Crime

The road to ruin

If once a man indulges himself in murder, very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking; and from that to incivility and procrastination.

Thomas de Quincey

The Whitey Bulger book I’d like to read

So Whitey Bulger has been caught, and Boston’s greatest crime story will finally have its denouement. Not climax; we’re long past that. But we’re into the last few pages: a few courtroom scenes, a few loose ends to tie up, then we can close the book. (If you need a crash course on the case, start with these articles by George V. Higgins and Alan Dershowitz.)

But why wait for the ending? Already we seem to have decided how the story will be told: Whitey Bulger will go down as an arch gangster, and his signature achievement will be playing the FBI for fools. That was the story told memorably in Black Mass, the nonfiction account by reporters Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill. The theme of informants-run-amok was revisited in “The Departed,” where Jack Nicholson played a gangster “inspired by” Whitey, though Nicholson’s performance was so ridiculous, the rest of the country must have wondered what the hell we Bostonians were so scared of. A second movie is already in the works, this time about Bulger’s murderous Winter Hill Gang, based on a book by its chief thug, John Martorano. We’ll have to wait and see of course, but I’m guessing it’ll be more hard-boiled mobster stuff. John Martorano isn’t exactly the man to write a sensitive, nuanced portrait of his old boss.

I don’t object to any of this. Reducing the story to the familiar shape of a gangster flick is fine, as far as it goes. I love gangster stories as much as anyone. I do have reservations about mythologizing a killer like Whitey, who was exceptionally sadistic even by the standards of his profession. But then, vicious mobsters have inspired great fiction before. Al Capone gave us “Scarface” and “The Untouchables.” Dutch Schultz begat E.L. Doctorow’s Billy Bathgate, one of the best “literary” crime novels I’ve ever read. New York’s Five Families provided the raw material for The Godfather. These are romanticized versions of the truth, of course, and Whitey will have to be romanticized too, for dramatic reasons. But no one is naive enough to believe that these fictions are intended as accurate portraits. So if writers want to retell Whitey’s story as if it was just another gangster movie — “Scarface” or “Goodfellas” with a Boston accent — I say, more power to ’em. Lord knows, I’ve written similar stuff.

But I hope someone will also step forward to write the real story of Whitey Bulger in the full context of his time and place. Which is to say, I hope someone will write the truth. The story is much more complex than Bulger’s manipulation of his FBI handlers. It sprawls over the whole city of Boston. The Bulger book I want to read might be “literary true crime,” like In Cold Blood or The Executioner’s Song, or it may be straight literary historical fiction like Doctorow’s Ragtime or Billy Bathgate. Best of all, perhaps it would be a fictionalized biography, like Colum McCann’s wonderful Dancer or Colm Toibin’s The Master, the sort of book that brings the real man to life. Whatever the style, the book would be big and baggy and discursive enough to tell the whole story.

The lost Vermeer

“The Concert is a painting of c. 1664 by Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. It was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in March 1990. It is considered the most valuable painting currently stolen. Its value has been estimated at over $200,000,000. It remains missing to this day.” — Wikipedia

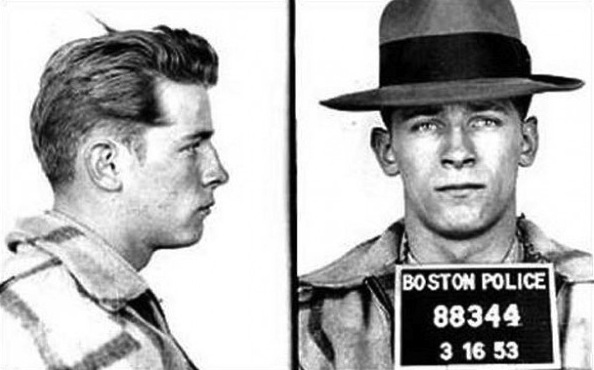

Whitey Bulger, age 23

Southie reacts to the capture of Whitey Bulger

Our golden age

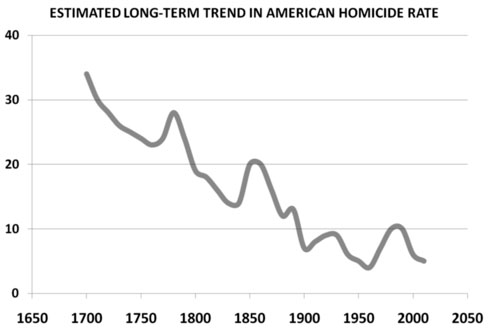

The U.S. murder rate (homicides per 1,000 people) over time. Contrary to popular perception, ours is among the safest eras in U.S. history. Via Andrew Sullivan.

Why are we attracted to crime stories?

Why do ordinary readers happily devour crime novels, the sort of stories I write, about violence — murder above all — and every conceivable sort of treachery? Why do housewives and business travelers and grandmothers — people who would not themselves steal a stick of gum — feel drawn to crime stories, fascinated by them?

John le Carré seems to have puzzled over the appeal of spy novels in a similar way. The other day I ran across this quote:

Most of us live in a condition of secrecy: secret desires, secret appetites, secret hatreds, and relationship with the institutions which is extremely intense and uncomfortable. These are, to me, a part of the ordinary human condition. So I don’t think I’m writing about abnormal things.… Artists, in my experience, have very little center. They fake. They are not the real thing. They are spies. I am no exception.

I think le Carré gets that exactly right. We are all spies. We all fake, one way or another, at times. Spies perfectly embody this aspect of human nature.

Are we all criminals, too? Is that why we rush to buy books by Lee Child or Richard Price or Michael Connelly? Is that why the news media cover crime stories with such obvious relish?

Maybe. When asked to explain the attraction of crime stories, I have always fallen back on the phrase “bad men do what good men dream,” which was coined by the psychologist Robert I. Simon (it is the title of Simon’s book). Simon writes,

The basic difference between what are socially considered to be bad and good people is not one of kind, but one of degree, and of the ability of the bad to translate dark impulses into dark actions. Bad men such as serial sexual killers have intense, compulsive, sadistic fantasies that few good men have, but we all have some measure of that hostility, aggression, and sadism. Anyone can become violent, even murderous, under certain circumstances. Our brains are wired for aggression, and can short-circuit into violence.

It is a powerful, frightening idea. But even if it is true — even if we are all criminals with secret dark instincts, however faintly we feel them, however well we master them — it still does not explain the precise nature of our attraction to crime stories. When we read crime novels, are we indulging this secret urge to violence, acting out fantasies? Are we good men (people) dreaming of doing bad things? Our favorite criminals — Hannibal Lecter, Michael Corleone — do have an undeniable glamor.

On the other hand, maybe we read crime stories to relieve the anxiety that we will become victims. Maybe the pleasure is in the experience of control over these demons. Most crime stories end with the villain’s defeat, after all. Justice tends to triumph in fiction more often than it does in real life. Surely that is no accident.

Or perhaps we enjoy crime stories for the same reason we go to horror movies and roller coasters: to feel the thrill of fear. To get the adrenaline rush of a dangerous situation without the risk of actual danger.

I suspect that the precise nature of our attraction to crime stories is murkier than le Carré’s theory about spy novels. We may indeed all be spies, but we are not all criminals — not just criminals, anyway. We are good and bad, cops and robbers, heroes and villains, at different times. As a crime novelist, that strikes me as good news. Novels thrive in the murk of human emotions.