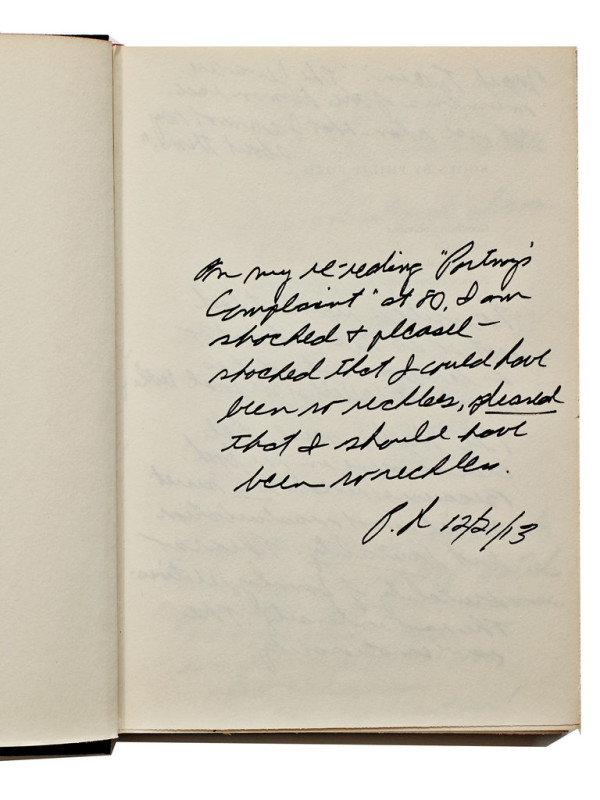

A note by Philip Roth, written in a first edition of Portnoy’s Complaint, which he recently reread after 45 years.

Writing

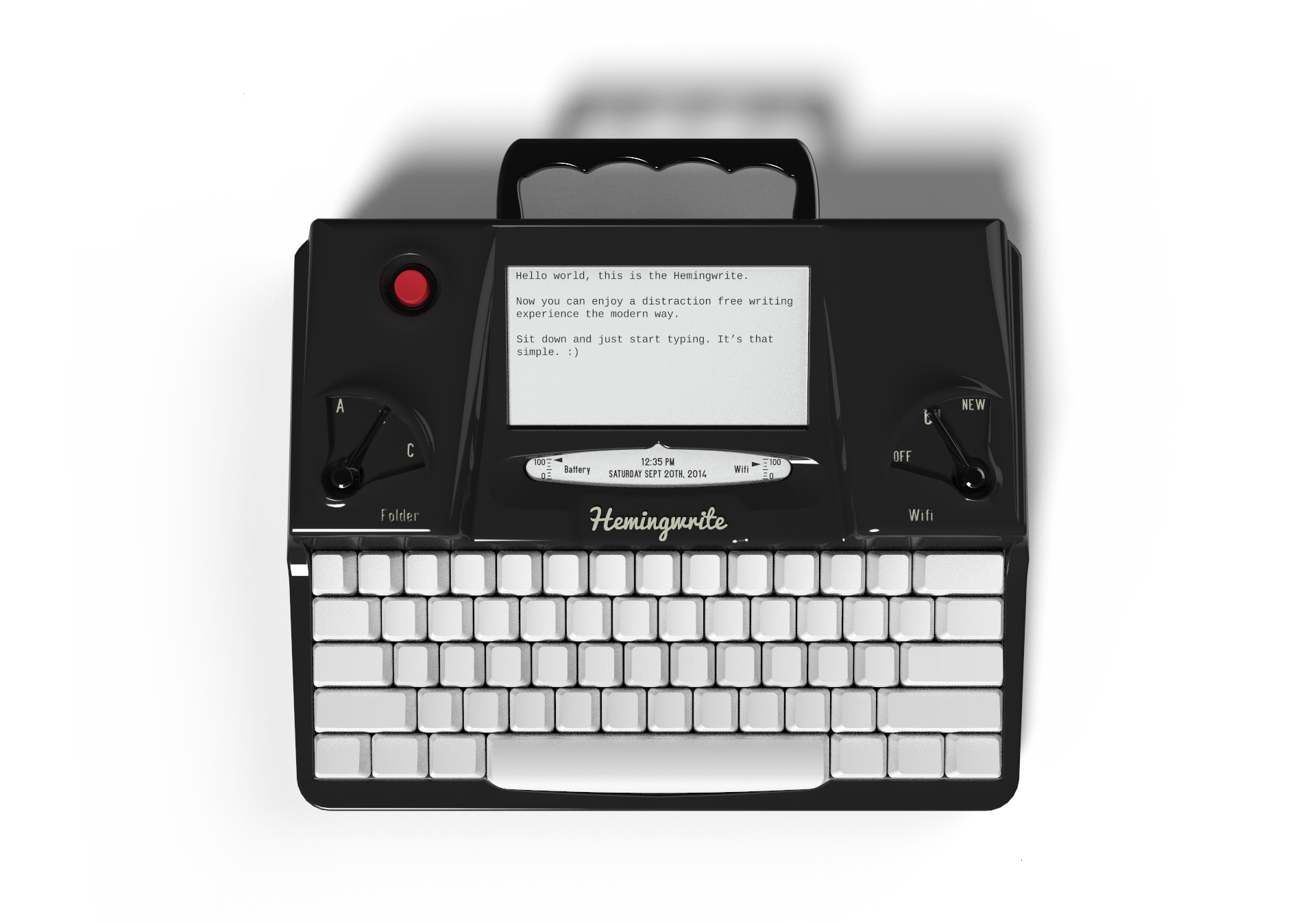

Hemingwrite

I’m intrigued by this new device, called the Hemingwrite. Currently under development, it is a sort of typewriter for the internet age, a simple plain-text word processor with wifi capability that allows it to sync documents with Google Docs and Evernote. That is a perfect combination. It lets jittery, easily distracted writers like me do the one thing we absolutely must — disconnect from the web — while still providing the benefits of cloud syncing and backup. I am not crazy about the over-the-top retro design, which feels self-conscious, but I hope the machine makes it into production, whatever its final design might be. I’d love to try one. For years I have used a variety of devices to shut myself off from the internet while writing: an old, pre-wifi ThinkPad, a simple keyboard device called an AlphaSmart Neo (now lamentably discontinued). This could be a useful tool for gadget-heads like me whose gadgets, alas, tend to get in the way.

Calvino #1

[M]ost of the books I have written and those I intend to write originate from the thought that it will be impossible for me to write a book of that kind: when I have convinced myself that such a book is completely beyond my capacities of temperament or skill, I sit down and start writing it.

Calvino #2

One starts off writing with a certain zest, but a time comes when the pen merely grates in dusty ink, and not a drop of life flows, and life is all outside, outside the window, outside oneself, and it seems that never more can one escape into a page one is writing, open out another world, leap the gap.

Calvino #3

Instead of making myself write the book I ought to write, the novel that was expected of me, I conjured up the book I myself would have liked to read, the sort by an unknown writer, from another age and another country, discovered in an attic.

Resisting the present

To judge by the clock, the present moment is nothing but a hairline which, ideally, should have no width at all — except that it would then be invisible. If you are bewitched by the clock you will therefore have no present. “Now” will be no more than the geometrical point at which the future becomes the past. But if you sense and feel the world materially, you will discover that there never is, or was, or will be anything except the present….

For the perfect accomplishment of any art, you must get this feeling of the eternal present into your bones — for it is the secret of proper timing. No rush. No dawdle. Just the sense of flowing with the course of events in the same way that you dance to music, neither trying to outpace it nor lagging behind. Hurrying and delaying are alike ways of trying to resist the present.

Twain on “show, don’t tell”

Don’t say the old lady screamed. Bring her on and let her scream.

Mark Twain

The virtues of hackery

Mario Puzo thought he was slumming when he wrote The Godfather. He was broke, an aspiring literary novelist with some respectful reviews but not many sales, and he hoped that a thriller about the mob might make a quick buck. … In fact, the writing of The Godfather released something fresh in Puzo’s imagination—a streak that was both potboilerish and also a little baroque—and if the result wasn’t “literary,” exactly, it was great pop fiction. … The director of those movies, Francis Ford Coppola, originally felt about them the way Puzo felt about his book; he considered them commercial hackwork compared with his more “artistic” films like “Rumble Fish” and “One From the Heart.” And as in Puzo’s case, that attitude actually proved liberating, enabling Mr. Coppola to adopt a style that was grander and more operatic—more “epic,” to use the Hollywood term—but also less arty and self-conscious than the one he used for his more personal projects. Mr. Coppola’s “Godfather” enterprise went off the rails in “Part III,” which came out in 1990, when self-importance again seemed to overtake him (along with his star, Al Pacino) and he was no longer in touch with the story’s roots in pop culture and gangster-movie mythology.

I suppose there is a more compelling case to be made for artistic ambition, but it is worth remembering that great, lasting work often comes when artists aim low.