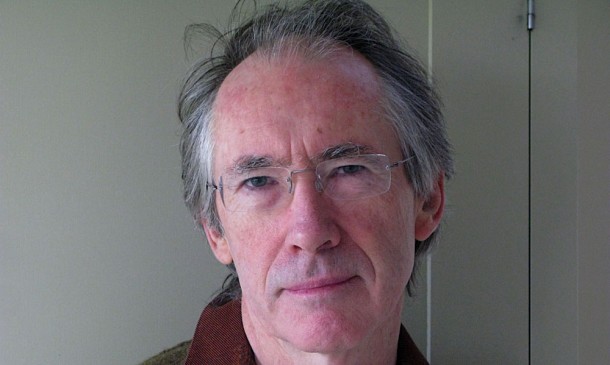

Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan interviewed

Ian McEwan’s writing day

I’m pretty obsessive once I get going. I tend to throw everything at it, and I’m generally rather happy if I’m making progress of 450 to 500 words a day. I work from 9:30 in the morning. If things are going, I see no reason to stop, because I know there’s a point I’ll get to, a moment of hesitation, and a day or a week will pass before I see the way through.

Sometimes, I work late at night, sometimes into the early hours if things are going along. I spend a lot of time at the beginning of a day looking over things from the day before. I was a very early adopter of word processing back in the early ’80s. Being able to constantly correct is good for writers.

I think you do need to come away, somewhere along the line, and let it sit, so you can come back with a completely fresh eye and almost regard it as the work of a stranger.

Three Questions

In her new book, Negotiating With the Dead: A Writer on Writing, Margaret Atwood poses three questions to herself and other novelists: Who are you writing for? Why do you do it? And where does it come from?

Mr. McEwan answered them in quick succession: “I think you could only do it for yourself under the assumption that if you like it, someone else might like it, too. Why do it? I think it’s impossible not to. Not to write seems to me to be a gross rebuke of the gift of consciousness. Where does it come from? You have to dig fairly deeply and relax your control of it … [Fiction] is a random, associative business, just the white noise of daydreaming thought.”

— Ian McEwan, 2002

Ian McEwan on the ideal length of a story

I believe the novella is the perfect form of prose fiction.

How Writers Write: Ian McEwan

From “The Background Hum: Ian McEwan’s Art of Unease,” by Daniel Zalewski, The New Yorker, 2.23.09:

… McEwan keeps a plot book — an A4 spiral notebook filled with scenarios. “They’re just two or three sentences,” he said.…

McEwan said that he never rushes from notebook to novel. “You’ve got to feel that it’s not just some conceit,” he said. “It’s got to be inside you. I’m very cautious about starting anything without letting time go, and feeling it’s got to come out. I’m quite good at not writing. Some people are tied to five hundred words a day, six days a week. I’m a hesitater.”

When McEwan does begin writing, he tries to nudge himself into a state of ecstatic concentration. A passage in “Saturday” describing Perowne in the operating theatre could also serve as McEwan’s testament to his love of sculpting prose:

For the past two hours he’s been in a dream of absorption that has dissolved all sense of time, and all awareness of the other parts of his life. Even his awareness of his own existence has vanished. He’s been delivered into a pure present, free of the weight of the past or any anxieties about the future.… This state of mind brings a contentment he never finds with any passive form of entertainment. Books, cinema, even music can’t bring him to this.… This benevolent dissociation seems to require difficulty, prolonged demands on concentration and skills, pressure, problems to be solved, even danger. He feels calm, and spacious, fully qualified to exist. It’s a feeling of clarified emptiness, of deep, muted joy.

For McEwan, a single “dream of absorption” often yields just a few details worth fondling. Several hundred words is a good day.… He told me, “You spend the morning, and suddenly there are seven or eight words in a row. They’ve got that twist, a little trip, that delights you. And you hope they will delight someone else. And you could not have foreseen it, that little row. They often come when you’re fiddling around with something that’s already there. You see that by reversing a word order or taking something out, suddenly it tightens into what it was always meant to be.”