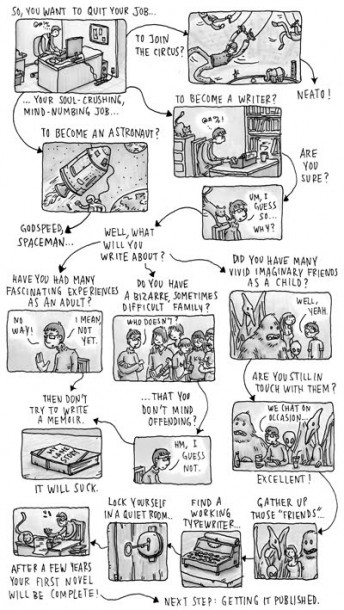

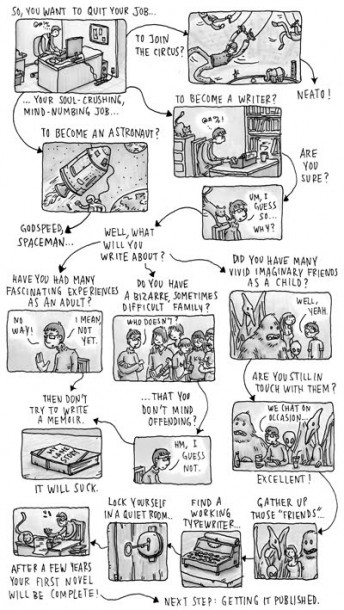

By Grant Snider.

Official website of the author

By Grant Snider.

From Frederick Brown’s definitive biography of Flaubert, a typical day during the writing of Madame Bovary in 1851-56. Flaubert was 30-35 at the time.

Flaubert, a man of nocturnal habits, usually awoke at 10 a.m. and announced the event with his bell cord. Only then did people dare speak above a whisper. His valet, Narcisse, straightaway brought him water, filled his pipe, drew the curtains, and delivered the morning mail. Conversation with Mother, which took place in clouds of tobacco smoke particularly noxious to the migraine sufferer, preceded a very hot bath and a long, careful toilette involving the regular application of a tonic reputed to arrest hair loss. At 11 a.m. he entered the dining room, where Mme. Flaubert; Liline [Flaubert’s niece]; her English governess Isabel Hutton; and very often Uncle Parain would have gathered. Unable to work well on a full stomach, he ate lightly, or what passed for such in the Flaubert household, meaning that his first meal consisted of eggs, vegetables, cheese or fruit, and a cup of cold chocolate.… In June 1852, Flaubert [wrote in a letter] that he worked from 1 p.m. to 1 a.m. A year later, when he assumed partial responsibility for Liline’s education and gave her an hour or more of his time each day, he may not have put pen to paper at his large round writing table until two o’clock or later.

To any writer: Teach yourself to work in uncertainty. Many writers are anxious when they begin, or try something new. Even Matisse painted some of his Fauvist pictures in anxiety. Maybe that helped him to simplify. Character, discipline, negative capability count. Write, complete, revise. If it doesn’t work, begin something else.

— Bernard Malamud (via Paris Review)

Perhaps the most important quality, the one that is most consistently present in all creative individuals, is the ability to enjoy the process of creation for its own sake. Without this trait, poets would give up striving for perfection and would write commercial jingles, economists would work for banks where they would earn at least twice as much as they do at universities, and physicists would stop doing basic research and join industrial laboratories where the conditions are better and the expectations more predictable.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, “The Creative Personality”

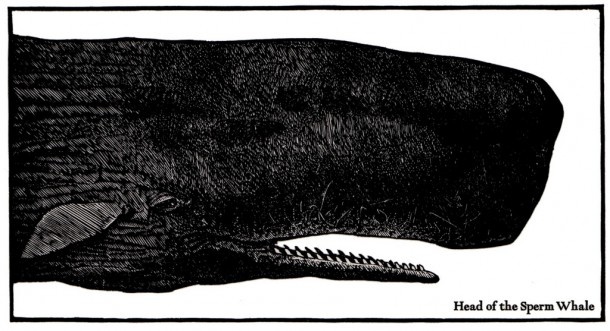

In a famous chapter of Moby Dick, Melville explains the law governing ownership of whales at sea.

It frequently happens that when several ships are cruising in company, a whale may be struck by one vessel, then escape, and be finally killed and captured by another vessel; and herein are indirectly comprised many minor contingencies, all partaking of this one grand feature. For example,— after a weary and perilous chase and capture of a whale, the body may get loose from the ship by reason of a violent storm; and drifting far away to leeward, be retaken by a second whaler, who, in a calm, snugly tows it alongside, without risk of life or line. Thus the most vexatious and violent disputes would often arise between the fishermen, were there not some written or unwritten, universal, undisputed law applicable to all cases.…

I. A Fast-Fish belongs to the party fast to it.

II. A Loose-Fish is fair game for anybody who can soonest catch it.

…What is a Fast-Fish? Alive or dead a fish is technically fast, when it is connected with an occupied ship or boat, by any medium at all controllable by the occupant or occupants,— a mast, an oar, a nine-inch cable, a telegraph wire, or a strand of cobweb, it is all the same. Likewise a fish is technically fast when it bears a waif [ed. note: a pole stuck into the floating body of a dead whale as a marker], or any other recognized symbol of possession; so long as the party wailing it plainly evince their ability at any time to take it alongside, as well as their intention so to do.

I spent ten years writing Oscar Wao, and I definitely didn’t spend the ten years being like, “I’m amazing! This has taken ten years because this much genius requires a decade!” [laughter] I spent the whole time, you know, fucked up, unhappy, really miserable and convinced that I’d ruined the whole thing, and all the stuff you get when you spend a really long time lost in the desert. I think more than anything, my basic lesson as an artist has been humility.… The crazy thing about the arts is it’s not like other stuff where you can build up muscle to help you with the next project. A friend of mine, he’s a surgeon, he’s like a combat surgeon in Iraq, and we grew up together and immigrated together, and he tells me every surgery makes you even more awesome for the next surgery. I’ve never felt that anything I’ve written has made me more awesome. So I think for me it’s going to be a struggle for whatever the next project is, and if you’re an artist and you work long enough at this, you begin to understand your rhythm, and what I’m beginning to understand is my rhythm is very slow. I felt like my first book was just an accident, but what I’m discovering now is that this is my rhythm. I take forever. Friends of mine hear this and they want to fucking throw themselves off a bridge, because the first ten years drove them crazy.… Melville wrote Moby-Dick — does anyone remember how many months it took him? Like fourteen months! Fuck you, Melville!

— Junot Díaz, interviewed by Dave Eggers in The Boston Review

Productive novelists hurry from one project to the next. Lee Child has said that the moment he types the last sentence of a book, he immediately writes the first few sentences of the next one. That manic pace is partly a function of the book-a-year schedule that top-sellers like Lee have to maintain. As a practical matter, if you intend to deliver a book every twelve months, there just isn’t time to slow down between projects.

But there is something else, too. The doldrums between books is a dangerous, depressing time for a writer. In an interview I posted here a long time ago, Philip Roth said, “Without a novel I’m empty. I’m empty and not very happy.” I have that bereft feeling now.

I sent off my last book to my editor a few weeks ago. Since then, I have been trying to assemble the first stirrings of the next book, all the notes, clippings and research, all the vague notions that I have been collecting for the project over the years. These scraps don’t mean much. When I look them over now, they don’t cohere. Whatever glimmer of inspiration I saw in them is long gone. But I keep organizing my old notes, studying them, rereading them, because they are the only clues I have about what this dim intuition in my head is leading to. Also, honestly, I don’t know what else to do. How, exactly, do I go about finding the story in all this mess?

How to start a new book is an especially fraught subject for me. I have had long gaps after each of my novels, which has hurt me commercially. My first English publisher, Transworld, dropped me because I was not “writing regularly.” But the problem has not been slow writing. The problem has been projects that were badly chosen, badly planned, or simply abandoned too soon — healthy babes smothered to death in the crib. I have learned the hard way how crucial this inception stage really is. Choose the wrong story or build the right story the wrong way, and you may wind up writing yourself into a corner or (every writer’s nightmare) abandoning a half-finished manuscript. The time-penalty for a mistake like that is measured in months, even years.

So I want to move quickly this time, but I do not want to make a mistake. Hesitation is fatal, but lack of hesitation can be, too. The trick, as John Wooden put it, is to “move quickly but don’t rush.”

In the meantime, tonight is New Years Eve. The clock will be ticking especially loudly for me.

What people are ashamed of usually makes a good story.

— F. Scott Fitzgerald