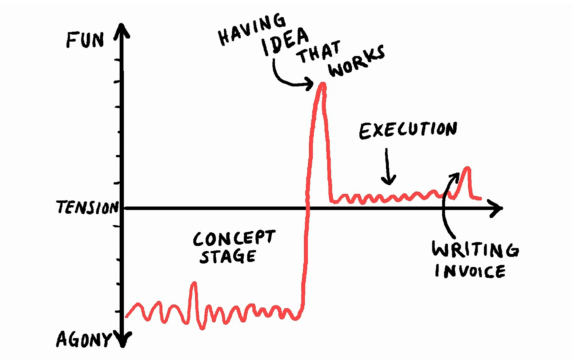

This is a slide from designer/illustrator Christoph Niemann’s charming recent talk at Creative Mornings. Substitute “Sending Manuscript to Editor” for “Writing Invoice,” and you pretty much have the writing life. Watch the whole talk if you have a few minutes. (Via Brain Pickings.) For the record, I am currently mired in the agony of the concept stage … still.