My lifetime ambition has been to unite the utmost seriousness of question with the utmost lightness of form.

Milan Kundera (via theparisreview)

Official website of the author

My lifetime ambition has been to unite the utmost seriousness of question with the utmost lightness of form.

Milan Kundera (via theparisreview)

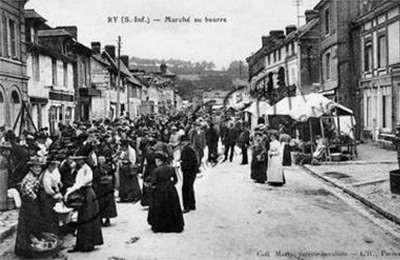

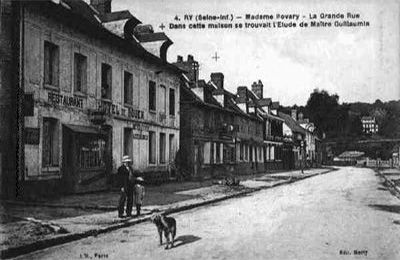

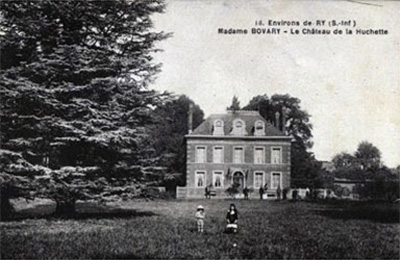

Lydia Davis’s new translation of Madame Bovary is terrific. With my klutzy high-school French, I am not qualified to judge the accuracy of the translation (Julian Barnes does that here). All I can say is I enjoyed the book on this rereading much more than I have in the past, when reading it felt like swimming upstream. It may be that I was simply too young for the book on my first, joyless read. This time I loved it.

Davis’s version of the novel feels quite contemporary in style. Of course, part of the credit for that goes to Davis, herself a graceful fiction writer. But the larger point is that, in September 1851 when he sat down to begin writing Madame Bovary, in his second-floor study using a quill pen, Flaubert envisioned something radically new — what we recognize now as the modern realist novel. Like the old joke about the fish who cannot see the water all around him (“What water?”), it is hard for contemporary readers to see what Flaubert is doing in Madame Bovary that is so innovative. As Davis explains in her foreword to the new translation, the novel “is now viewed as the first masterpiece of realist fiction. Yet its radical nature is paradoxically difficult for us to see; its approach is familiar to us for the very reason that Madame Bovary permanently changed the way novels were written thereafter.” Realism — the mimetic, naturalistic depiction of human experience — is the water that all of us, writers and readers, now swim in.

It is too much to say that Flaubert invented realism with Madame Bovary, but he has a pretty good claim as the author who envisioned it most clearly and actually captured it. His intent in writing Bovary, in the words of biographer Frederick Brown, was to “[make] the world materially present through language — [to abolish] the space between words and what they represent.” He wanted to capture life as it is actually experienced, without commentary or embellishment. “No lyricism, no reflections,” Flaubert declared in a letter, “the personality of the author absent.”

[Read more…] about “Madame Bovary” translated by Lydia Davis

Commonwealth Avenue, Back Bay, Boston, ca. 1904. (via)

Army-Navy game, Polo Grounds, New York, 1916. (via)

“Write about the thing that frightens you most.”

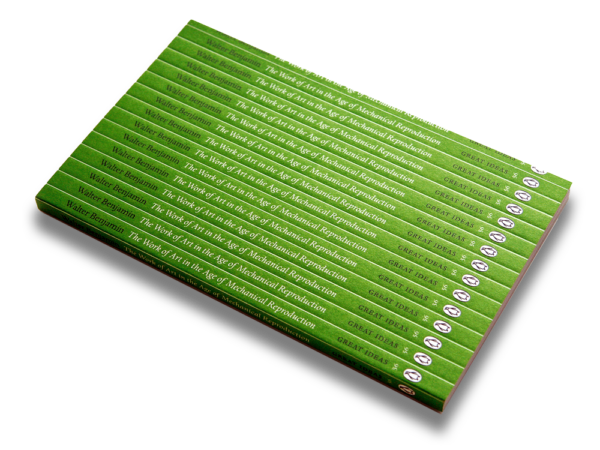

Brilliant cover art for Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Designed by David Pearson for Penguin’s Great Ideas series, vol. 3 (2008). (Via Flickr.) Perfect.

New York City. October 19, 1960. (via)