I am always doing what I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it.

Pablo Picasso (via)

Official website of the author

I am always doing what I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it.

Pablo Picasso (via)

You may not be a Picasso or Mozart but you don’t have to be. Just create to create. Create to remind yourself you’re still alive. Make stuff to inspire others to make something too. Create to learn a bit more about yourself.

Paul Simon performs a partially written “Still Crazy After All These Years” in September 1974: “I’ve been stumped here for a while.” I know the feeling.

We think the Mac will sell zillions, but we didn’t build the Mac for anybody else. We built it for ourselves. We were the group of people who were going to judge whether it was great or not. We weren’t going to go out and do market research. We just wanted to build the best thing we could build.

When you’re a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you’re not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.

Steve Jobs, 1985 (via)

I was heartened (relieved, really) to find this wonderful essay describing Leonardo da Vinci as “a hopeless procrastinator.”

Leonardo rarely completed any of the great projects that he sketched in his notebooks. His groundbreaking research in human anatomy resulted in no publications — at least not in his lifetime. Not only did Leonardo fail to realize his potential as an engineer and a scientist, but he also spent his career hounded by creditors to whom he owed paintings and sculptures for which he had accepted payment but — for some reason — could not deliver, even when his deadline was extended by years. His surviving paintings amount to no more than 20, and five or six, including the “Mona Lisa,” were still in his possession when he died. Apparently, he was still tinkering with them.

Nowadays, Leonardo might have been hired by a top research university, but it seems likely that he would have been denied tenure. He had lots of notes but relatively little to put in his portfolio.

What makes the essay so interesting is the suggestion that Leonardo’s epic procrastination, far from being a character flaw or an impediment, was the very key to his creativity. So many of the things for which we celebrate Leonardo are the product of his procrastination, especially the notebooks which overflow with ideas and visions, daydreams about helicopters and double-hulled ships and so on. Leonardo’s notebooks are the primary reason we think of him as a genius, the archetypal polymath Renaissance man, rather than “just” a brilliant artist. And he was paid for none of that creative work. It is what he did when he ought to have been doing something else.

Would he have achieved more if his focus had been narrower and more rigorously professional? Perhaps he might have completed more statues and altarpieces. He might have made more money. His contemporaries, such as Michelangelo, would have had fewer grounds for mocking him as an impractical eccentric. But we might not remember him now any more than we normally recall the more punctual work of dozens of other Florentine artists of his generation.

I don’t want to get carried away. The lesson of Leonardo’s life is not to abandon yourself to procrastination. Procrastination has to be controlled. There is work to do, bills to pay. I get that.

At the same time, it is useful — for artists, especially — to think of procrastination not as a vice or a personal weakness, but as a signal, an alarm bell. It is the clearest possible indication that your current project is not inspiring to you. After all, you don’t put off something you enjoy doing. Your mind does not wander if it is engaged in something interesting.

The usual advice to procrastinators who yearn to be “cured” is to exert ever more discipline and hard work. Manage the problem. Put systems in place to help you complete a project that bores you to tears. Those are useful strategies, sometimes. Boring work simply has to get done, sometimes. But maybe, sometimes at least, we are looking in the wrong place. Maybe the problem is not the worker, but the work. Remember, it is the writer’s job never to be boring, and if a project is boring to the writer himself…

Every writer knows the self-lacerating guilt that accompanies unproductive days. Lately, I have been grinding away on a stalled, lifeless book. I have spent weeks on technical problems: trying to piece together the story or engineer characters to fill various plot functions. Or simply struggling to find new ideas worth writing about. It is an inefficient, unproductive, maddening part of the process. And of course I have bashed myself endlessly for procrastinating, for all the lost hours.

But maybe I ought to be asking not what’s wrong with me, but what’s wrong with this novel? Why doesn’t it inspire me? Or, more usefully, how can I turn it into the sort of novel that will inspire me? Every writer, every artist, of even moderate ambition wants to work with passion, on projects that fill him with a sense of mission. If the project before you does not do that, then change it till it does.

For a lot of writers, I admit, that is terrible advice. Certainly it contradicts the received wisdom. When wise old writers pontificate about How To Write, one chestnut they always toss off is “Don’t wait for inspiration.” And it is true that there are plenty of writers out there who work whether they are inspired or not. They churn out a book a year, steady, workmanlike, professional, unsurprising, consistent, well-crafted books. I admire them. I envy them, honestly. You should emulate them if you can.

But I don’t want to work that way and I don’t want to write books like that. I want every book to be the best fucking thing I’ve ever done. I want every book to be electric — a mission, not just a paycheck. I want to work at the absolute outer limit of my talent, always. That sounds naive and grandiose, I know, but there it is.

We writers always complain about modern readers. “They have lost their ability to focus deeply. The web has ruined them. They read like rabbits, skittish, hopping here and there. They don’t have the necessary attention span for novels. Novels are dying because of them.” We ought to remember that when we procrastinate, when we feel uninspired, our own mood — distracted, disengaged, dull, sniffing about for something interesting — is very much like the resting state of our audience. It is our job to make novels so intensely interesting that rabbity modern readers will feel they have to read them. They will close their laptops, turn off their ginormous high-def TVs, and pick up a book instead. The surest way to do that is to choose projects that are so intensely interesting to ourselves that we feel the same sort of compulsion to close our web browsers and get to work.

Procrastination is not always bad. It may be a signal. If you consistently feel you’d rather be doing something else, then your project is obviously lacking something. Don’t ignore that signal. Use it.

(Now go read that essay on Leonardo.)

As I read about how creativity works, an idea keeps recurring:

Groundbreaking innovators generate and execute far more ideas. Research has shown that the single strongest correlation to innovative success — any category, anywhere, artists, scientists, entrepreneurs, policymakers, musicians — is the number of ideas they came up with and tried to make happen.… The reason why we see this relationship is because of a fundamental flaw in humans when it comes to creative and innovative ideas, which is: we are not particularly good at predicting what’s going to work or not work.

I stumbled across that quote in a talk by Frans Johansson (at around 5:45 of the video). It echoed a similar striking quote from Robert Sutton, which I mentioned a few weeks ago.

Renowned geniuses like Picasso, da Vinci, and physicist Richard Feynman didn’t succeed at a higher rate than their peers. They simply produced more, which meant that they had far more successes and failures than their unheralded colleagues. In every occupation … from composers, artists, and poets to inventors and scientists, the story is the same: Creativity is a function of the quantity of work produced.

I was so struck by this idea, I decided to quickly check out the evidence.

Those are outlandish numbers, obviously, from a cherry-picked list of the famously prolific. What happens when we ignore the obvious, certified geniuses? What if we look at a few of the modern novelists I admire most? Well, they are all prolific, too.

No, it’s not the most scientific study. And there is some selection bias there: one of the reasons I admire these writers in the first place is that they have been so productive for so long. But it is hard to dispute Sutton’s conclusion: Creativity is a function of the quantity of work produced.

Lesson #1: Churn it out. Writers like Harper Lee — the one- or two-book writers who achieve great things — are a tiny minority. The surest way to create great work is to create a lot of work. Do not wait for the Big Idea; even if you had it, you would not recognize it. Execute a lot of ideas, even the imperfect ones. Trust that somewhere in that body of work will be the one or two transcendent achievements you are hoping for.

Lesson #2: Embrace failure. It is part of the creative process. You cannot succeed without failing — and failing a lot. No matter. As Beckett said, “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

For a procrastinator and perfectionist like me, those are two vital points to remember.

* 20,542 is just the number of Picasso’s works that have been confirmed and cataloged thus far. Estimates of all work produced range as high as 50,000.

** Famously prolific, Dickens’ total output is hard to quantify. Some line-drawing is necessary. I’ve counted as “major works” the 20 novels, 4 short story collections, 17 Christmas numbers of the magazines Dickens edited and contributed to, and 9 collections of nonfiction, poetry, and plays. (The list I used is here.) It is a rough but conservative estimate since it omits the deluge of shorter pieces he wrote for periodicals, not to mention his myriad other activities.

*** Einstein also published about 150 non-scientific papers, mostly on humanitarian or political subjects.

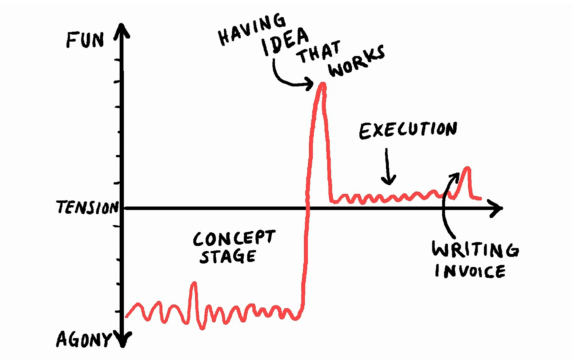

This is a slide from designer/illustrator Christoph Niemann’s charming recent talk at Creative Mornings. Substitute “Sending Manuscript to Editor” for “Writing Invoice,” and you pretty much have the writing life. Watch the whole talk if you have a few minutes. (Via Brain Pickings.) For the record, I am currently mired in the agony of the concept stage … still.