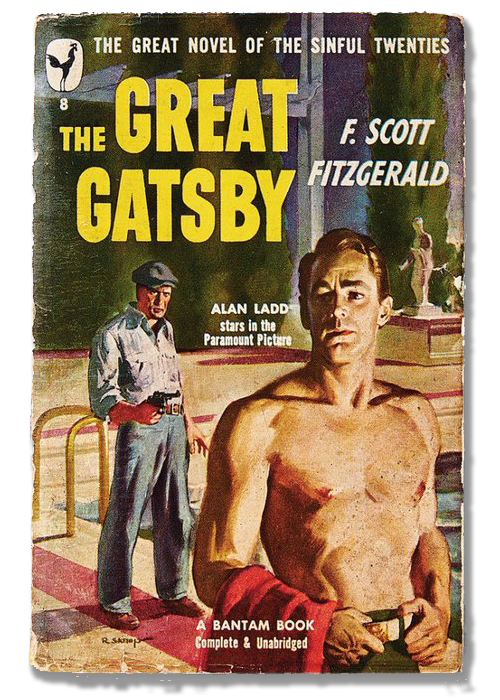

A paperback tie-in version for the 1949 movie featuring Alan Ladd. Not exactly how I pictured Gatsby, but there’s no accounting for taste.

Official website of the author

A paperback tie-in version for the 1949 movie featuring Alan Ladd. Not exactly how I pictured Gatsby, but there’s no accounting for taste.

I am riding on a limited express, one of the crack trains of the nation.

Hurtling across the prairie into blue haze and dark air go fifteen all-steel coaches holding a thousand people.

(All the coaches shall be scrap and rust and all the men and women laughing in the diners and sleepers shall pass to ashes.)

I ask a man in the smoker where he is going and he answers: “Omaha.”

From Chicago Poems (1916)

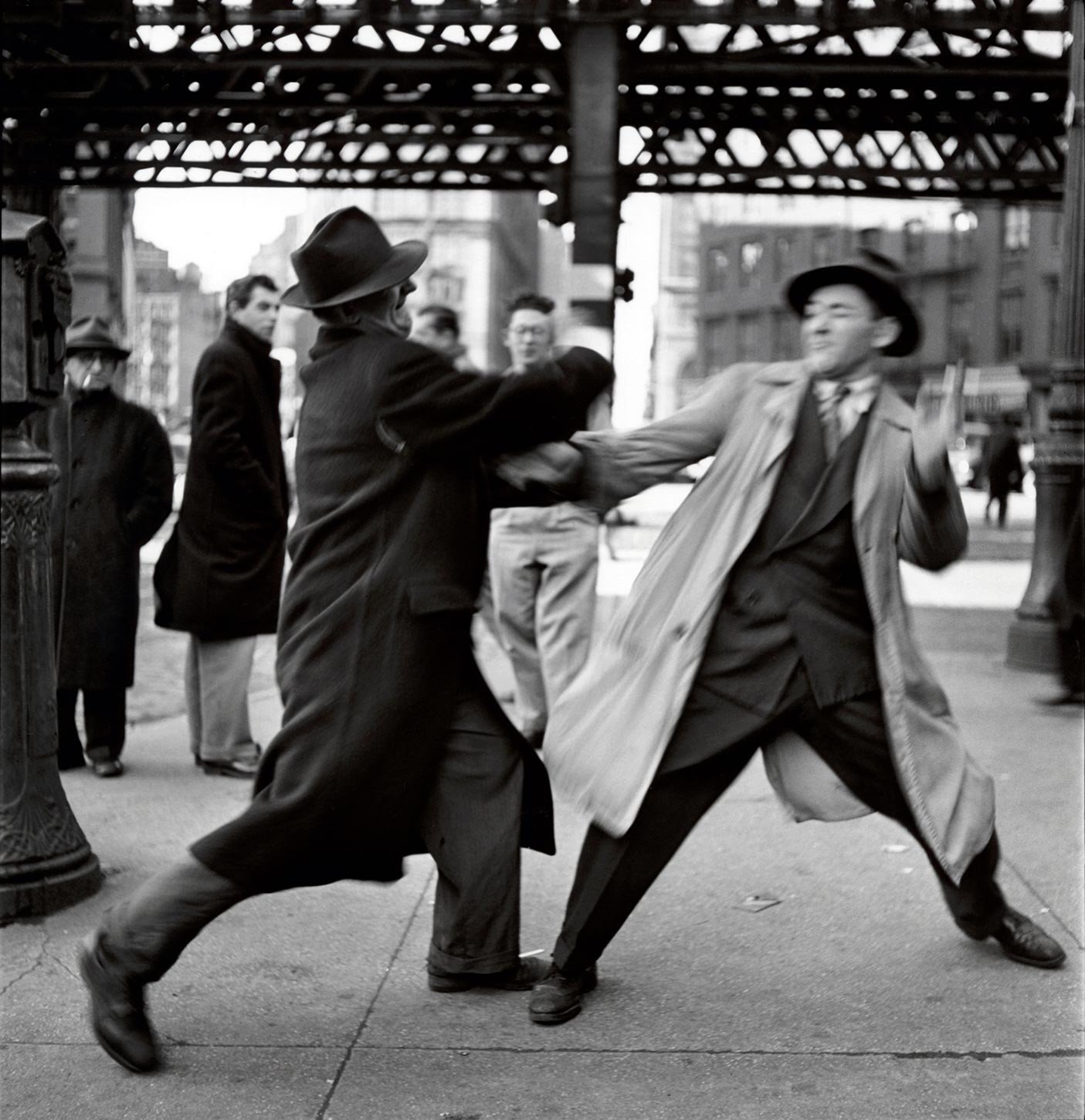

New York City, 1950. Photo by Elliott Erwitt. Buy it here.

Sir Ian McKellen delivers a stirring speech written by Shakespeare but never performed in his lifetime, as the play was banned by the Queen’s censor. Here, Sir Thomas More confronts a mob in London on May 1, 1517, as they riot and attack immigrants. (For more on the play and the historical background, look here.)

Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England;

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to the ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silenced by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions clothed;

What had you got? I’ll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quelled; and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an aged man,

For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

With self same hand, self reason, and self right,

Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes

Feed on one another.…

You’ll put down strangers,

Kill them, cut their throats, possess their houses,

And lead the majesty of law in lyam

To slip him like a hound. Alas, alas, say now the King,

As he is clement if th’offender mourn,

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you: whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbor? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, to Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers. Would you be pleas’d

To find a nation of such barbarous temper

That breaking out in hideous violence

Would not afford you an abode on earth.

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owned not nor made not you, nor that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But charter’d unto them? What would you think

To be thus used? This is the strangers’ case

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander (2012) is a devastating and important book. Alexander’s thesis will be difficult for well-intentioned people to accept: our 30-year “War on Drugs” and the resulting mass incarceration of African-American men is “a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow.”

Whether the drug war was purposely designed to immiserate African-Americans is not clear. Racist intent would be almost impossible to prove today; in our “color-blind” society, racists do not explicitly announce their motivations as they once did. I tend to be cynical about such things, but at this point the legislators’ intent hardly matters. Even if the mass incarceration of black men is an innocent, unintended consequence of the anti-drug crackdown, it is now an accomplished fact. It doesn’t matter how we got here; we are here now. The question is what to do about the problem. Acknowledging that the problem exists is a necessary first step.

I admit I was skeptical about Alexander’s conclusion. I still don’t buy all of it. But the statistics are overwhelming. I am a former prosecutor, I am not naive about the court system, but I was shocked by the numbers.

That the criminal justice system does not treat African-Americans equally is not news. It is the scale of the injustice that is so shocking, and the fact that the problem has gotten so much worse so recently. Go back, read those numbers again.

We like to think that history equals progress — that over time, things get better. In many ways, of course, they do. But progress is never guaranteed and never uniform. The New Jim Crow is a sobering reminder of that, particularly at a moment in our politics when wisdom and compassion seem to be in short supply.

The [Efficient Plots Hypothesis], as I imagine it, says that the ideal reader can’t know if the mood of a book is about to get sunnier or darker at any given point in the plot. This … [is] because the purpose of a narrative is to engross the reader. Engrossment proceeds through uncertainty. If you knew what was about to happen, you’d skim ahead or stop reading.

That is: at any moment in a story, the emotional trajectory is a random walk for the reader because anything else would be boring. And stories aren’t boring.

This could be tested empirically by asking readers if a book will get more positive or more negative over the next five pages, and by how much. In a pure EPH world, they’ll only be right about half the time.

…

If the EPH holds, then, it doesn’t suggest that fiction is truly arbitrary; rather, that it’s an elaborately constructed game between reader and writer, socially conditioned and in no way permanent. It would suggest that there are enough fundamental plots that at any point in a book you are unsure what plot you are in; and that plots tend to wear themselves out over time.

Read about it here.

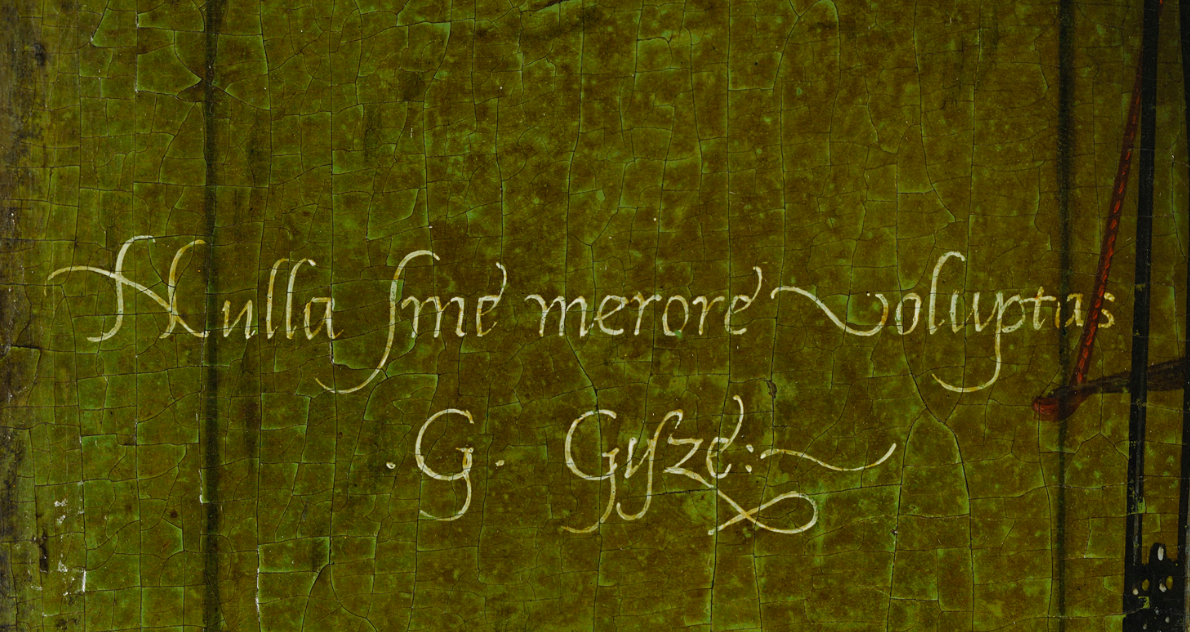

“Nulla sine merore voluptas” — no joy without sorrow. Detail from “The Merchant Georg Gisze” by Holbein (1532).