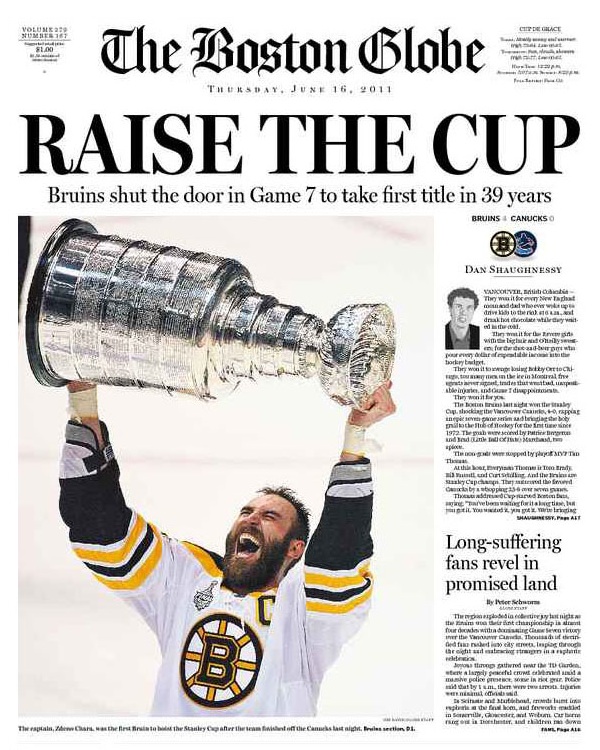

Another shot of today’s Boston Globe. Read the article here.

Boston Globe

John and Me

John Kenney and I have been the best of friends for almost 40 years now, since we met in 9th grade at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston. Now John has published a debut novel, Truth in Advertising, that is hilarious and poignant and has received glowing reviews. (Truth in Advertising also happens to have the greatest book trailer ever. This is what happens when a veteran ad man like John turns his attention to book publicity.)

Recently John and I did a joint appearance at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square (that’s the BPL in the background of that photo), and we met with a reporter from the Globe beforehand to talk about books and how two guys from the same tiny school managed to become novelists. I’m not sure we ever answered that question, really. When we’re together, John and I tend to talk fast, finish each other’s sentences, and laugh a lot. But somehow reporter Bella English managed to turn our rambling conversation into a story, which ran in this morning’s newspaper. Many thanks to Bella and Globe photographer Dina Rudick for capturing such a nice moment. Read it here.

Today’s paper

The latest on Defending Jacob

It’s been a while since I posted one of these updates about Defending Jacob, so here we go.

The biggest news: Warner Brothers has optioned Defending Jacob for a movie. No actors or directors are attached to the project yet. It will likely be a year or so before we have a screenplay, which will make or break the project since it is the screenplay, not the novel, that will attract actors and directors. Now, what I know about the movie business would fit on the head of a pin, so I won’t predict how this will turn out or even whether the movie will be made at all. But every indication is that the producers are intent on making this happen. Stay tuned.

Last week, Defending Jacob was published in the UK. My English publisher, Orion, has orchestrated a phenomenal publicity effort. Luckily, I will be in London in April to see it (and to drop by the London Book Fair, briefly). The first reviews from England have arrived as well, all quite favorable. In The Times, Marcel Berlins wrote that Defending Jacob is “worthy of being mentioned in the same breath [as Presumed Innocent], which is a high compliment.” It certainly is.

Another exciting aspect of this whole adventure has been foreign sales. Defending Jacob has sold in nineteen foreign countries, an absurd number. Now, the trouble with selling so many foreign-language editions is that sooner or later you run out of places to keep selling. Which is why it was so remarkable when we sold the book in Macedonia last week. Because, well, it’s Macedonia. The advance will barely cover a dinner out with my family, and the print run probably will be around 500 copies. Still, I would bet that more American novels are optioned for film than are translated into Macedonian, so let’s pause to savor this milestone, too.

Finally, yesterday morning was a remarkable one here in Boston, where I scored a publicity twofer. First, my hometown newspaper, the Globe, ran an interview with me — and put my mug at the top of page one. This is the very definition of a slow news day, one would think, but there it was. And second, I appeared on the popular morning drive-time show “Matty in the Morning.” The show’s host, Matt Siegel, is a Boston institution and a genuine, enthusiastic fan of Defending Jacob. (You can listen to the interview here.) So Bostonians on their way to work yesterday could hardly escape me.

What a long, strange trip it’s been.

Missing the West End

Architecture critic Robert Campbell has a nice essay in today’s Boston Globe asking “What makes the memory of this neighborhood so durable? Why do the people, half a century later, still feel that they are members of it?” Of course, the demolition of the West End figures prominently in my novel The Strangler. (Photos: Boston Globe.)

(Images: Boston’s old West End under demolition, ca. 1958-60.)

Front page

Robert Campbell on Boston’s Human Scale

Boston’s Old State House … was a perfectly normal-sized building when it was erected, in 1713. But today, surrounded by skyscrapers, it is completely transformed. It possesses a new charm, a charm its architect could never have envisioned: the charm of a tiny jewel or an exquisite ivory carving. Or a child. Among the tall, blank, dark buildings that surround it, the Old State House, with its slightly loony ornaments — a lion and a unicorn — resembles a child in Halloween costume being escorted around the neighborhood by the FBI.

What is true of the Old State House as a building is equally true of Boston as a city. Once Boston, too, was a city of average scale. That’s not the case anymore, not when you compare Boston with the typical American megalopolis, with its vast, bleak stretches of freeway and strip malls. By contrast, we’ve become Tiny Town.

Quite literally so. Boston comprises just 46 square miles of total area. Phoenix is 324, Los Angeles, 465, Honolulu, 596. The new Denver airport is bigger than all of Boston. You could put Louisburg Square in the center strip of many American downtown arteries and forget where you’d left it; it would resemble a minor traffic island. Or take our so-called skyscrapers. No fewer than 12 other US cities boast towers higher than the Hancock, our tallest. Chicago and New York between them have 22. There are several reasons why our buildings are smaller, the most important of which is that most of Boston’s subsoil is muck, not bedrock like Manhattan’s. By the time technology had solved the foundation problem, Bostonians were used to their smaller scale.…

[O]ur perception of scale has a lot to do with our life cycle as human beings. We were all small once, and we all got bigger. In that sense, we are all Alice in Wonderland: In our imaginations and our dreams, we’re always growing and shrinking. When we were little, a table was huge; we couldn’t see over the top of it. The memory of being so overwhelmed is one reason we enjoy miniatures, like doll houses and architectural models.… Why else do we flock to the famous “Main Streets” at Disneyland and Walt Disney World? All the buildings along these streets are built at three-quarters the size they would be in real life. The Disney people always get us right: In a world grown too big, we gravitate to a street that is just a little bit too small. It makes us feel more important, and it makes the world feel more manageable.

…When the “wrong” size is too big, it may command awe. When it is too small, it will often inspire love.

Boston, more than any other major American city, is a place that is filled with opportunities for that kind of affection.

Robert Campbell, “Small Wonders”