Robert Longo

Untitled (Shark 4)

2008

Charcoal on mounted paper

88 x 70 inches/223.5 x 177.8 cm

Blog

Golden Gate Bridge under construction

Robert Campbell on Boston’s Human Scale

Boston’s Old State House … was a perfectly normal-sized building when it was erected, in 1713. But today, surrounded by skyscrapers, it is completely transformed. It possesses a new charm, a charm its architect could never have envisioned: the charm of a tiny jewel or an exquisite ivory carving. Or a child. Among the tall, blank, dark buildings that surround it, the Old State House, with its slightly loony ornaments — a lion and a unicorn — resembles a child in Halloween costume being escorted around the neighborhood by the FBI.

What is true of the Old State House as a building is equally true of Boston as a city. Once Boston, too, was a city of average scale. That’s not the case anymore, not when you compare Boston with the typical American megalopolis, with its vast, bleak stretches of freeway and strip malls. By contrast, we’ve become Tiny Town.

Quite literally so. Boston comprises just 46 square miles of total area. Phoenix is 324, Los Angeles, 465, Honolulu, 596. The new Denver airport is bigger than all of Boston. You could put Louisburg Square in the center strip of many American downtown arteries and forget where you’d left it; it would resemble a minor traffic island. Or take our so-called skyscrapers. No fewer than 12 other US cities boast towers higher than the Hancock, our tallest. Chicago and New York between them have 22. There are several reasons why our buildings are smaller, the most important of which is that most of Boston’s subsoil is muck, not bedrock like Manhattan’s. By the time technology had solved the foundation problem, Bostonians were used to their smaller scale.…

[O]ur perception of scale has a lot to do with our life cycle as human beings. We were all small once, and we all got bigger. In that sense, we are all Alice in Wonderland: In our imaginations and our dreams, we’re always growing and shrinking. When we were little, a table was huge; we couldn’t see over the top of it. The memory of being so overwhelmed is one reason we enjoy miniatures, like doll houses and architectural models.… Why else do we flock to the famous “Main Streets” at Disneyland and Walt Disney World? All the buildings along these streets are built at three-quarters the size they would be in real life. The Disney people always get us right: In a world grown too big, we gravitate to a street that is just a little bit too small. It makes us feel more important, and it makes the world feel more manageable.

…When the “wrong” size is too big, it may command awe. When it is too small, it will often inspire love.

Boston, more than any other major American city, is a place that is filled with opportunities for that kind of affection.

Robert Campbell, “Small Wonders”

Why are we attracted to crime stories?

Why do ordinary readers happily devour crime novels, the sort of stories I write, about violence — murder above all — and every conceivable sort of treachery? Why do housewives and business travelers and grandmothers — people who would not themselves steal a stick of gum — feel drawn to crime stories, fascinated by them?

John le Carré seems to have puzzled over the appeal of spy novels in a similar way. The other day I ran across this quote:

Most of us live in a condition of secrecy: secret desires, secret appetites, secret hatreds, and relationship with the institutions which is extremely intense and uncomfortable. These are, to me, a part of the ordinary human condition. So I don’t think I’m writing about abnormal things.… Artists, in my experience, have very little center. They fake. They are not the real thing. They are spies. I am no exception.

I think le Carré gets that exactly right. We are all spies. We all fake, one way or another, at times. Spies perfectly embody this aspect of human nature.

Are we all criminals, too? Is that why we rush to buy books by Lee Child or Richard Price or Michael Connelly? Is that why the news media cover crime stories with such obvious relish?

Maybe. When asked to explain the attraction of crime stories, I have always fallen back on the phrase “bad men do what good men dream,” which was coined by the psychologist Robert I. Simon (it is the title of Simon’s book). Simon writes,

The basic difference between what are socially considered to be bad and good people is not one of kind, but one of degree, and of the ability of the bad to translate dark impulses into dark actions. Bad men such as serial sexual killers have intense, compulsive, sadistic fantasies that few good men have, but we all have some measure of that hostility, aggression, and sadism. Anyone can become violent, even murderous, under certain circumstances. Our brains are wired for aggression, and can short-circuit into violence.

It is a powerful, frightening idea. But even if it is true — even if we are all criminals with secret dark instincts, however faintly we feel them, however well we master them — it still does not explain the precise nature of our attraction to crime stories. When we read crime novels, are we indulging this secret urge to violence, acting out fantasies? Are we good men (people) dreaming of doing bad things? Our favorite criminals — Hannibal Lecter, Michael Corleone — do have an undeniable glamor.

On the other hand, maybe we read crime stories to relieve the anxiety that we will become victims. Maybe the pleasure is in the experience of control over these demons. Most crime stories end with the villain’s defeat, after all. Justice tends to triumph in fiction more often than it does in real life. Surely that is no accident.

Or perhaps we enjoy crime stories for the same reason we go to horror movies and roller coasters: to feel the thrill of fear. To get the adrenaline rush of a dangerous situation without the risk of actual danger.

I suspect that the precise nature of our attraction to crime stories is murkier than le Carré’s theory about spy novels. We may indeed all be spies, but we are not all criminals — not just criminals, anyway. We are good and bad, cops and robbers, heroes and villains, at different times. As a crime novelist, that strikes me as good news. Novels thrive in the murk of human emotions.

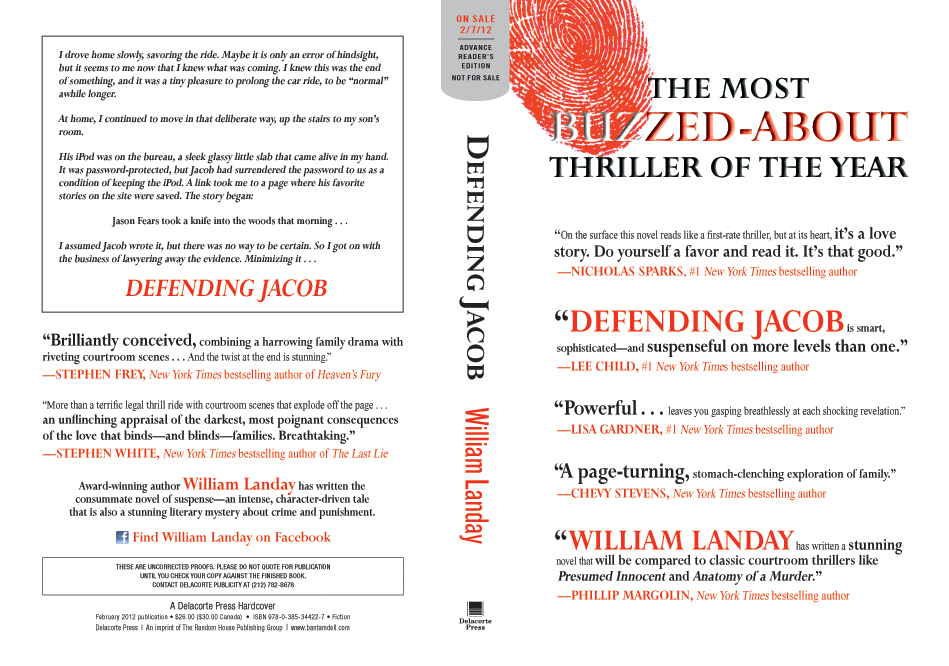

Pre-first edition

A sneak peek at the cover for an advance promo copy — an ARE, or advance review edition, in Random House parlance — of my new novel. This is how buzz is built (we hope).

Inactivity

“Inactivity” by Bryan Christie Design.

Orhan Pamuk: “A writer is…”

A writer is someone who spends years patiently trying to discover the second being inside him and the world that makes him who he is. When I speak of writing, what comes first to my mind is not a novel, a poem, or literary tradition; it is a person who shuts himself up in a room, sits down at a table, and alone, turns inward. Amid its shadows, he builds a new world with words. This man — or this woman — may use a typewriter, profit from the ease of a computer, or write with a pen on paper, as I have done for thirty years. As he writes, he can drink tea or coffee, or smoke cigarettes. From time to time he may rise from his table to look out through the window at the children playing in the street, and, if he is lucky, at trees and a view, or he can gaze out at a black wall. He can write poems, plays, or novels, as I do. All these differences come after the crucial task of sitting down at the table and patiently turning inwards. To write is to turn this inward gaze into words, to study the world into which that person passes when he retires into himself, and to do so with patience, obstinacy, and joy.

— Orhan Pamuk, from his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature, December 2006 (via)

The Ignorance of Voters

The human mind is simply terrible at politics. Although we think we make political decisions based upon the facts, the reality is much more sordid. We are affiliation machines, editing the world to confirm our partisan ideologies.