Writing

Philip Roth interviewed on “Fresh Air”

TERRY GROSS: So if [writing] is so hard, why do it?

PHILIP ROTH: Well, that’s a question I ask myself too. I’ve been doing it since 1955. So that’s 55 years. It’s hard to give up something you’ve been doing for 55 years, which has been at the center of your life, where you spend six, eight, sometimes ten hours a day. And I always have worked every day, and I’m kind of a maniac, you know. How could a maniac give up what he does? Tell me.

GROSS: Is that seven days a week, like Saturday and Sunday?

ROTH: Yeah, I usually do, yeah.

GROSS: That is obsessive.

ROTH: Maniacal.

GROSS: Maniacal?

ROTH: Give it its right name. It’s maniacal.

Via nprfreshair

Orwell: Why I Write

All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.

George Orwell, “Why I Write“

Roth: “The ordeal is part of the commitment”

“I have a slogan I use when I get anxious writing, which happens quite a bit: ‘the ordeal is part of the commitment.’ It’s one of my mantras. It makes a lot of things doable.”

Drawing Circles

The other day I blogged about the story of Giotto’s O: A messenger from the Pope arrived in Giotto’s studio in Florence one morning. He asked for a drawing to prove the artist’s skill to the Pope, who was seeking a painter for some frescoes in St. Peter’s. As Vasari tells the story, Giotto “immediately took a sheet of paper, and with a pen dipped in red, fixing his arm firmly against his side to make a compass of it, with a turn of his hand he made a circle so perfect that it was a marvel to see it.” Of course, Giotto got the job.

I had never heard the story until I ran across it online recently. It stuck in my mind, a romantic parable of what artistic mastery means. To paint an angel, first you must learn to paint a perfect circle — something like that.

Curious, I wandered around the web looking for more information about Giotto and his circle, and, in the hopscotch way of the web, I found an interesting blog post that linked Giotto’s O to a different sort of circle, the ensō, the asymmetric circle of Japanese Zen calligraphy.

In Zen Buddhist painting, ensō symbolizes a moment when the mind is free to simply let the body/spirit create. The brushed ink of the circle is usually done on silk or rice paper in one movement (but the great Bankei used two strokes sometimes) and there is no possibility of modification: it shows the expressive movement of the spirit at that time. [Wikipedia]

The imperfection of the circle — the asymmetry, the visible brush trails, the blobs of ink — is the point. In its very “flaws,” ensō embodies a traditional Japanese aesthetic, fukinsei (不均整), asymmetry or irregularity. Garr Reynolds (one of my favorite bloggers) explains,

The idea of controlling balance in a composition via irregularity and asymmetry is a central tenet of the Zen aesthetic. The enso … is often drawn as an incomplete circle, symbolizing the imperfection that is part of existence.

So these two famous circles, Giotto’s O and the ensō, embody very different aesthetic ideals.

Giotto’s circle is precise mechanical perfection, “a circle so perfect that it was a marvel to see.” Even his technique is machinelike: he pins his elbow to his side, turning his arm into a virtual compass.

Vasari adds another detail, as well. In the versions of the story that I initially read, Giotto loads his brush with red paint and paints the circle with a single sweep of his arm. But in Vasari’s telling, Giotto scratches out his circle with a pen (a quill, presumably) rather than a brush. He wants to eliminate even the wavering edge of a brush stroke, the little quivers of the bent bristles.

In writing, that sort of perfectionism is fatal. The very idea of creating “perfect” sentences or stories is paralyzing. No one can write perfectly. I have learned this lesson the hard way. I am a perfectionist by nature. It is no wonder the Giotto story appealed to me. But there are no Giottos in writing. You have to embrace imperfection, you have to accept the little oddities and surprises that emerge in the moment of creation, in the immersive “flow” state that characterizes the best writing sessions. I don’t know the first thing about Zen, but to me the go-with-it philosophy of the ensō feels much truer to the actual experience of writing well. It is not a feeling of abandon; like ensō painting, good writing is never careless or out of control. At the same time, every writer has to accept the little wobbles of his brush, the little traces of his bristles, the funny pear-shape of his ensō. Not because these flaws are unavoidable (though they are) but because they are beautiful.

To a writer like me — who tends to self-edit too much, who sometimes imagines he can write perfectly — the story of Giotto’s O teaches the wrong lesson. I will think of the ensō instead.

The origin of “I coulda been a contender”

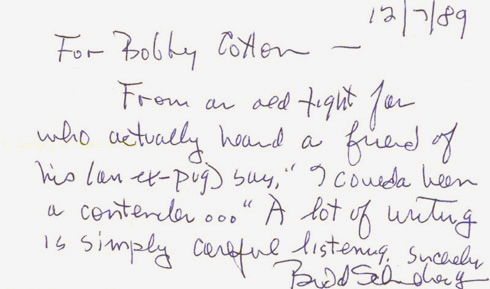

A note from screenwriter Budd Schulberg to a fan, jotted on the back of an index card, explains the origin of the famous line from “On the Waterfront.” The note reads:

12/7/89

For Bobby Cotton —

From an old fight fan who actually heard a friend of his (an ex-pug) say, “I coulda been a contender…” A lot of writing is simply careful listening.

Sincerely,

Budd Schulberg

Now, about that one-way ticket to Palookaville…

Bellow on Inspiration

“You never have to change anything you got up in the middle of the night to write.”

— Saul Bellow (via)

For Writers

A writer at work is about as isolated as it is possible to be. No matter if he is sitting in a crowded Starbucks, no matter how gregarious he may be at other times, when he is writing he is perfectly alone.

I have always welcomed the solitude. Most writers do, I think, otherwise we would not stick with the job very long.

At the same time, the writer’s isolation walls people out in an unhelpful way. Years ago, when I was unpublished and struggling to learn novel-writing (I never saw myself as any other sort of writer), I was eager to watch established novelists at work, to see what the job was all about. But of course the internal nature of the work makes that sort of access impossible. The real work of writing is invisible. Robert Olen Butler put the problem nicely in an interview once:

The one thing that other aspiring artists have over writers is that many of them can view their mentors at work. A painter can sit at the back of a studio and watch her mentor paint, a ballet dancer can watch his mentor rehearse and perform. But you can’t really observe the creative process of a fiction writer. It’s never been seen.

Even now, when every author has a blog and a Twitter feed, there are surprisingly few good peepholes into the daily working lives of writers.

I try to provide such a peephole on this blog. I discuss my writing process, some of the ups and downs of my writing life, the snags I run into as — slowly, slowly — I produce a novel. In conversation I am usually bashful on the subject, and on the blog too I weigh my words probably more than necessary. Still, I’ve been more forthcoming than most authors, I think.

I have gathered up some of that material from the blog in a new page called On Writing. It will appeal mostly to writers, I think, though anyone interested in books may find it worthwhile.

The page has two elements: a collection of quotations which I use as a commonplace book, a place to keep quotes I’ve run across that I like to refer back to; and an index of blog posts that have to do with writing. Both elements — the quotes and the links — are reshuffled every time the page loads, so On Writing will look a little different every time you visit. The idea is to browse at random, to stumble across things serendipitously.

Just to be clear: my purpose is not to teach anyone how to write. I am not so presumptuous. Even if I were willing, what works for me may not work for you. Hell, what works for me one day often does not work for me the next. In the theater, actors used to talk about The Method. For writers there is no such thing. There are as many methods as there are writers. Nobody can tell you what will work for you.

Nor do I think I have anything especially profound or insightful to say about writing. The truth is, I don’t know what the hell I’m doing. No writer does. We are all just feeling our way along, trying to find the sentences that please us, that sound right to our ears. We all tinker constantly with schedules, environments, work habits — anything that seems to help. Believe me: nobody knows how to do this. Nobody has the secret, the one true way.

So the goal here is not to lecture, but to share some of my own thoughts and experiences. It is important for writers to support one another. Writing is not a zero sum game: one writer’s success does not diminish another’s chances. Hopefully this material will help someone out there.