Art

“Next” by James Hynes

I do not review many novels on this blog. I do not like to criticize authors. I know all too well how difficult it is to write a novel. I know the author’s anxiety — as David Remnick has described it,

the sense of dread, a self-lacerating concession that the book is not so much finished as abandoned and that positively everyone will see all the holes that are surely there, all the illogic, the shortcuts, the tape, the glue.

To point these things out — the tape, the glue, the flaws — feels a little cruel to me. And unnecessary, since we have no shortage of self-appointed book critics armed with blogs and Twitter feeds and what-all. So generally, when it comes to reviewing one another’s work, I think we writers ought to do as our mothers told us: “if you can’t say something nice…” At the same time, I do see flaws in most every book I read, if only small ones. I can’t help it; I’ve been doing this awhile myself. So what can I say? Nothing, usually. That is why I don’t mention most of the books I read.

There is another problem, too. You are as apt to make a fool of yourself raving about a book as trashing it. In my experience, the euphoria of finishing a novel that feels special usually sours pretty quickly. I tend to ruminate about things, and if you think about any novel long enough, if you flyspeck it and worry it and turn it over and over, then yes, inevitably you will find flaws. You can talk yourself out of loving anything. It’s not just books, either. Very often the things I fall in love with — the band that sounded so cool when I first heard it on the radio, the movie I raved about as I walked out of the theater, the woman who looked so beautiful at first glance (yeah, yeah, back when I was single) — all these things tend to lose their magic as I think about them. And think about them and think about them… So I have learned not to trust my first instincts when I love a book. Wait a couple of days, I tell myself. Let it cool.

The net result of all this overthinking is that, when I do truly love a book, I hesitate to say so.

I am feeling that sort of hesitancy now, because what I want to say, honestly, is that the book I just finished — Next by James Hynes — is one of the best novels I have ever read. Over the next few days, I’m sure I will begin to hedge. I will wish I was more temperate in what I wrote here. But right now, with the last few paragraphs still ringing in my ears? I can’t think of a novel I have enjoyed as much or been as deeply moved by. Certainly it’s been a long, long time since I had an electric reading experience like the last twenty or thirty pages of this book.

Next

It’s a good thing, too, because the entire novel is spent inside Kevin’s head. The book traces Kevin’s every wandering thought, every memory, every insight as he aimlessly slopes about Austin on a sultry morning. Imagine Mrs. Dalloway retold by Nicholson Baker and you’re in the right ballpark.

The prose is inventive and precise. Observing a line of planes parked at an airport terminal, Kevin sees “an accordion jetway affixed to each plane like a remora to a shark.” Open any page and you’ll find a wonderful line like that. Hynes is just a terrific sentence-writer.

If that’s all Next was — a skillful mashup of Virginia Woolf, Nicholson Baker and (say) Nick Hornby — it would be satisfying enough. But it would not be special. Not this special. It is impossible to say more without spoiling the book for you. Suffice it to say, the climax of the book is just about the best I’ve ever read.

Will I still think so when I’ve recovered from the experience of those last twenty or thirty pages? In a week or a month, will I still think Next is one of my favorite books ever? I don’t know. Maybe not. The book is utterly unpretentious. It does not have any of those very solemn passages that purport to tell you The Way Things Are, as certifiable Great Books are supposed to have. It will be an easy book to discount. But judging it by the way I felt when I turned the last page and closed the book? Yes. I felt, as Emily Dickinson put it, “physically as if the top of my head were taken off.” Well, that isn’t quite right. When I closed Next, a few hours ago now, the feeling was not as if the top of my own head were taken off, but as if the top of Kevin Quinn’s was (figuratively) opened up to me. I felt as if I had lived another man’s life for a while and came away with a greater appreciation of my own.

Drawing Circles

The other day I blogged about the story of Giotto’s O: A messenger from the Pope arrived in Giotto’s studio in Florence one morning. He asked for a drawing to prove the artist’s skill to the Pope, who was seeking a painter for some frescoes in St. Peter’s. As Vasari tells the story, Giotto “immediately took a sheet of paper, and with a pen dipped in red, fixing his arm firmly against his side to make a compass of it, with a turn of his hand he made a circle so perfect that it was a marvel to see it.” Of course, Giotto got the job.

I had never heard the story until I ran across it online recently. It stuck in my mind, a romantic parable of what artistic mastery means. To paint an angel, first you must learn to paint a perfect circle — something like that.

Curious, I wandered around the web looking for more information about Giotto and his circle, and, in the hopscotch way of the web, I found an interesting blog post that linked Giotto’s O to a different sort of circle, the ensō, the asymmetric circle of Japanese Zen calligraphy.

In Zen Buddhist painting, ensō symbolizes a moment when the mind is free to simply let the body/spirit create. The brushed ink of the circle is usually done on silk or rice paper in one movement (but the great Bankei used two strokes sometimes) and there is no possibility of modification: it shows the expressive movement of the spirit at that time. [Wikipedia]

The imperfection of the circle — the asymmetry, the visible brush trails, the blobs of ink — is the point. In its very “flaws,” ensō embodies a traditional Japanese aesthetic, fukinsei (不均整), asymmetry or irregularity. Garr Reynolds (one of my favorite bloggers) explains,

The idea of controlling balance in a composition via irregularity and asymmetry is a central tenet of the Zen aesthetic. The enso … is often drawn as an incomplete circle, symbolizing the imperfection that is part of existence.

So these two famous circles, Giotto’s O and the ensō, embody very different aesthetic ideals.

Giotto’s circle is precise mechanical perfection, “a circle so perfect that it was a marvel to see.” Even his technique is machinelike: he pins his elbow to his side, turning his arm into a virtual compass.

Vasari adds another detail, as well. In the versions of the story that I initially read, Giotto loads his brush with red paint and paints the circle with a single sweep of his arm. But in Vasari’s telling, Giotto scratches out his circle with a pen (a quill, presumably) rather than a brush. He wants to eliminate even the wavering edge of a brush stroke, the little quivers of the bent bristles.

In writing, that sort of perfectionism is fatal. The very idea of creating “perfect” sentences or stories is paralyzing. No one can write perfectly. I have learned this lesson the hard way. I am a perfectionist by nature. It is no wonder the Giotto story appealed to me. But there are no Giottos in writing. You have to embrace imperfection, you have to accept the little oddities and surprises that emerge in the moment of creation, in the immersive “flow” state that characterizes the best writing sessions. I don’t know the first thing about Zen, but to me the go-with-it philosophy of the ensō feels much truer to the actual experience of writing well. It is not a feeling of abandon; like ensō painting, good writing is never careless or out of control. At the same time, every writer has to accept the little wobbles of his brush, the little traces of his bristles, the funny pear-shape of his ensō. Not because these flaws are unavoidable (though they are) but because they are beautiful.

To a writer like me — who tends to self-edit too much, who sometimes imagines he can write perfectly — the story of Giotto’s O teaches the wrong lesson. I will think of the ensō instead.

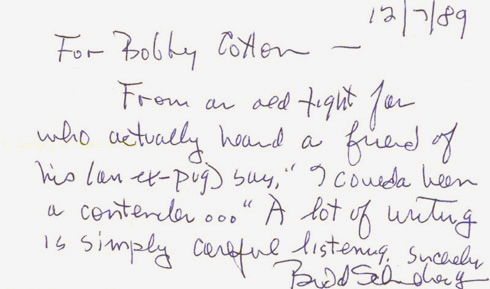

The origin of “I coulda been a contender”

A note from screenwriter Budd Schulberg to a fan, jotted on the back of an index card, explains the origin of the famous line from “On the Waterfront.” The note reads:

12/7/89

For Bobby Cotton —

From an old fight fan who actually heard a friend of his (an ex-pug) say, “I coulda been a contender…” A lot of writing is simply careful listening.

Sincerely,

Budd Schulberg

Now, about that one-way ticket to Palookaville…

Diego Velázquez: Las Meninas

Giotto’s Red Circle

Pope Boniface VIII was looking for a new artist to work on the frescoes in St. Peter’s Basilica, so he sent a courtier out into the country to interview artists and collect samples of their work that he could judge. The courtier approached the painter Giotto and asked for a drawing to demonstrate his skill. Instead of a study of angels and saints, which the courtier expected, Giotto took a brush loaded with red paint and drew a perfect circle. The courtier was furious, thinking he had been made a fool of; nonetheless, he took the drawing back to Boniface. The Pope understood the significance of the red circle, and Giotto got the job.

The story of Giotto’s O apparently dates from Vasari’s Lives of the Painters. First published in 1550, more than two centuries after Giotto’s death in 1337, Vasari’s profile adds this nice coda to the story:

This thing being told, there arose from it a proverb which is still used about men of coarse clay, “You are rounder than the O of Giotto,” which proverb is not only good because of the occasion from which it sprang, but also still more for its significance, which consists in its ambiguity, tondo, “round,” meaning in Tuscany not only a perfect circle, but also slowness and heaviness of mind.

Like being called “thick as a brick” today.

What makes Emma Bovary so interesting?

Sometimes in reading at random, weird patterns emerge. The last couple of days I ran across these two quotes, both trashing sacred-cow novelists. In the first, from The Paris Review in 1963, Katherine Anne Porter explains why she detests F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Not only didn’t I like [Fitzgerald’s] writing, but I didn’t like the people he wrote about. I thought they weren’t worth thinking about, and I still think so. It seems to me that your human beings have to have some kind of meaning. I just can’t be interested in those perfectly stupid meaningless lives.

The next is from B.R. Myers’ acid review of Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Freedom, in The Atlantic:

One opens a new novel and is promptly introduced to some dull minor characters. Tiring of them, one skims ahead to meet the leads, only to realize: those minor characters are the leads. A common experience for even the occasional reader of contemporary fiction, it never fails to make the heart sink. The problem is not only one of craft or execution. Characters are now conceived as if the whole point of literature were to create plausible likenesses of the folks next door. They have their little worries, but so what? Do writers really believe that every unhappy family is special? … Granted, nonentities are people too, and a good storyteller can interest us in just about anybody, as Madame Bovary demonstrates. But … whatever is wrong with these people [i.e. the characters in Freedom] does not matter.

I won’t get into the mean-spiritedness of these reviews, except to say that they capture why I could never be a book critic. (I do post book reviews on this blog, but never negative ones. If I can’t recommend a book, I simply don’t mention it.) And I’m not especially interested in the merits of these opinions, either, though Porter’s dismissal of Fitzgerald seems asinine to me. (I haven’t read Freedom.)

But they do raise an interesting question: what makes an insipid character worth writing and reading about? Obviously it is not as simple as “dull characters, dull book,” as Myers’ example of Madame Bovary makes clear. (My choice would have been Mrs. Dalloway). Is it only the skill of the novelist that grants significance to minor lives? Or do the shallow protagonists of successful books share common characteristics — are they shallow in some distinctive, dramatically advantageous way? If it had been Flaubert rather than Franzen writing about ordinary folks in Minnesota, would it have made a difference to readers like B.R. Myers, who evidently feels the whole project was doomed from the start merely by Franzen’s choice of subject?

“Strawberries” by Edwin Morgan

There were never strawberries

let the sun beat

let the storm wash the plates

(Hat tip: My friend Michael Malone blogged this poem upon Edwin Morgan’s death a few weeks ago. More about Morgan here.)