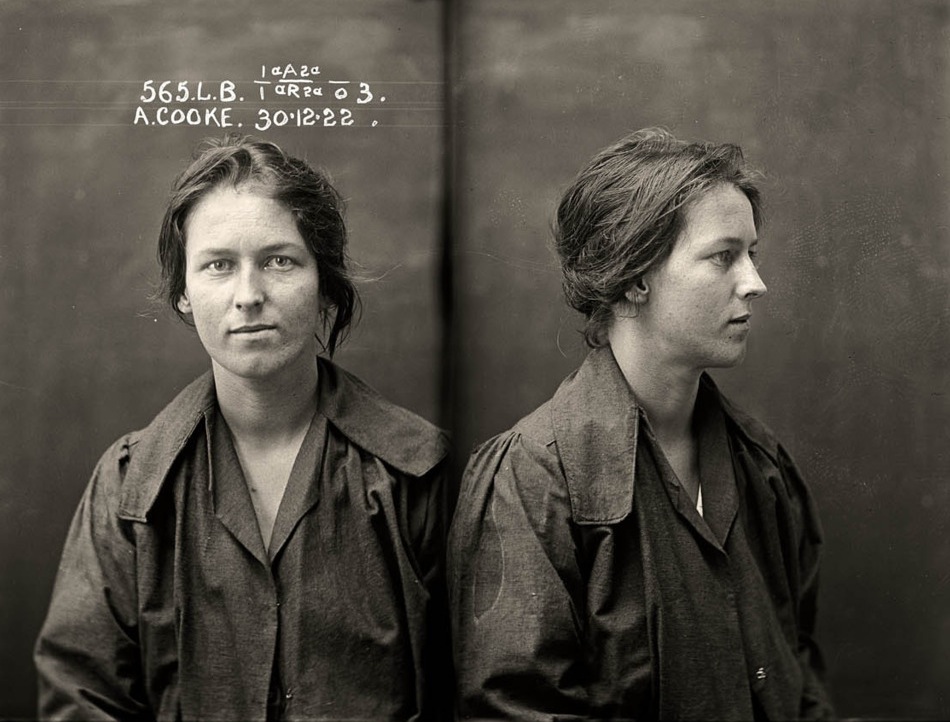

“Alice Adeline Cooke, criminal record number 565LB, 30 December 1922. State Reformatory for Women, Long Bay, New South Wales…. Convicted of bigamy and theft. By the age of 24 Alice Cooke had amassed an impressive number of aliases and at least two husbands. Described by police as ‘rather good looking,’ Cooke was a habitual thief and a convicted bigamist. Aged 24. Part of an archive of forensic photography created by the NSW Police between 1912 and 1964.” Source: Mug Shots of Australian Criminals (via).

Crime

Auden: Murder is unique

Murder is unique in that it abolishes the party it injures, so that society has to take the place of the victim and on his behalf demand atonement or grant forgiveness; it is the one crime in which society has a direct interest.

W.H. Auden, “The Guilty Vicarage” (via)

A Hangman’s Metaphysics

We no longer have any sympathy today with the concept of “free will.” We know only too well what it is — the most infamous of all the arts of the theologian for making mankind “accountable” in his sense of the word, that is to say for making mankind dependent on him…. I give here only the psychology of making men accountable. Everywhere accountability is sought, it is usually the instinct for punishing and judging which seeks it. One has deprived becoming of its innocence if being in this or that state is traced back to will, to intentions, to accountable acts: the doctrine of will has been invented essentially for the purpose of punishment, that is of finding guilty. The whole of the old-style psychology, the psychology of will, has as its precondition the desire of its authors — the priests at the head of the ancient communities — to create for themselves a right to ordain punishments, or their desire to create for God a right to do so…. Men were thought of as “free” so that they could become guilty; consequently, every action had to be thought of as willed, the origin of every action as lying in the consciousness (whereby the most fundamental falsification in psychologicis was made into the very principle of psychology)…. Today, when we have started to move in the reverse direction, when we immoralists especially are trying with all our might to remove the concept of guilt and the concept of punishment from the world and to purge psychology, history, nature, the social institutions, and sanctions of them, there is in our eyes no more radical opposition than that of the theologians, who continue to infect the innocence of becoming with “punishment” and “guilt” by means of the concept of the “moral world order.” Christianity is a hangman’s metaphysics.

— Frederick Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 1889 (via)

The Murder Gene

Last September in Italy, a man convicted of what would, in this country, be called second-degree murder or manslaughter had his 9-year sentence reduced on appeal on the grounds that he exhibited

abnormalities in brain-imaging scans and in five genes that have been linked to violent behaviour — including the gene encoding the neurotransmitter-metabolizing enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA). … Giving his verdict, [the judge] said he had found the MAOA evidence particularly compelling.

The ruling marks the first time a defense based on behavioral genetics — the argument that a defendant’s genes caused him to commit the crime — has affected the outcome of a criminal case in any European court. To my knowledge, no defendant has ever succeeded with this argument in America, either, though many have tried.

I have written before about the implications of behavioral genetics for criminal law, which is built on the assumption that we are generally responsible for our own actions. Surely this is an issue the criminal courts will have to face: some people may indeed be genetically hard-wired for violence. But this decision comes as a surprise to me because the science does not seem to justify it, not yet. We simply don’t know that a single gene like MAOA causes specific behaviors, even in very specific gene-environment interactions. It is a bad decision but a telling one: as the science of behavioral genetics advances, at some point the courts will find it impossible ignore. (To learn more, a great scholarly article by law professor Owen D. Jones is here.)

For now, though, the idea of a “murder gene” is the stuff of novels, not science. My own next novel takes up this very issue. It involves a man named Andy Barber, who descends from a long line of violent men and whose teenage son Jacob is accused of murdering a classmate. Jacob, it turns out, also carries the MAOA gene variant — sometimes called the “warrior gene.” Preparing for his son’s murder trial, Andy says,

The legal question we discussed most … was the relevance of Jacob’s violent bloodline. We referred to this issue as the “murder gene” to express our contempt for the idea, for its backwardness, for the way it warped the real science of DNA and the genetic component of behavior, and overlaid it with the junk science of sleazy lawyers, the cynical science-lite language whose actual purpose was to manipulate juries, to fool them with the sheen of scientific certainty. The murder gene was a lie. It was also a deeply subversive idea. It undercut the whole premise of the criminal law. In court, the thing we punish is the criminal intention — the mens rea, the guilty mind. There is an ancient rule: actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea — “the act does not create guilt unless the mind is also guilty.” This is why we do not convict children, drunks, and schizophrenics: they are incapable of deciding to commit their crimes, not with a true understanding of the significance of their actions. Free will is as important to the law as it is to religion or any other code of morality. We do not punish the leopard for its wildness. But that is the argument Logiudice [the prosecutor] would make if he had the chance: born bad. He would whisper it in the jury’s ear, like a gossip passing a secret. We were determined to stop him, to give Jacob a fair chance.

The murder gene may indeed be junk science, for now at least, but it is a haunting idea. We are quite comfortable with the idea that certain benign traits may inherited — musical talent, athleticism. Why not a talent for violence?

Image: Bryan Christie, “Pharmaceutical Brain”

The issue is inequality, not total wealth

“On almost every index of quality of life, or wellness, or deprivation, there is a gradient showing a strong correlation between a country’s level of economic inequality and its social outcomes. … This has nothing to do with total wealth or even the average per-capita income. America is one of the world’s richest nations, with among the highest figures for income per person, but has the lowest longevity of the developed nations, and a level of violence — murder, in particular — that is off the scale. Of all crimes, those involving violence are most closely related to high levels of inequality — within a country, within states and even within cities.”

— A review in the Guardian of The Spirit Level by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett.

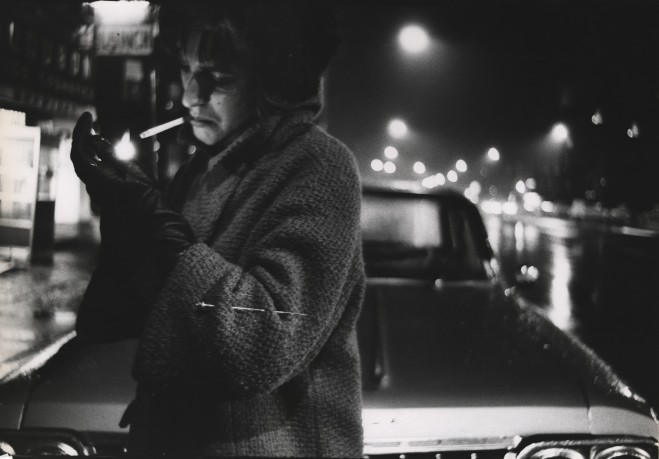

Life Magazine Photos of Boston’s Strangler Days

A trove of remarkable photographs of Boston during the Strangler siege. The photos, which are eerie and beautiful, were taken by Arthur Rickerby for Life Magazine. View the whole collection here. Above: A woman wears a hatpin in her sleeve to defend herself against the Strangler, 1963. (Another here.)

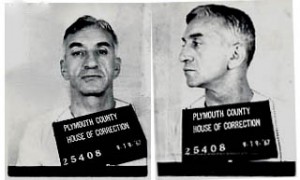

Angiulo, Barboza and fictionalizing the Boston Mob

The animating idea of The Strangler was to recreate Strangler-era Boston, to bring the lost city to life so convincingly that readers would have the immersive three-dimensional experience of actually being there, walking the streets, brushing shoulders with the people. Period authenticity was important: the original working title of the book was The Year of the Strangler.

Of course reanimating the actual city required that a few prominent Bostonians appear undisguised, or nearly so, including gangsters, cops, and politicians. In the original draft, these characters were accurately named and described. The mob boss Capobianco, for example, was called by his real name, Gennaro Angiulo. The historical Gerry Angiulo ran the Boston mob during my childhood in the 1970s. In 1963 and ’64, when The Strangler takes place, he was just consolidating his power.

On the eve of the book’s publication, I got a call from a lawyer at Random House asking about some of these historical figures, including Angiulo. “Is he still alive?” the lawyer wanted to know. Apparently libel laws are stricter when the subject is living. Angiulo was 87 years old then, but still alive in a federal prison. So his name had to be changed. To further insulate the book from a libel charge, Angiulo had to be mentioned by name in the book so we could plausibly deny that my character Capobianco was an Angiulo stand-in. After all, we could argue, there is Angiulo standing next to Capobianco — how could they be the same person? All this sensitivity about the man’s reputation seemed a little ridiculous to me. How was it possible to libel a murderer and convicted mafioso like Gerry Angiulo? But I did not insist, and shortly before publication the character was rechristened Charlie Capobianco. Still the facts remain: the novel’s description of a “born bookie” who became a mob boss — his physical appearance, his biography, his North End headquarters, his bookmaking operation — all are meticulously faithful to the life of Gerry Angiulo. (The libel issue is moot now. Gerry Angiulo died at the end of August, at age 90. His funeral procession required a flatbed truck to carry the 190 bouquets of flowers.)

[Read more…] about Angiulo, Barboza and fictionalizing the Boston Mob

Biocriminology

“There’s certainly a brain basis to crime … the brains of violent criminals are physically and functionally different from the rest of us.”

— Adrian Raine

A burgeoning science suggests that crime is caused in part by biological factors, that is, by traits inherited through DNA or by the brain malfunctioning in very specific ways. Adrian Raine, a “neurocriminologist” and chair of the criminology department at the University of Pennsylvania, says,

“Seventy-five percent of us have had homicidal thoughts. What stops most of us from acting out these feelings is the prefrontal cortex…. When the prefrontal cortex is not functioning too well, maybe an individual, when angry, is more likely to pick up a knife and stab someone or pick up a gun.”

Some criminals, it seems, are biologically different from us.

“People who are psychopaths or who have antisocial personality disorder are literally cold-blooded. They have lower heart rates. When they’re stressed, they don’t sweat as much as the rest of us. They don’t have this anticipatory fear that the rest of us have.”

Obviously I am not qualified to judge the science. But if it is true, as seems increasingly likely, that “freedom of will is not as free as you think,” as Professor Raine puts it, that fact would undercut the entire philosophy of our criminal law, which is that we punish the guilty mind, the mens rea — the conscious, purposeful decision to commit a crime. Where the defendant’s free will or judgment is compromised, because he is drunk or insane or a child, for example, generally the law attaches a lesser degree of culpability, sometimes no culpability at all (the proper finding for an insane defendant is “not guilty by reason of insanity,” not “guilty but insane”).

My third novel, to be published in February 2012, turns on just these sorts of questions. The story involves a father whose teenage son is accused of a murder, a crime that may have been triggered by the boy’s genetic inheritance — a “murder gene.” How should we think of such a criminal? It is not simply a question about crime or criminal law. It is the fundamental subject of crime novels, it is the reason we read them, to ask: What does crime tell us about ourselves and our nature? Modern neuroscience and genetics are beginning to provide answers Dostoyevsky could never have imagined.

Here is Professor Raine on the legal and ethical implications of neurocriminology: