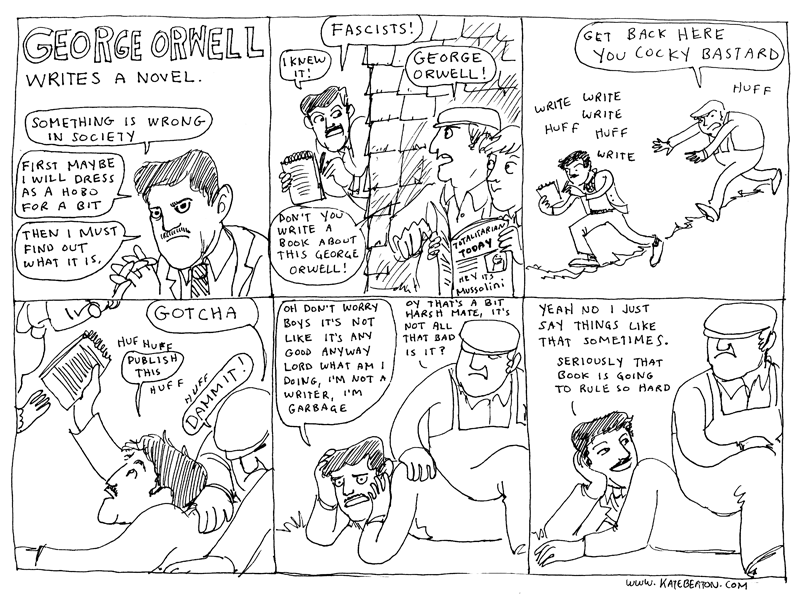

Via. (Click image to view full size.)

Official website of the author

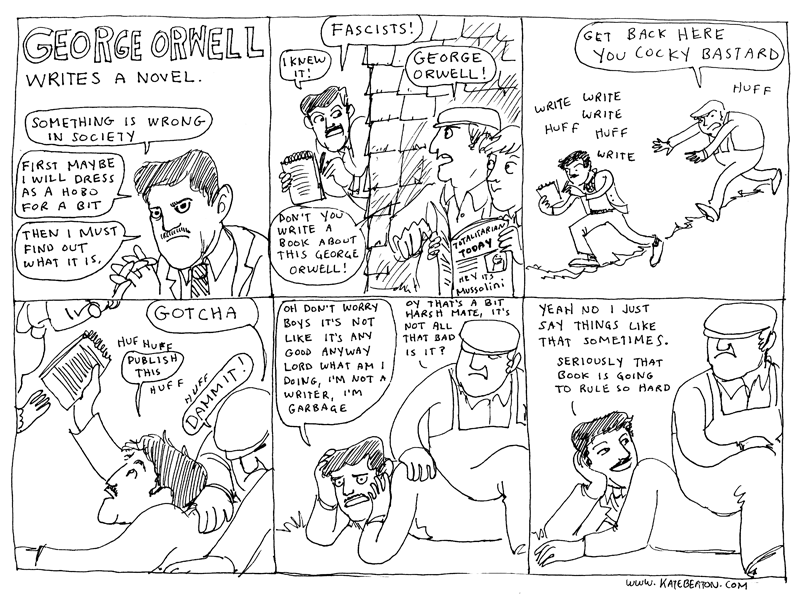

Via. (Click image to view full size.)

So what are books good for? My best answer is that books produce knowledge by encasing it. Books take ideas and set them down, transforming them through the limitations of space into thinking usable by others.… [T]he two cultures of the contemporary world are the culture of data and the culture of narrative. Narrative is rarely collective. It isn’t infinitely expandable. Narrative has a shape and a temporality, and it ends, just as our lives do. Books tell stories. Scholarly books tell scholarly stories.

— William Germano

Read the whole essay here. I’m not sure there’s really anything new in it, but it is an interesting consideration of what the word “book” means in the digital era and a good case for the continuing relevance of the codex — you know, the kind of book made out of paper, ink and glue. (via ALD)

“A novel can educate to some extent, but first a novel has to entertain. That’s the contract with the reader: you give me ten hours and I’ll give you a reason to turn every page. I have a commitment to accessibility. I believe in plot. I want an English professor to understand the symbolism while at the same time I want the people I grew up with — who may not often read anything but the Sears catalog — to read my books.”

Sometimes in reading at random, weird patterns emerge. The last couple of days I ran across these two quotes, both trashing sacred-cow novelists. In the first, from The Paris Review in 1963, Katherine Anne Porter explains why she detests F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Not only didn’t I like [Fitzgerald’s] writing, but I didn’t like the people he wrote about. I thought they weren’t worth thinking about, and I still think so. It seems to me that your human beings have to have some kind of meaning. I just can’t be interested in those perfectly stupid meaningless lives.

The next is from B.R. Myers’ acid review of Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Freedom, in The Atlantic:

One opens a new novel and is promptly introduced to some dull minor characters. Tiring of them, one skims ahead to meet the leads, only to realize: those minor characters are the leads. A common experience for even the occasional reader of contemporary fiction, it never fails to make the heart sink. The problem is not only one of craft or execution. Characters are now conceived as if the whole point of literature were to create plausible likenesses of the folks next door. They have their little worries, but so what? Do writers really believe that every unhappy family is special? … Granted, nonentities are people too, and a good storyteller can interest us in just about anybody, as Madame Bovary demonstrates. But … whatever is wrong with these people [i.e. the characters in Freedom] does not matter.

I won’t get into the mean-spiritedness of these reviews, except to say that they capture why I could never be a book critic. (I do post book reviews on this blog, but never negative ones. If I can’t recommend a book, I simply don’t mention it.) And I’m not especially interested in the merits of these opinions, either, though Porter’s dismissal of Fitzgerald seems asinine to me. (I haven’t read Freedom.)

But they do raise an interesting question: what makes an insipid character worth writing and reading about? Obviously it is not as simple as “dull characters, dull book,” as Myers’ example of Madame Bovary makes clear. (My choice would have been Mrs. Dalloway). Is it only the skill of the novelist that grants significance to minor lives? Or do the shallow protagonists of successful books share common characteristics — are they shallow in some distinctive, dramatically advantageous way? If it had been Flaubert rather than Franzen writing about ordinary folks in Minnesota, would it have made a difference to readers like B.R. Myers, who evidently feels the whole project was doomed from the start merely by Franzen’s choice of subject?

The problem [Pauline] Kael undertook to address when she began writing for The New Yorker was the problem of making popular entertainment respectable to people whose education told them that popular entertainment is not art. This is usually thought of as the high-low problem — the problem that arises when a critic equipped with a highbrow technique bends his or her attention to an object that is too low, when the professor writes about Superman comics. In fact, this rarely is a problem: if anything profits from (say) a semiotic analysis, it’s the comics. The professor may go on to compare Superman comics favorably with Homer, but that is simply a failure of judgment. It has nothing to do with the difference in brows. You can make a fool of yourself over anything.

The real high-low problem doesn’t arise when the object is too low. It arises when the object isn’t low enough. Meet the Beatles doesn’t pose a high-low problem; Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band does. Tom Clancy and Wheel of Fortune don’t; John le Carré and Masterpiece Theater do. A product like Sgt. Pepper isn’t low enough to be discussed as a mere cultural artifact; but it’s not high enough to be discussed as though it were Four Quartets, either. It’s exactly what it pretends to be: it’s entertainment, but for educated people. And this is what makes it so hard for educated people to talk about without sounding pretentious — as though they had to justify their pleasure by some gesture toward the ‘deeper’ significance of the product.

— Louis Menand, “Finding It at the Movies,” New York Review of Books, 3/23/95

People without hope not only don’t write novels, but what is more to the point, they don’t read them. They don’t take long looks at anything, because they lack the courage. The way to despair is to refuse to have any kind of experience, and the novel, of course, is a way to have experience.

Flannery O’Connor (via)

If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.

Haruki Murakami, Norwegian Wood

Media evolution, of course, does claim casualties. But most often, these are means of distribution or storage, especially physical ones that can be transformed into digital bits. Photographic film is supplanted, but people take more pictures than ever. CD’s no longer dominate, as music is more and more distributed online. “Books, magazines and newspapers are next,” predicts Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the M.I.T. Media Lab. “Text is not going away, nor is reading. Paper is going away.”

— New York Times, 8.22.10