Boston Public Library

“I have lived alone in the woods”

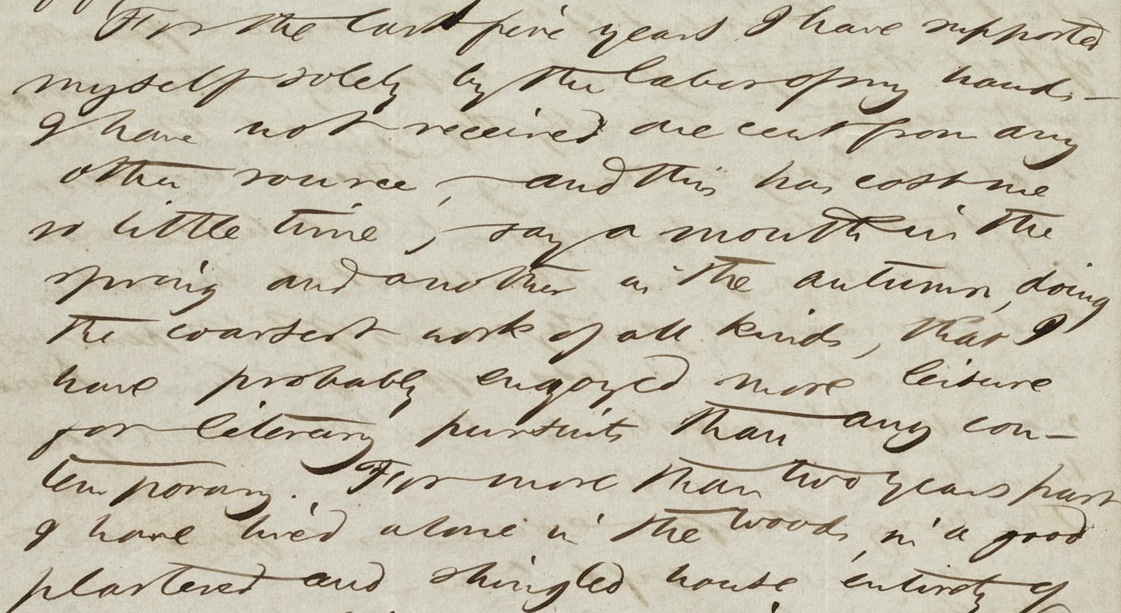

The Boston Public Library in Copley Square, where I often go to write, is running an amazing year-long exhibition called “Cool + Collected: Treasures of the BPL” which highlights some of the rare holdings in the library’s collection. The contents of the exhibit rotate every few months, and the current crop is truly remarkable. It includes original handwritten letters by Louisa May Alcott, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Frederick Douglass, and others. It is a hall of fame of American letters! My favorites are an original working draft of a poem by Walt Whitman, with edits literally cut and pasted on the page, and a four-page letter from Henry David Thoreau to Horace Greeley which begins:

Concord May 19th 1848.

My Friend Greeley,

I received from you fifty dollars today. —

For the last five years I have supported myself solely by the labors of my hands — I have not received one cent from any other source, and this has cost me so little time, say a month in the spring and another in the autumn, doing the coarsest work of all kinds, that I have probably enjoyed more leisure for literary pursuits than any contemporary. For more than two years past I have lived alone in the woods, in a good plastered and shingled house entirely of my own building, earning only what I wanted, and sticking to my proper work. The fact is man need not live by the sweat of his brow — unless he sweats easier than I do — he needs so little. For two years and two months all my expenses have amounted to but 27 cents a week, and I have fared gloriously in all respects. If a man must have money, and he needs but the smallest amount, the true and independent way to earn it is by day-labor with his hands at a dollar a day. — I have tried many ways and can speak from experience. — Scholars are apt to think themselves privileged to complain as if their lot was a peculiarly hard one. How much have we heard about the attainment of knowledge under difficulties of poets starving in garrets — depending on the patronage of the wealthy — and finally dying mad. It is time that men sang another song. There is no reason why the scholar who professes to be a little wiser than the mass of men, should not do his work in the ditch occasionally, and by means of his superior wisdom make much less suffice for him. A wise man will not be unfortunate. How then would you know but he was a fool?

The letter ends, “P. S . My book” — Walden, presumably — “is swelling again under my hands, but as soon as I have leisure I shall see to those shorter articles. So, look out.” (You can read a transcript of the rest of the letter here.)

The exhibit has other wonderful things, too, posters and prints and rare books and so on. But to me — to any writer or reader, I bet — to see the actual handwriting of these giants of American letters is to feel their presence. The experience is electric.

If you’re around Copley Square, check it out (through June). If not, the whole exhibit is available online, in glorious high resolution, on Flickr. Lord knows what else the BPL has stashed away in the vault. Very cool indeed.

There is no sleeping at the Boston Public Library

It is strictly forbidden to fall asleep at the Boston Public Library. I presume this policy is intended to keep the homeless from camping out here, but the homeless know the rules because, well, they camp out here, so it is not the homeless who are primarily affected. It is everyone else. Like me.

Unfortunately, conditions at the Boston Public Library are in all other ways sleep-optimal: quiet, low light, tens of thousands of dull old books. Just about the only way to ward off sleep under these circumstances is eating — but eating, alas, is likewise strictly forbidden at the Boston Public Library.

Security guards, with not much else to do, constantly patrol the library waking up anyone who drifts off. Ever vigilant, they troop past every fifteen minutes or so. Upon detecting a violation, they knock on the table where the offender has laid his head. Then comes a whisper: “No sleeping.” Sometimes even a finger wag.

The BPL sleep police have a thankless task, and it might be better for everyone if we simply changed the rule to “no more than 15 minutes per nap.” The bookkeeping would be unmanageable (how to track when each patron fell asleep? how long to allow between naps until a new 15 minutes is permitted?), but then libraries have always run largely on the honor system.

I will have to leave this matter to the trustees. The injustice of the Boston Public Library’s policy toward drowsy patrons is beyond my capacity at the moment, marooned as I am in the main reading room with a half-edited manuscript, brain-dead from reading the same pages over and over. And over. If I wait for the guard to pass, maybe I can sneak in a quick nap.

The Street Photography of Jules Aarons

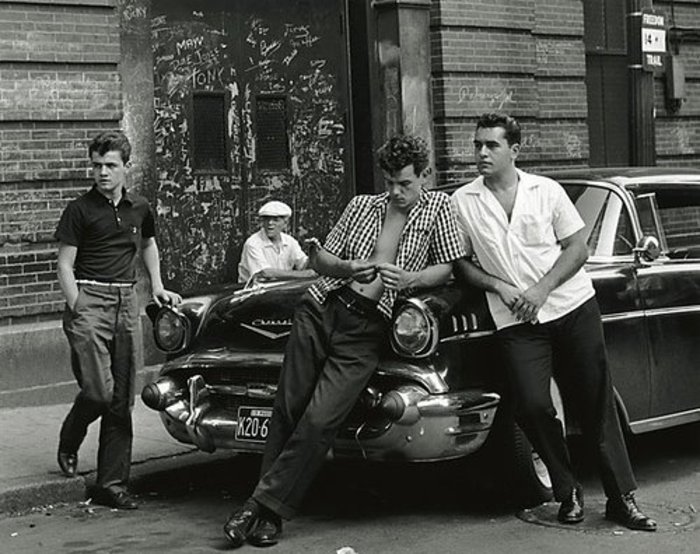

There is a new exhibition at the Boston Public Library of the street photographs of Jules Aarons. The exhibition is located in the Wiggin Gallery in the old McKim Building, just one flight up from the main reading room where where I have been writing every day. The gallery is secluded, and you won’t find much signage or advertising for the exhibit, even in the library itself. The guardians of the BPL apparently have decided to keep this one a secret. That is a shame but not exactly a surprise. Aarons’s work has been underappreciated for a long time now. He is one of the best photographers you’ve never heard of.

I wandered up to the Wiggin Gallery this morning before work, happy to postpone writing a difficult scene that I have been struggling to complete. In the gallery, two women were strolling past the pictures and chatting. They soon wandered off, and I had the entire exhibition to myself. The room was quiet, not the usual library sort of quiet — footsteps, sniffles, sneezes, whispers — but dead quiet. It was an odd place to see these pictures, which are so alive you half expect the people in them to turn to you and speak. (“Get back to work,” they might tell me.)

It is a mystery to me why Aarons’s photographs are not better known. I am not enough of a connoisseur to comment on the technical proficiency of the pictures, but to me they seem expertly composed and printed. Certainly they are very beautiful. Aarons’s street photography has been compared to the work of Lisette Model, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Helen Levitt, and Aaron Siskind, among others. Again, I am not qualified to comment on the comparisons. But I know what I see in these pictures and why I love them: they are alive, authentic, intimate, humane.

Most of the photos in the exhibition date from about 1947-1960, some later. They show ordinary working-class people, often in the West and North Ends of Boston, doing nothing more than chatting on street corners or flirting or lighting a cigarette. Fifty or sixty years later, of course, these people are all gone or transformed by age, but they are utterly alive and present in Aarons’s pictures. To come face to face with them is like traveling back in time. It makes the hair on your neck stand up.

I first discovered Aarons’s work when I was researching The Strangler. His images were always in my head when I closed my eyes and imagined the city during the Strangler period. I even considered approaching him to license one of his images for the book jacket, he so perfectly catches the period feel I was looking for.

Aarons, who died recently at age 87, was never a professional artist. In fact, he was a renowned physicist, an expert in an arcane study that has something to do with radio waves in the atmosphere. Photography was a sort of second career for him. One wonders how a scientific mind could create pictures so soulful.

I suspect that, upon moving to Boston in 1947, Aarons found in the crowded streets of the West and North Ends a subject that reminded him of the Bronx neighborhood where he grew up in the 1920s and ’30s. He was at home in city streets. He seems to have enjoyed the bustle of urban life. His pictures are full of kids playing on sidewalks and women gossiping on tenement stoops and young men leaning on parked cars. I may be biased, but to me he seems especially at home in the streets of this city. His pictures of other places — Aarons traveled and photographed widely — do not have the same vitality and dynamism as the early Boston pictures. His images of Paris and, later, Peru are more abstract, more composed, more consciously artistic. I do not mean that as a criticism. An artist has a right to evolve, to work in a different, cooler style. But I do love the early, raw Boston pictures on display at the BPL.

Aarons’s method was unobtrusive. He used a boxy twin-lens Rolleiflex held at the waist, which gave him an unexpected advantage.

The waist level position allowed me to point my body in one direction and the camera in another. It was important to me not to intrude on the scenes which ranged from card playing in the streets to adults talking to one another.

The effect is like spying on real people, unposed, unself-conscious, unaware of our gaze. It is like visiting a lost Boston — precisely the fantasy I indulged in The Strangler. To see that city here, reanimated in Aarons’s photographs, is an electric experience.

Quote is from Street Portraits 1946-1976: The Photographs of Jules Aarons, Kim Sichel, ed. (Stinehour Press, 2002), p. 10.

Photos: Untitled (West End, Boston), 1947-53 (top). Lounging, North End, 1950s (bottom).

For more info about the exhibition at the Boston Public Library, look here. To see more photos by Jules Aarons, look here and here. There is also a Facebook page dedicated to Aarons here.