“The art lies in concealing the art.”

Horace

Official website of the author

“The art lies in concealing the art.”

Horace

We tend to think of procrastination as a personal failing, even a moral flaw, a sin. For novelists in particular, marooned at our lonely desks and in our heads, facing enormous tasks and distant deadlines, procrastination is a besetting danger. The web makes the problem infinitely worse, with its little cruelty of turning the writer’s workspace, his computer screen, into an endless cabinet of wonders. Distraction is always just two clicks away.

There is now a small industry churning out advice on how to stay productive in the age of distraction, but it all boils down to this: put away your toys and get to work. In his wonderful The War of Art, Steven Pressfield advises, “Be a pro.” And that, honestly, is the bottom line. Just do it.

Personally, I try to live by that advice. By nature I am lazy and undisciplined, a lifelong procrastinator, so I rely on a set of formal strategies to stay focused. I work in a barren office, on an ancient ThinkPad T23 laptop that has no internet capability. I cripple my smart phone using various apps. (I fiddle constantly with how best to disable my phone during work hours, which, yes, I know.) When all else fails, I leave the damn phone at home.

Fellow weak-willed writers, I can’t say this strongly enough: do not burn energy resisting the temptation of the web. Just turn it off completely. Unplug. Research has shown that people who exhibit strong willpower are not better at resisting temptation; they simply do not expose themselves to temptation. They do not bravely refuse to eat the ice cream in the freezer; they never go down the frozen-food aisle in the supermarket in the first place.

Once I have unplugged from the web, I focus on starting. Not writing a whole novel or even a single scene, not writing for a certain period of time or hitting some daily word-quota. Just starting. As a writer, that is the most essential and difficult thing you will do: start. You must learn to start and start and start. Every morning, despite the awesome scale of the task, despite your own mounting anxiety, you must start. You will fail, of course. All writers fail. Most writers fail most of the time. Doesn’t matter. Get up, dust yourself off, and start again. If you start enough, in some small percentage of those attempts, you will achieve the blessed, transporting, trance-like state of flow that every writer treasures, and the residue of that deeply-focused work will be words on the page.

So that is my anti-procrastination strategy. In two words: unplug and start. I do not claim there is any special wisdom there, nor do these strategies work infallibly for me. I fail all the time, and I scourge myself for it. Probably you do, too. if you are a writer. It seems to be a universal feeling in this job. But failure is part of writing. Tomorrow you will try again. What choice is there? As Beckett said, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

With all that said, I would like to suggest that some procrastination is actually good. Yes, good. Sometimes a writer resists writing not because he is lazy or careless, but because the passage just isn’t ready to be written. Hemingway famously said, “The most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in, shockproof, shit detector.” Sometimes the way your shit detector goes off is by refusing to allow you to write shit in the first place.

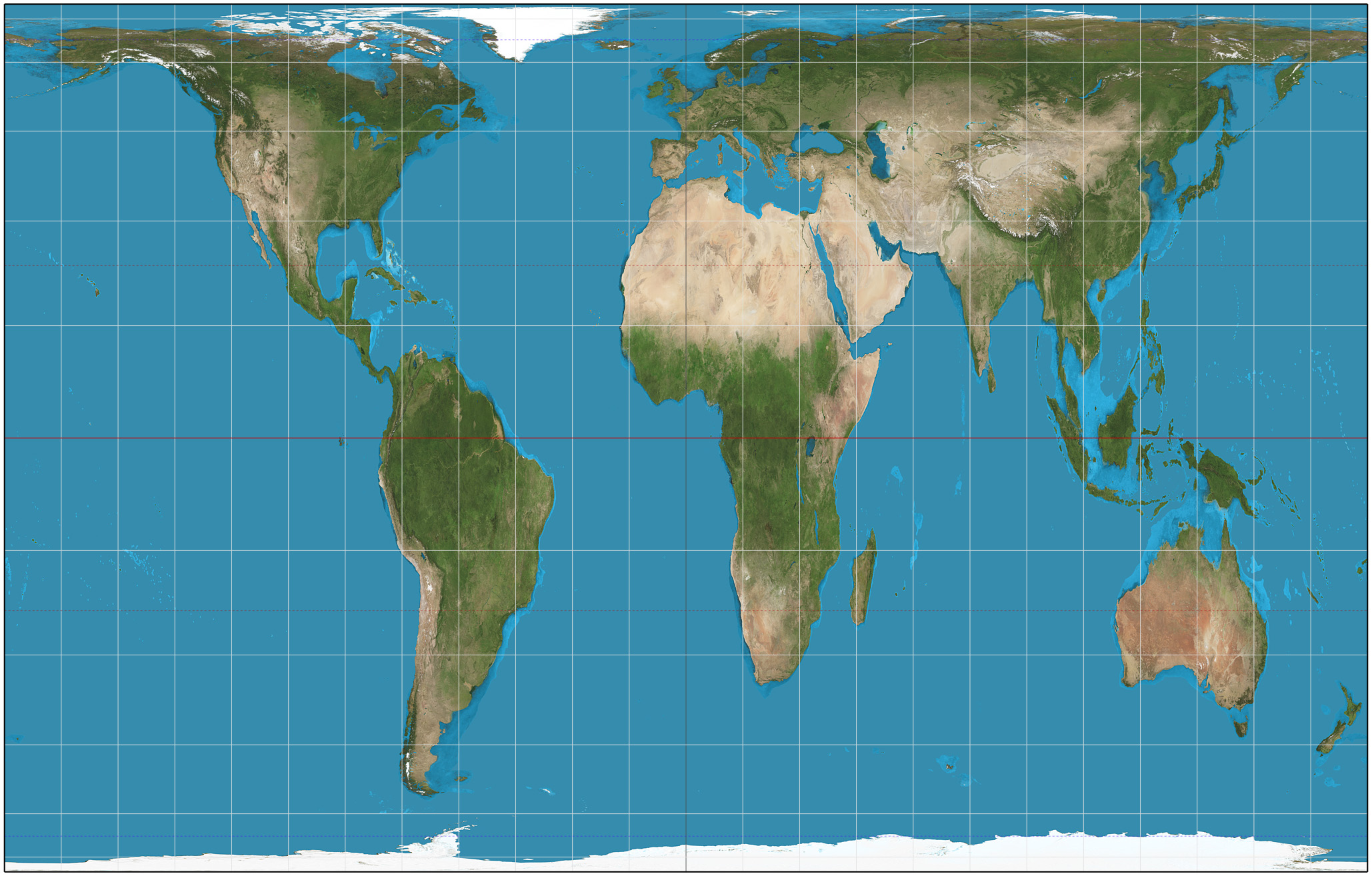

The Gall-Peters projection map, showing the true relative size of the continents without the distortion of the traditional Mercator projection. (As usual, “The West Wing” got there first.)

When we encounter a natural style, Pascal says, we are surprised and delighted, because we expected to find an author and instead found a man.

A 1960 interview with Orson Welles about “Citizen Kane.”

Q: What I’d like to know is where did you get the confidence from to make the film with such —

A: Ignorance. Ignorance. Sheer ignorance. You know, there’s no confidence to equal it. It’s only when you know something about a profession, I think, that you’re timid, or careful or —

Q: How does this ignorance show itself?

A: I thought you could do anything with a camera that the eye could do or the imagination could do. And if you come up from the bottom in the film business, you’re taught all the things that the cameraman doesn’t want to attempt for fear he will be criticized for having failed. And in this case I had a cameraman who didn’t care if he was criticized if he failed, and I didn’t know that there were things you couldn’t do, so anything I could think up in my dreams, I attempted to photograph.

Q: You got away with enormous technical advances, didn’t you?

A: Simply by not knowing that they were impossible. Or theoretically impossible. And of course, again, I had a great advantage, not only in the real genius of my cameraman, but in the fact that he, like all great men, I think, who are masters of a craft, told me right at the outset that there was nothing about camerawork that I couldn’t learn in half a day, that any intelligent person couldn’t learn in half a day. And he was right.

Q: It’s true of an awful lot of things, isn’t it?

A: Of all things.

Looking up Boylston Street from the corner of Berkeley in the 19th century. At right is the New England Museum of Natural History, a predecessor of the Boston Museum of Science. (The building is now occupied by Restoration Hardware — sigh.) To its left is the Boston Institute of Technology, now MIT. The tower at the far left is Old South Church in Copley Square. (via) I work nearby and pass this spot every day.