This photo, by Frans Lanting for National Geographic, has not been Photoshopped or retouched in any way. It shows a place called Dead Vlei in Namibia in the early light of dawn. Details about the making of the photo are here. (Via PDN.)

Art

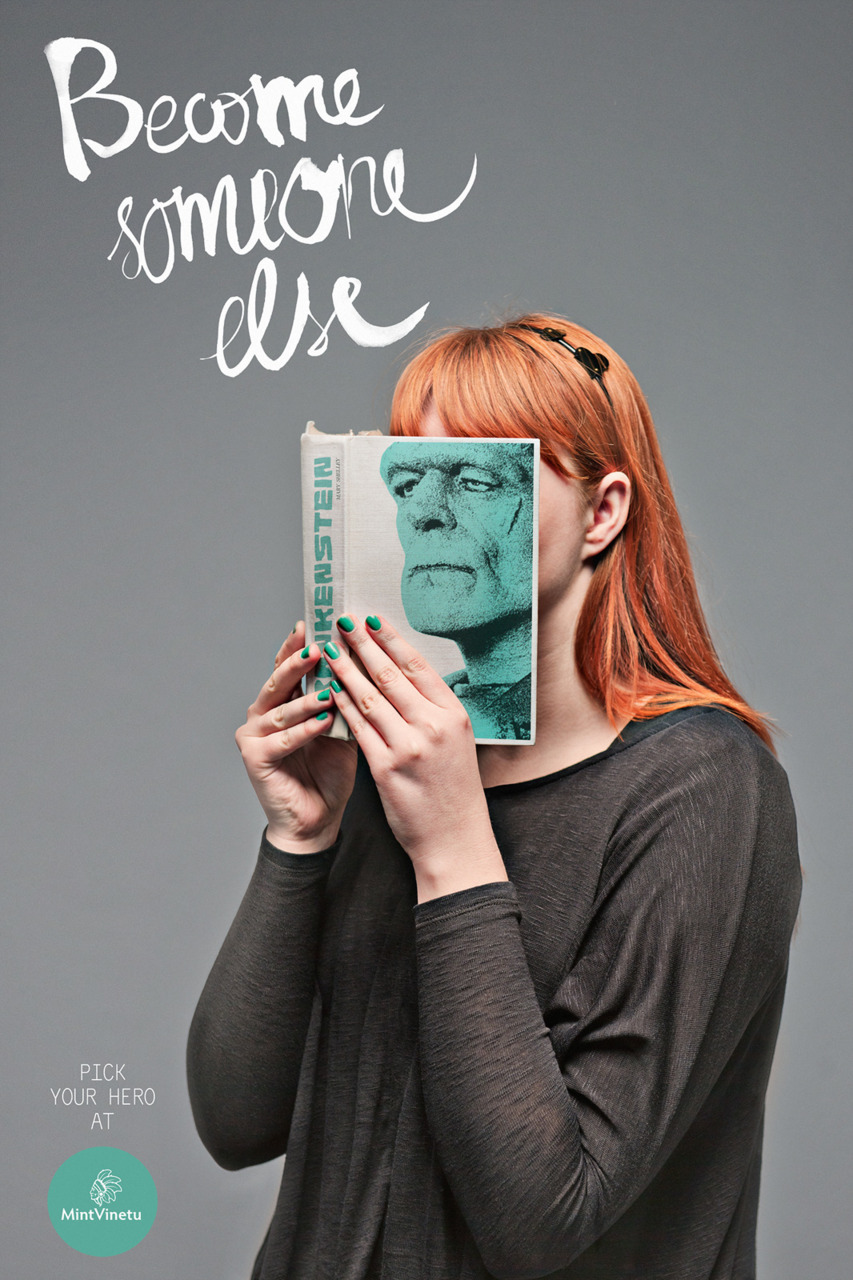

You are what you read

Wonderful ad for a bookstore in Lithuania called Mint Vinetu. (Via Quipsologies.)

Robert Longo: Shark

Robert Longo

Untitled (Shark 4)

2008

Charcoal on mounted paper

88 x 70 inches/223.5 x 177.8 cm

Why are we attracted to crime stories?

Why do ordinary readers happily devour crime novels, the sort of stories I write, about violence — murder above all — and every conceivable sort of treachery? Why do housewives and business travelers and grandmothers — people who would not themselves steal a stick of gum — feel drawn to crime stories, fascinated by them?

John le Carré seems to have puzzled over the appeal of spy novels in a similar way. The other day I ran across this quote:

Most of us live in a condition of secrecy: secret desires, secret appetites, secret hatreds, and relationship with the institutions which is extremely intense and uncomfortable. These are, to me, a part of the ordinary human condition. So I don’t think I’m writing about abnormal things.… Artists, in my experience, have very little center. They fake. They are not the real thing. They are spies. I am no exception.

I think le Carré gets that exactly right. We are all spies. We all fake, one way or another, at times. Spies perfectly embody this aspect of human nature.

Are we all criminals, too? Is that why we rush to buy books by Lee Child or Richard Price or Michael Connelly? Is that why the news media cover crime stories with such obvious relish?

Maybe. When asked to explain the attraction of crime stories, I have always fallen back on the phrase “bad men do what good men dream,” which was coined by the psychologist Robert I. Simon (it is the title of Simon’s book). Simon writes,

The basic difference between what are socially considered to be bad and good people is not one of kind, but one of degree, and of the ability of the bad to translate dark impulses into dark actions. Bad men such as serial sexual killers have intense, compulsive, sadistic fantasies that few good men have, but we all have some measure of that hostility, aggression, and sadism. Anyone can become violent, even murderous, under certain circumstances. Our brains are wired for aggression, and can short-circuit into violence.

It is a powerful, frightening idea. But even if it is true — even if we are all criminals with secret dark instincts, however faintly we feel them, however well we master them — it still does not explain the precise nature of our attraction to crime stories. When we read crime novels, are we indulging this secret urge to violence, acting out fantasies? Are we good men (people) dreaming of doing bad things? Our favorite criminals — Hannibal Lecter, Michael Corleone — do have an undeniable glamor.

On the other hand, maybe we read crime stories to relieve the anxiety that we will become victims. Maybe the pleasure is in the experience of control over these demons. Most crime stories end with the villain’s defeat, after all. Justice tends to triumph in fiction more often than it does in real life. Surely that is no accident.

Or perhaps we enjoy crime stories for the same reason we go to horror movies and roller coasters: to feel the thrill of fear. To get the adrenaline rush of a dangerous situation without the risk of actual danger.

I suspect that the precise nature of our attraction to crime stories is murkier than le Carré’s theory about spy novels. We may indeed all be spies, but we are not all criminals — not just criminals, anyway. We are good and bad, cops and robbers, heroes and villains, at different times. As a crime novelist, that strikes me as good news. Novels thrive in the murk of human emotions.

Inactivity

“Inactivity” by Bryan Christie Design.

Rilke: “The Man Watching”

I can tell by the way the trees beat, after

The storm, the shifter of shapes, drives on

What we choose to fight is so tiny!

When we win it’s with small things,

Whoever was beaten by this Angel

— Rainer Maria Rilke. Translation by Robert Bly.

This is how writers grow, too: by being defeated, decisively, by constantly greater challenges.

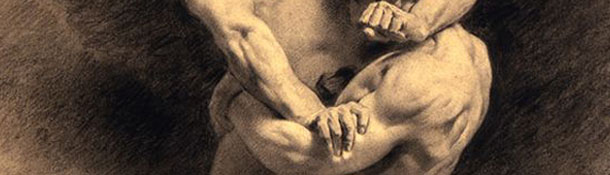

Image: detail from Léon Bonnat, “Jacob Wrestling the Angel,” 1876. Pencil and black chalk on paper. 20¾ x 14½ in. (via)