Gorgeous images of New York City by photographer Barbara Mensch. Some background information about Barbara Mensch is here.

Art

Lawrence Lessig on the Google book search settlement

Will Google Books, the audacious attempt to digitize every book ever written, have the perverse effect of making books — and ideas — less available, less ubiquitous, less free? Will copyright laws require that most of the books written in the last century be excluded from the new digital online library? Is this progress? This is Lawrence Lessig speaking at Harvard two weeks ago. Lessig’s presentation runs about 28 minutes followed by a 15-minute Q&A.

Crime novels and entertainments

I was interested to read on Sarah’s blog about the fuss John Banville raised recently. Banville said, undiplomatically, that he writes more quickly and easily as crime writer “Benjamin Black” than he does writing literary novels under his own name. There were hurt feelings, suggestions that Banville was “slumming,” and the author felt compelled to issue a foot-shuffling clarification. “The distinction between good writing and bad,” he said, “is the only one worth making.”

That is so obviously untrue — lots of distinctions beyond good/bad are worth making — that Banville must have held his nose while typing it. The whole thing reminds me of Michael Kinsley’s definition of a Washington gaffe: when a politician inadvertently tells the truth in public.

Does anyone really doubt that an author would find it easier to write freely when he is working in a genre with established conventions? There are plenty of challenges to genre writing, of course. The writer can stick to the conventions, subvert them in various ways, update them, etc. But the rules do exist. The relative difficulty in writing “literary” novels is not that there aren’t models to follow; non-genre writers mimic older stories all the time. The difficulty — at least the one Banville meant — is that storytelling conventions are less clear and less important. The writer is at sea. That is why literary writers like Banville, Richard Price, and E.L. Doctorow (Billy Bathgate) feel relieved when they come to crime writing. Finally, there is a roadmap, a method to plotting the story. As a crime writer, I am thankful for that roadmap every day.

It is also obvious that genre novels place a higher priority on entertaining the reader. This is the umpteenth rehash of Graham Greene’s old distinction between novels and entertainments, and the only remaining mystery is why on earth we continue to worry about it. Listen to Greene (see below) as he briefly discusses the subject. It turns out, the novels/entertainments distinction didn’t hold up very well even for the man who invented it. “Most of my novels have an element of melodrama,” Greene concedes, even the literary ones. All novels need drama, even the melo- kind.

So let’s not be so touchy, crime fans. Entertainments — yes, crime novels included — are indeed easier to write, just as Banville says. They are also generally easier to read, precisely because they take seriously the writer’s duty to entertain. Why apologize for it?

By the way, I always find it a little disconcerting to hear or see an author whose books I love. The authorial voice is one the reader creates in her own head. Greene’s actual, reedy voice is not the one I’d imagined for him. (Click below to hear him.) Yet another example of the internet revealing too much.

[jwplayer config=”Landay Audio Player” file=”/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/05-Novels-And-Entertainments.mp3″ /]

Kate’s Mystery Books closes (for now)

Kate’s Mystery Books in Cambridge closed on Saturday. Kate Mattes held an event with an army of volunteers who helped pack the place up. I stopped by and chatted briefly with Kate, who told me she plans to spend the next year or so getting her enormous inventory properly cataloged online, as well as digitizing two decades worth of book reviews. Then she may look around for a new bricks-and-mortar location if the conditions are right. In the meantime she will continue to hold author events, and her web site is still around.

It goes without saying that the city is a duller place this morning without Kate’s. Of course any number of bookshops have closed the last few years, but this loss feels particularly sad. I never knew the shop especially well, but it seemed like one of those places. It had the patina of years, and a community of readers had sprung up around it. Places like that can’t be replaced or recreated, least of all by a website.

But there’s no use sighing over the blandification of Cambridge, where a funky overstuffed bookstore in an old rambling red Victorian once would have seemed right at home. Or the general extinction of bookstores run by real, live book lovers. Things change. It sucks, but what can you do?

So I will just thank Kate for supporting me from the day my first book arrived and hand-selling my books ever since. I’m sure there is a marching band of writers out there who feel the same way. Thank you, Kate. We’ll see you around.

The Definitive Boston Crime Novel: “The Friends of Eddie Coyle”

Yesterday I wrote about the film version of The Friends of Eddie Coyle, which I think is the best movie ever made about Boston. Today, over at the Rap Sheet, my review/appreciation of the George V. Higgins novel is up, part of the Rap Sheet’s “Book You Have to Read” series highlighting forgotten classics. Here is a clip:

Elmore Leonard, in his introduction to the Holt paperback edition, recalls reading The Friends of Eddie Coyle when it first came out. “I finished the book in one sitting and felt as if I’d been set free. So this was how you do it. … To me it was a revelation.” Leonard has called it “the best crime novel ever written.”

Eddie Coyle was a revelation to me, as well. I was a young assistant D.A. when I first read it, another Boston College Law grad with literary aspirations. I worked in Cambridge then, across the river from Higgins’ old office. I had never read the book. I was only eight when it came out, and later I was never much of a crime-novel fan anyway. But when I hit the first page, I had the same reaction Leonard did: so this is how you do it.

Read the rest here. Of course calling any book or movie the best of its type is a good way to start an argument, but I did it yesterday so why stop now? The Friends of Eddie Coyle is the best crime novel I’ve ever read.

Best Boston Movie Ever: “The Friends of Eddie Coyle”

Recently I wrote a short appreciation for the Rap Sheet of George V. Higgins’s definitive Boston crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The piece will run soon as part of the Rap Sheet’s terrific Friday series, Books You Have to Read, which celebrates forgotten (or never properly appreciated) crime novels. [Update: My article on the novel is now up. You can find it here.]

Fortuitously, Criterion just released a pristine new restoration of the 1973 film version of The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and it is not to be missed. The Criterion DVD brings back a forgotten classic and the best movie about Boston ever.

Let’s be honest: there aren’t that many great movies about Boston, particularly crime stories, though the city has bred more than its share of crime novelists. There are some good movies set in Boston that could as easily take place elsewhere without losing much; The Verdict comes to mind. But movies that aim to capture this city’s unique personality — as, say, L.A. Confidential and Chinatown do for Los Angeles? Or Goodfellas and Once Upon a Time in America are unmistakably New York stories? Those are rare.

The serious competition is all recent. Good Will Hunting is fun but overrated. (Watch it again.) The Departed is just not a serious movie, and anyone who believes Jack Nicholson or Leonardo DiCaprio would last five minutes in Whitey Bulger’s world really ought to turn off the DVD player and come out into the world for a while.

The only real challenger for the title of best Boston movie is Mystic River. But put the two films side by side and Mystic River looks like Eddie Coyle lite — Boston as Californians might imagine it. Mystic River is just too much of everything: a melodrama, pretty to look at, with gorgeous swooping helicopter-cam shots of the city skyline and a platoon of glamorous stars, all of them strenuously, visibly acting. These are the sort of big, emotive performances we now recognize as Oscar bait, Sean Penn’s in particular.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle is the real thing. Quiet and dingy, a series of terse conversations in dim bars and gray, leafless parks. It is an ensemble piece, despite having a big-ticket star in Robert Mitchum. Voices are rarely raised. Only two fatal shots are fired. This is the reality of small-time crime life: not high drama, but a wary, exhausting series of risky transactions dimly understood even by the thick-headed hoods on the inside.

With any Boston movie, we have to consider how the difficult Boston accent is handled, too, and here Mystic River flops badly. I saw it in Boston in a theater full of Bostonians, and the audience seemed to require subtitles to understand what the hell these people were saying. Eddie Coyle has a few wobbly moments but mostly gets it right. Alex Rocco, now remembered mostly as Moe Greene in The Godfather, plays a convincing Boston hoodlum. He should: as a pudgy kid named Bobo Petricone he hung around on the periphery of the fearsome Winter Hill Gang.

Eddie Coyle is not perfect by any means. A lot of the dialogue is lifted straight from the novel (that Higgins did not get a screenwriter credit is a travesty), and some of those lines don’t work as well in the actors’ mouths as they do on the page. And the seventies tics — the wah-wah soundtrack, the groovy idioms, “man” and “lover” and so on — can be a bit much, though you might go in for that sort of thing.

It may be, too, that the film appeals to me as a time capsule of a city I remember. To a kid who grew up in Boston, it is a kick to see Barbo’s furniture store. (Any New Englander of a certain age can sing the Barbo’s jingle, which played on car radios incessantly.) And to revisit the old Boston Garden, where Eddie watches the sports god of my childhood, “number four, Bobby Orr — what a future he has.” Just seeing Boston in late fall — completely drained of color, the trees all bare, the grayed-out sunless sky, the people dressed in drab — is enough to make me feel poignant and murderous.

But the main thing The Friends of Eddie Coyle has going for it is Mitchum, speaking the incomparable lines of George Higgins. Mitchum is not the Eddie Coyle of the book. Even in his brokedown fifties, Mitchum is too big and handsome for that. He can’t smother his leading-man charisma enough to quite become a small-time loser like Eddie. So this Eddie Coyle is Mitchum’s own creation. The booklet that accompanies the new Criterion DVD — which alone is worth the price of the disk — says that Mitchum was first offered the part of Dillon, the two-faced bartender. That part instead went to a then-unknown Peter Boyle. Good thing. Mitchum gives the the best performance of his life. He is as quiet and understated as Sean Penn is actorly. There is not a hint of the preening movie star anywhere in his performance. Watch this clip and notice how little Mitchum moves his body or alters his expression, how he communicates a lot while “signaling” very little. The effect is completely convincing. That voice, that smirking wised-up manner — true Boston.

E-Books and Distracted Reading

Author Steven Johnson on what we may be losing in the switch to e-books.

Because they have been largely walled off from the world of hypertext, print books have remained a kind of game preserve for the endangered species of linear, deep-focus reading. Online, you can click happily from blog post to email thread to online New Yorker article — sampling, commenting and forwarding as you go. But when you sit down with an old-fashioned book in your hand, the medium works naturally against such distractions; it compels you to follow the thread, to stay engaged with a single narrative or argument.

The Kindle in its current incarnation maintains some of that emphasis on linear focus; it has no dedicated client for email or texting, and its Web browser is buried in a subfolder for “experimental” projects. But Amazon has already released a version of the Kindle software for reading its e-books on an iPhone, which is much more conducive to all manner of distraction. No doubt future iterations of the Kindle and other e-book readers will make it just as easy to jump online to check your 401(k) performance as it is now to buy a copy of On Beauty.

As a result, I fear that one of the great joys of book reading — the total immersion in another world, or in the world of the author’s ideas — will be compromised. We all may read books the way we increasingly read magazines and newspapers: a little bit here, a little bit there.

(Read the whole thing here.)

The internet is a near-perfect publishing medium, both a copy machine and “super-distribution system.” At the same time, it creates an attention deficit: accustomed to “surfing” and “browsing,” we can barely hang on long enough to read a short blog post, never mind the deep dive of a whole book. The internet promises to bring us the bounty of every book ever written delivered instantly at the click of a link — even as it trains us not to want them.

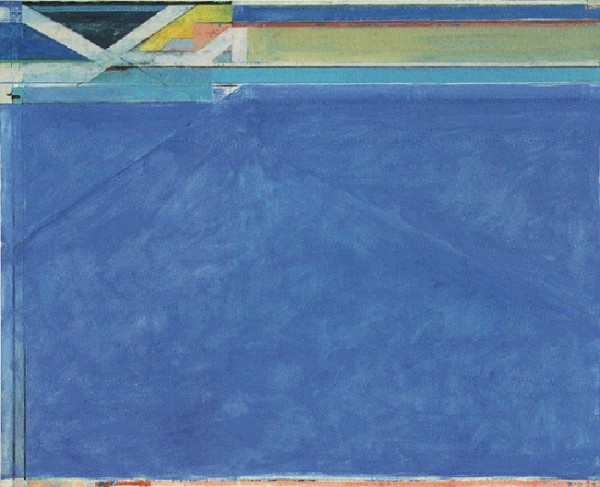

Richard Diebenkorn: Notes to Myself on Beginning a Painting

The following list was found among the papers of the painter Richard Diebenkorn after his death in 1993. Spelling and capitalization are as in the original. (Via Terry Teachout.)

Notes to myself on beginning a painting

- attempt what is not certain. Certainty may or may not come later. It may then be a valuable delusion.

- The pretty, initial position which falls short of completeness is not to be valued — except as a stimulus for further moves.

- Do search. But in order to find other than what is searched for.

- Use and respond to the initial fresh qualities but consider them absolutely expendable.

- Dont “discover” a subject — of any kind.

- Somehow don’t be bored — but if you must, use it in action. Use its destructive potential.

- Mistakes can’t be erased but they move you from your present position.

- Keep thinking about Polyanna.

- Tolerate chaos.

- Be careful only in a perverse way.

Image: Richard Diebenkorn’s painting Ocean Park No. 129, 1984.