I’m pretty obsessive once I get going. I tend to throw everything at it, and I’m generally rather happy if I’m making progress of 450 to 500 words a day. I work from 9:30 in the morning. If things are going, I see no reason to stop, because I know there’s a point I’ll get to, a moment of hesitation, and a day or a week will pass before I see the way through.

Sometimes, I work late at night, sometimes into the early hours if things are going along. I spend a lot of time at the beginning of a day looking over things from the day before. I was a very early adopter of word processing back in the early ’80s. Being able to constantly correct is good for writers.

I think you do need to come away, somewhere along the line, and let it sit, so you can come back with a completely fresh eye and almost regard it as the work of a stranger.

Blog

On Voluptas

“Nulla sine merore voluptas” — no joy without sorrow. Detail from “The Merchant Georg Gisze” by Holbein (1532).

Auden: “a genuine writer forgets”

Just as a good man forgets his deed the moment he has done it, a genuine writer forgets a work as soon as he has completed it and starts to think about the next one; if he thinks about his past work at all, he is more likely to remember its faults than its virtues. Fame often makes a writer vain, but seldom makes him proud.

How Styron wrote

The previous summer, Styron had begun [The Confessions of Nat Turner]. He nudged a No. 2 pencil across sheets of yellow legal paper, each sentence polished before he moved on to the next. The most methodical of novelists, he demanded utter silence, even with small children in the house. He had a stone wall built in front to try to muffle the noise of passing vehicles, according to his daughter Alexandra in her 2011 memoir, Reading My Father. His pattern was all but inviolate. Up at noon, leisurely lunch or brunch with Rose. Push away from the table at two o’clock for a long walk with his dogs, while he organized his thoughts for the afternoon siege. Then, into the barn until he emerged at 7:30 with “my painful 600 words,” which he refined some more over a drink at the bar and then gave to Rose for typing, about two and a half pages in all. Once he was done he tinkered very little. “This guy does not revise heavily and start all over again,” says his longtime editor, Robert Loomis, aged 89. “Bill’s first draft was essentially his final draft.”

Sam Tanenhaus, “The Literary Battle for Nat Turner’s Legacy” (great read)

“My painful 600 words.” I know the feeling. It took William Styron four and a half years to complete The Confessions of Nat Turner.

“The Year of Lear”

Shakespeare became a god long ago. He exists outside history, eternal, unconfined by any particular historical moment. He is literally timeless. In The Year of Lear, James Shapiro swats away all the writer-god stuff and plunks us down with Shakespeare in grubby, plague-ravaged, terrorized London in 1606. It is probably as close as we can come to glimpsing the man himself; too little is known about Shakespeare’s life to reconstruct a proper biography. And for a writer like me, it is stirring to see Shakespeare grapple in his plays with the obsessions and anxieties of Jacobean England — fear of a bloody succession battle, the hunt for Catholic recusants, the Gunpowder Plot (the 9/11 of its day), witchcraft, demonic possession, on and on. Just a working writer at his desk, in a dirty, day-old shirt, his thoughts tossed around like all of us. It’s a great read.

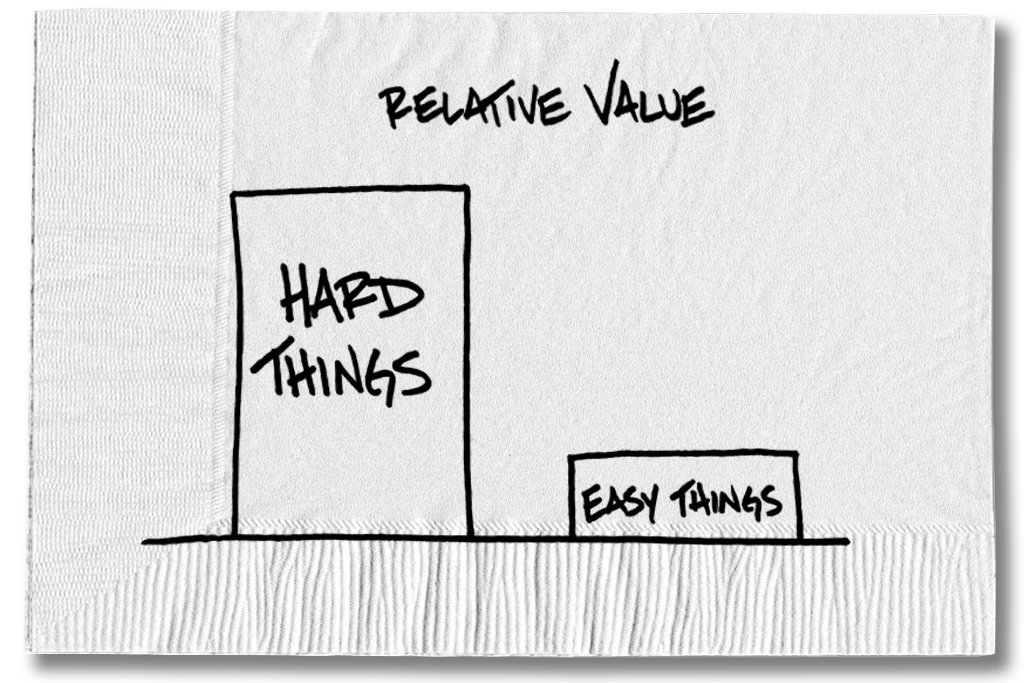

If it’s hard, why do it?

This graphic, from a story in the Times the other day, pretty well captures the appeal of novel-writing for me. You do it precisely because it’s difficult.

Writing as meditation

I see writing as a form of meditation, where I can let everything else fall away for a few moments and just stay with this one activity. It means I need to get my mind into the writing space, notice when the urge to go to distraction comes up, and not just automatically follow the urge. I can look within myself and let feelings flow out through the written word, or see the truths within me and try to channel those onto the page.

Leo Babauta, “Training To Be a Good Writer“

Quote of the day

I’m most in awe of novelists, who move sets, lights, scenery, and act out all the parts in your mind for you. My kind of writing requires collaboration with others to truly ignite. But I think of Dickens, or Cervantes, or Márquez, or Morrison, and I can describe to you the worlds they paint and inhabit. To engender empathy and create a world using only words is the closest thing we have to magic.