My friend Doug Cornelius has a nice review of Mission Flats over at his blog. Doug also writes for GeekDad over on Wired, among his various other web platforms. Check him out. And thanks, Doug!

My Books

Book 3 Update: The Final Push

Toward the end, writing a novel is a race against the clock. Deadlines that once seemed absurdly far off suddenly loom into view. The story itself demands that you write faster, too, with more urgency, so that the reader will feel the acceleration and she will be pulled along with you to the finish. That is the stage of writing I am entering now, and I am dreading it.

I am behind schedule, as usual. It seems unlikely I will make my internal deadline of January 1 for a completed manuscript, but I am going to kill myself trying. The real deadline, when the manuscript is actually due on my editor’s desk (well, in her email inbox), is April 1, and the cost of missing it — the loss of my publishers’ trust, the loss of future prospects — is simply too high for a midlist, erratically productive writer like me to survive at this point in my career. So the internal deadline remains January 1. That should leave me enough time for rewriting and polishing. Alas, November and December will not be much fun for me.

The good news is that the book itself is working. I have never been one of those writers who feel, as many claim to, that the characters come alive and act on their own while the writer merely watches, furiously writing down the action like a medium at a séance. It is always work for me, always an uphill push. Still, when it is right, something happens: the material feels rich, it generates ideas organically, the direction of the story becomes more obvious. With this book, thankfully, that something has happened.

In terms of pages, I am probably only halfway through the manuscript, maybe a bit further. In terms of story, I have reached act three, the final build-up to the climax. The story concerns a Boston prosecutor named Andy Barber whose teenage son is accused of murder. (A film producer who read the existing manuscript described it in perfect Hollywood-speak as Presumed Innocent meets Ordinary People, which, I am embarrassed to say, is pretty close.) As act three opens, the case goes to trial. I have never written a courtroom sequence before, but I am confident I can. I have been in court many, many times in my prior life as a prosecutor. More important, the courtroom is such an inherently dramatic arena and trials are so scripted and rules-bound that there is a ready structure for the storytelling. So again, this is all to the good.

I continue to labor over the title. The working title remains Blood Guilty but I detest it. This is a bigger problem than you might imagine. The title crystallizes the story in my mind. Not having a title makes the whole project feel foggy and uncertain to me. I have churned up alternatives — Seed, The Good Father, In Our Blood, many others — but each seems worse than the last. It is some comfort to remember that Fitzgerald never liked the title The Great Gatsby for his masterpiece and he tried to change it right up to the time the book went to press. The Great Gatsby, it must be admitted, is not a great title, so maybe this is less of an issue than it seems at the moment.

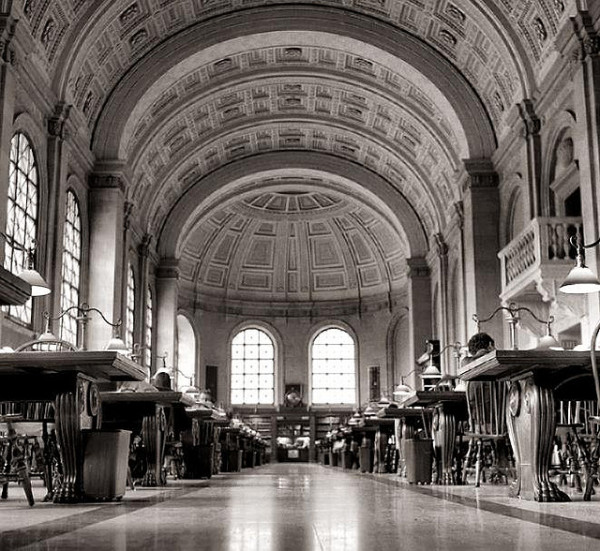

That is where it stands. I am turning for home. It is a difficult stage in the process, but then they’re all difficult. I am back to writing every morning at the Boston Public Library reading room (pictured above), though my old quota of a thousand words a day is not going to get it done anymore. I am now just writing as much as I can every day until I run out of gas.

I am not complaining. It is a privilege to do what I do. There are only a handful of full-time novelists on the planet, meaning novelists who make a decent living at it without the need for a day job. So I am blessed and I understand that. Still, these next eight weeks are going to suck.

Photo: “Study” (main reading room of the Boston Public Library) by Haydnseek (link).

A Favorite Review

I don’t want to turn this blog into a sellathon for my books. I am quite bad at self-promotion, probably because it makes me so uncomfortable.

But as I’ve been transferring material from my old web site to this new blog, I ran across a review of The Strangler that I particularly relished and want to share here. It was not widely read, I am sure. It appeared in Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, the professional journal of the local bar, on May 28, 2007. I would have missed it myself if some lawyer friends had not pointed it out to me.

I love this review because it was written by a veteran criminal defense lawyer who actually knew Boston in the Strangler era and because it focuses on the accuracy of the historical detail. Factual accuracy is lost on most readers. They show up for the story, as they ought to do. The setting may seem vivid and convincing to them, but they have no way of judging its authenticity and they don’t give a damn anyway.

When I first took up writing about crime, as a former A.D.A. I resolved that my books would be accurate to the last detail. They would be “true.” Cops and lawyers would pick them up and nod their heads in recognition: “That’s how it really is!” I quickly learned how foolish that was. It is more important to tell a good story than an accurate one, better to be credible than authentic, realism is not reality, etc., etc. These are basic rules. But the truth is, authenticity still matters to me, probably more than it should.

Local writer pens novel of killer’s stranglehold on Boston

By Norman S. Zalkind

“The Strangler,” by Newton’s own William Landay, is an extraordinary portrayal of the underbelly of Boston in the early 1960s. It is Landay’s second contribution to the crime-novel genre, his first being “Mission Flats” (the fictional name of a gritty city neighborhood in Boston), in which he showed his skill at turning out a page-turner.

Having grown up in and around Boston when the events portrayed in Landay’s latest work took place, I am amazed at his ability to accurately reconstruct one such history-making event: the tragic destruction of Boston’s West End neighborhood and its replacement with a so-called urban-renewal project that destroyed a vibrant, working-class immigrant community.

Landay’s story of an infamous strangler feels like the Boston-based movie, “The Departed,” with non-stop violence seen through the eyes of the three Daley brothers: Ricky, the skilled burglar; Michael, the Harvard-trained lawyer; and Joe, the World War II veteran, compulsive gambler and Boston cop who is corrupted by his addiction.

The Boston Strangler investigation was on everyone’s mind in the Boston of 1963. A killer had taken the lives of a dozen victims, and the city was shaken.

Landay, a Boston College Law School graduate and a former assistant district attorney, postulates the theory that Albert DeSalvo, who confessed to the crimes (and was later murdered in prison), was really not The Strangler. Many in the legal community agree with Landay’s thinking.

But this attorney/author dismisses any suggestion that his background in criminal justice might explain his facility for writing on that topic. “I am leery of my own credentials,” he told The Boston Globe in a recent interview. “People look at me and focus on the fact that I was an assistant DA and project all sorts of things on my books, as if that is some sort of guarantee of authenticity. But the credential guarantees nothing.”

Nonetheless, Landay can spin a tale of murderous intrigue. “The Strangler” is fast-paced, filled with relentless suspense and mayhem. The Daley boys’ father, a Boston police officer, is killed under mysterious circumstances, and the brothers suspect their father’s partner, Conroy, of the killing.

The story becomes more complicated when, after the father’s death, Conroy moves in with Joe Daley Sr.’s widow, Margaret. More complications arise when Margaret is attacked by a man the sons believe is the real “Strangler.”

Joe, the cop, becomes a pawn for the mob, but he is both good cop and bad cop at the same time. The good-cop side of Joe leads him to investigate the forced removal of families from the West End. When he stands up to the mob, and doesn’t get his burglar brother Ricky to return diamonds he allegedly stole, Joe and Ricky become objects of mob contracts.

Former ADA Landay is able to capture the criminal-defense scene the way it was in the early 1960s. The defense bar was dominated by natives of Massachusetts — and Boston in particular. The colorful F. Lee Bailey and others of his ilk — Joe Balliro, Bill Homans and Paul Smith, among them — could definitely have been the lawyer characters in this novel. Boston’s non-white-collar criminal defense bar is today still dominated by locals, but they are nothing like their legal forebears of 40 years ago.

Landay’s constant use of local street language reveals his in-depth knowledge of a storied era and brings color and humanity to his writing. He reveals his relative youth only when he has the Boston detective carrying 9 mm firearms instead of the .38-caliber guns that the police used in that earlier time.

This lawyer novel is most impressive in its focus on crime and the city. It is a great fast read that unfolds like a screenplay. You will be impressed with the way the writer integrates homicide investigations, political corruption, mental illness, organized crime, love, humor and much more. ♦

Norman S. Zalkind is a longtime Boston criminal-defense attorney.

As for that gun, it is the one detail of the book that I changed when The Strangler was reissued in paperback. Joe Daley now carries a .38 as he should, thanks to Mr. Zalkind.

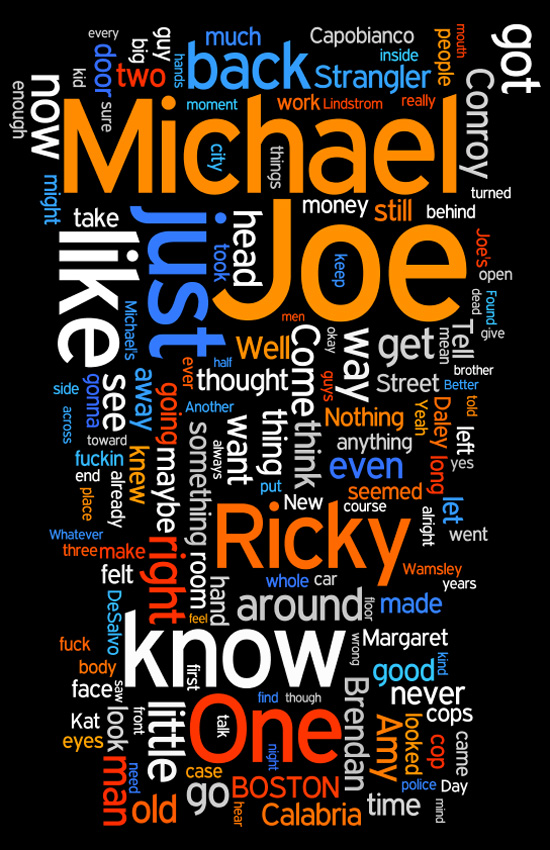

A “Strangler” Word Cloud

Just for kicks, courtesy of Wordle.net, here is the text of The Strangler displayed as a word cloud, a visual representation of the most frequently used words in the novel. Not sure how much this tells you, really. The characters’ names dominate, as you might expect. Other prominent topics show up as well: Boston, cops/police, brother. The surprise is that the F-word appears, and not once but twice, including the all-important adjectival or gerund form, fuckin’. I know some authors shy away from profanity even in books that are violent or sexually graphic or otherwise aimed at adults. But to me it seems phony to portray street thugs speaking the Queen’s English, and perverse to blush at using a dirty word but not at lurid descriptions of gory violence. Even so, I hadn’t realized I used the word that much.

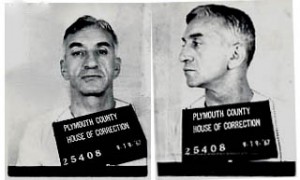

Angiulo, Barboza and fictionalizing the Boston Mob

The animating idea of The Strangler was to recreate Strangler-era Boston, to bring the lost city to life so convincingly that readers would have the immersive three-dimensional experience of actually being there, walking the streets, brushing shoulders with the people. Period authenticity was important: the original working title of the book was The Year of the Strangler.

Of course reanimating the actual city required that a few prominent Bostonians appear undisguised, or nearly so, including gangsters, cops, and politicians. In the original draft, these characters were accurately named and described. The mob boss Capobianco, for example, was called by his real name, Gennaro Angiulo. The historical Gerry Angiulo ran the Boston mob during my childhood in the 1970s. In 1963 and ’64, when The Strangler takes place, he was just consolidating his power.

On the eve of the book’s publication, I got a call from a lawyer at Random House asking about some of these historical figures, including Angiulo. “Is he still alive?” the lawyer wanted to know. Apparently libel laws are stricter when the subject is living. Angiulo was 87 years old then, but still alive in a federal prison. So his name had to be changed. To further insulate the book from a libel charge, Angiulo had to be mentioned by name in the book so we could plausibly deny that my character Capobianco was an Angiulo stand-in. After all, we could argue, there is Angiulo standing next to Capobianco — how could they be the same person? All this sensitivity about the man’s reputation seemed a little ridiculous to me. How was it possible to libel a murderer and convicted mafioso like Gerry Angiulo? But I did not insist, and shortly before publication the character was rechristened Charlie Capobianco. Still the facts remain: the novel’s description of a “born bookie” who became a mob boss — his physical appearance, his biography, his North End headquarters, his bookmaking operation — all are meticulously faithful to the life of Gerry Angiulo. (The libel issue is moot now. Gerry Angiulo died at the end of August, at age 90. His funeral procession required a flatbed truck to carry the 190 bouquets of flowers.)

[Read more…] about Angiulo, Barboza and fictionalizing the Boston Mob

Biocriminology

“There’s certainly a brain basis to crime … the brains of violent criminals are physically and functionally different from the rest of us.”

— Adrian Raine

A burgeoning science suggests that crime is caused in part by biological factors, that is, by traits inherited through DNA or by the brain malfunctioning in very specific ways. Adrian Raine, a “neurocriminologist” and chair of the criminology department at the University of Pennsylvania, says,

“Seventy-five percent of us have had homicidal thoughts. What stops most of us from acting out these feelings is the prefrontal cortex…. When the prefrontal cortex is not functioning too well, maybe an individual, when angry, is more likely to pick up a knife and stab someone or pick up a gun.”

Some criminals, it seems, are biologically different from us.

“People who are psychopaths or who have antisocial personality disorder are literally cold-blooded. They have lower heart rates. When they’re stressed, they don’t sweat as much as the rest of us. They don’t have this anticipatory fear that the rest of us have.”

Obviously I am not qualified to judge the science. But if it is true, as seems increasingly likely, that “freedom of will is not as free as you think,” as Professor Raine puts it, that fact would undercut the entire philosophy of our criminal law, which is that we punish the guilty mind, the mens rea — the conscious, purposeful decision to commit a crime. Where the defendant’s free will or judgment is compromised, because he is drunk or insane or a child, for example, generally the law attaches a lesser degree of culpability, sometimes no culpability at all (the proper finding for an insane defendant is “not guilty by reason of insanity,” not “guilty but insane”).

My third novel, to be published in February 2012, turns on just these sorts of questions. The story involves a father whose teenage son is accused of a murder, a crime that may have been triggered by the boy’s genetic inheritance — a “murder gene.” How should we think of such a criminal? It is not simply a question about crime or criminal law. It is the fundamental subject of crime novels, it is the reason we read them, to ask: What does crime tell us about ourselves and our nature? Modern neuroscience and genetics are beginning to provide answers Dostoyevsky could never have imagined.

Here is Professor Raine on the legal and ethical implications of neurocriminology:

Inside “The Strangler”: The New Boston, 1963

One of the frustrations in writing a historical novel like The Strangler is that so much of your research never sees the light of day. When the book is done, all those index cards so lovingly compiled get wrapped up in a rubber band and tossed into a drawer, and the reader is left to wonder which bits of the story are fact and which are fiction. I thought I might pull some of those notes out of the drawer again and, over the next couple of weeks, share some of the background of the book — where characters or scenes came from, how they developed, what was left out.

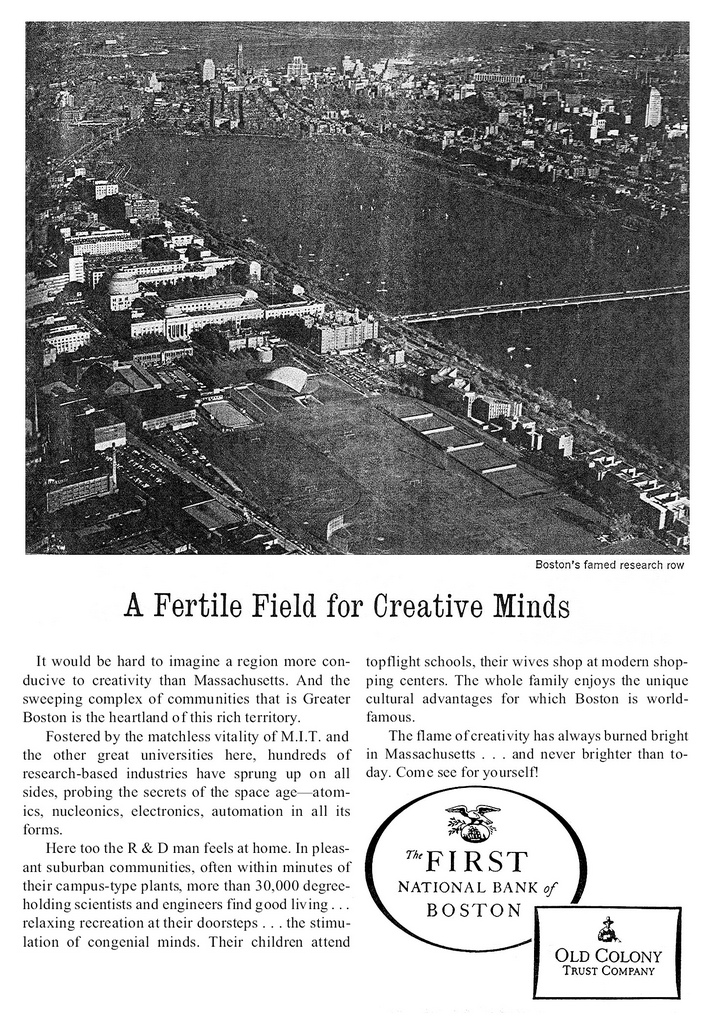

Let’s start with the epigraph. It is ostensibly a quote from a 1962 chamber-of-commerce-type advertisement which begins, “If you haven’t seen the New Boston lately, you’re in for a surprise — America’s city of history is now a city of tomorrow.”

The epigraph establishes the time and place of the story, obviously. The setting is Boston in 1963, an annus horribilis for the city, the year of the Strangler and the Kennedy assassination. Also, the West End — a neighborhood of old tenements and narrow, twisting streets — has recently been demolished to make way for a massive urban renewal project, so the city is physically scarred as well. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is the moment when Boston, a city in a long, steep decline like many other manufacturing centers (Newark, Detroit), began to reinvent itself as the gleaming place you see today.

The epigraph is not authentic. I stitched it together from a few similar ads from the period. I especially liked the one below, which appeared in the November 1962 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. The boosterism in that ad copy, with its jet-age hopefulness, makes a laughable contrast to the grungy reality of city life at the time, particularly in this novel.

Similar ironic devices show up pretty frequently. In the movie “The Full Monty,” the opening credits appear over a promotional film touting the glories of Sheffield, England. A montage of mock period footage is used in the closing credits of “L.A. Confidential” as well. I don’t know, at this point, whether I had “The Full Monty” in mind or not, but “L.A. Confidential,” both the book and the film versions, was an important model for my book.

One last thing: While you’re looking at the ad below, take a look at the image of the city, too. How low the buildings are. On the right, the “old” John Hancock building towers over the Back Bay though it is only 26 stories high. Downtown, at the left center, the 1915 Custom House Tower is still the tallest building at just under 500 feet. This is essentially a nineteenth-century skyline. Boston had seen no major construction in fifty years, a period in which the rest of America’s cities were booming. The Prudential Center in the Back Bay, completed in 1964, was the first modern skyscraper built here. (There is a neat image here of the Back Bay skyline in 1963, with the Pru nearing completion.) This fossilized skyline is a clue. It tells you one reason why the city fathers (no mothers then, sorry) felt so much pressure to see the Strangler murders solved: the “New Boston” had to come. The Strangler case arrived at an inconvenient moment.

Anyway, here is one of the real ads I based my bogus epigraph on. You can see a full-size version here.

Book Three Update

A quick update on my novel in progress. The first draft is roughly half written, and the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. Not only has the book been sold in the U.S. and UK, but we have a new and very enthusiastic publisher in Norway, Versal Forlag. I have had lots of overseas sales, but never in Norway. Takk skal du ha, Versal Forlag. The book continues to be shopped overseas and things are looking quite good, even though at this point all we are showing is a hundred manuscript pages and an outline of the rest. There has even been some movie interest. So, all signs are very positive. In this economy, I am especially thankful for that.

With the business side of things taken care of, I am free to concentrate on the book itself. It is foolish for a writer to talk about an unwritten book, so for now I won’t get into the substance of the plot. Suffice it to say, the manuscript is due on my editor’s desk by April 1, 2010, but I have set a personal deadline of January 1. I have fallen a few weeks behind that schedule, but I am still optimistic I can make up the lost time.

The story, very roughly, is a courtroom drama, with the trial beginning exactly at the midpoint of the book. I think once the trial sequence begins I can write fairly quickly. I am comfortable writing about the courtroom. It is an area I know a little about, having been a prosecutor for several years. The courtroom is also a circumscribed, structured environment. Trials move along in formal, scripted ways, like minuets, with room for just a few dashes of drama and improvisation. No wonder writers are attracted to them. The goal now is to begin that trial sequence September 1. This is how novels are written: not in one leap, but in a series of small, discrete steps. Page by page, scene by scene, one interim deadline after another. The trick is not to look up — you might see how high the mountain above you really is.