“It’s difficult to accept what your psyche or history dooms you to write, what Faulkner would call your postage stamp of reality. Young writers often mistakenly choose a certain vein or style based on who they want to be, unconsciously trying to blot out who they actually are.”

Blog

Stranded

Last Wednesday evening in New York, Defending Jacob won the Strand Magazine Critics Award for best novel (details here). Here I am at the award ceremony with fellow honorees Matthew Quirk, who won the Best Debut Novel award for The 500, and Faye Kellerman, who won a lifetime achievement award. A nice night. Many thanks to the Strand. (Photo by yet another best-selling author, Alan Jacobson.)

Library Way

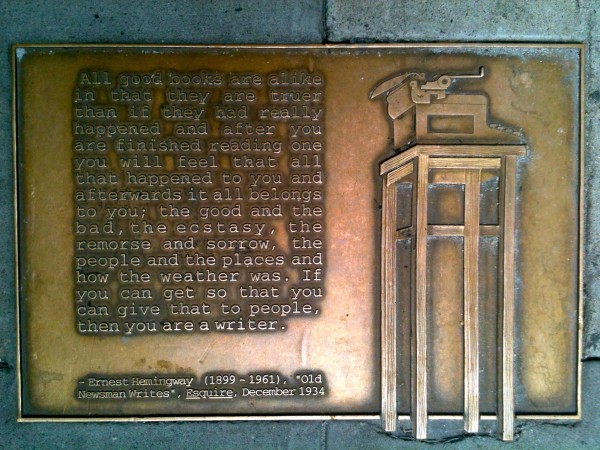

This is from a series of lovely plaques set into the sidewalk pavement on 41st Street leading up to the New York Public Library. Each includes a brief quote, some inspirational, some about books and reading. It took me twenty minutes to go two blocks. I love, also, that this plaque includes Hemingway’s standing desk (though it is rendered with an Escher-esque perspective error on the right rear leg, which is shown in front of the side brace rather than behind it). The plaque reads:

All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it all belongs to you; the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was. If you can get so that you can give that to people, then you are a writer.

— Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), “Old Newsman Writes,” Esquire, December 1934

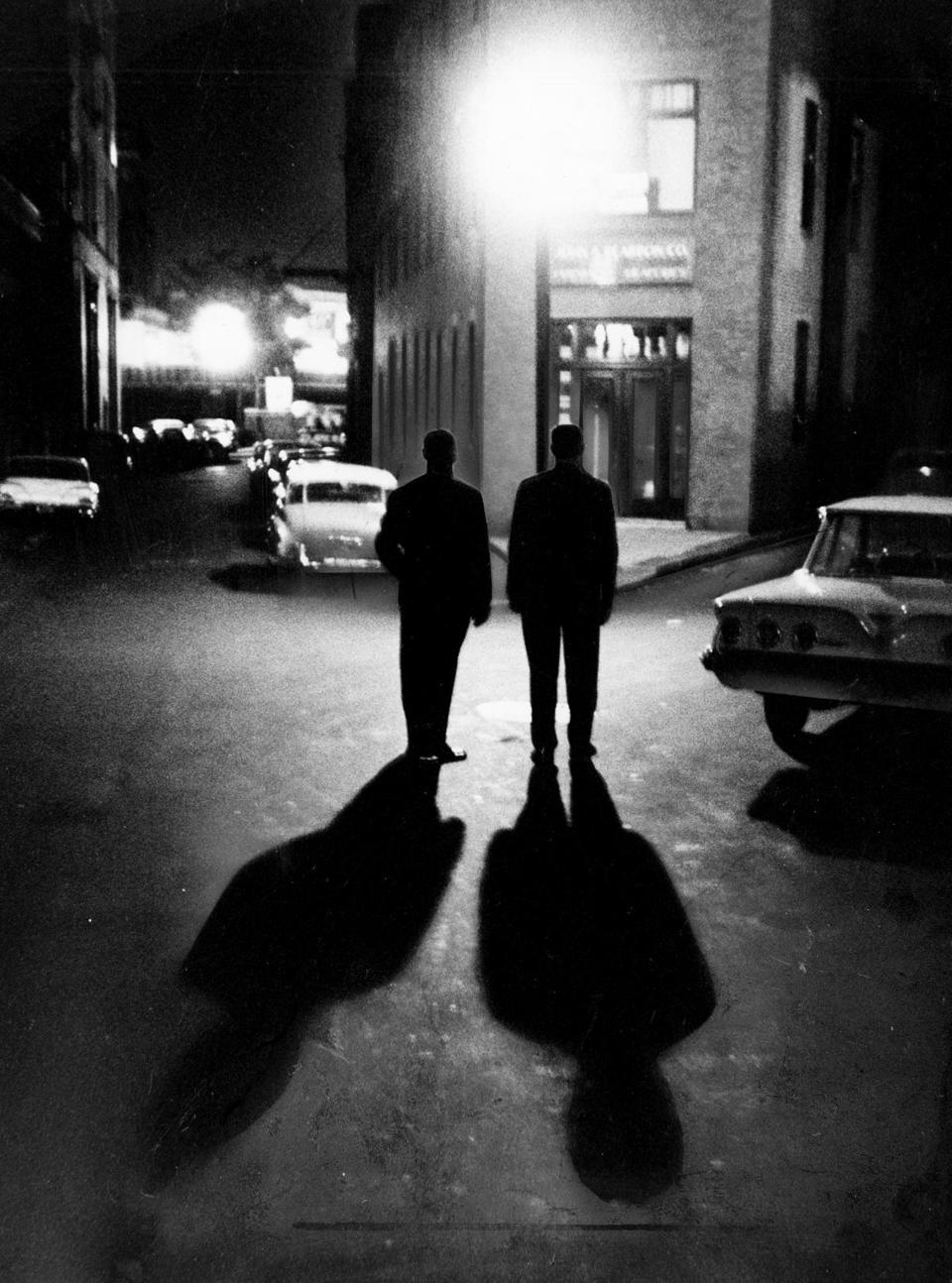

The Strangler unearthed

In the news today: Albert DeSalvo’s remains will be exhumed for DNA testing in one of the Boston Strangler murders. (Boston Globe story here, Times here.) DeSalvo confessed to thirteen murders, but his confession was riddled with contradictions and inconsistencies, and has always been doubted. Hard not to think of my own novel The Strangler. While researching then publicizing my book, many, many older Bostonians told me how vividly they recall the terror in the city during the Strangler panic.

Image: “Sept. 3, 1962: Boston police detectives worked through the night trying to solve the Strangler case after Jane Sullivan, 67, was discovered on Aug. 30, 1962, throttled to death in her apartment. She was believed to be the sixth victim….” Boston Globe.

Joan Acocella: Blocked

“Yesterday was my Birth Day,” Coleridge wrote in his notebook in 1804, when he was thirty-two. “So completely has a whole year passed, with scarcely the fruits of a month. —O Sorrow and Shame…. I have done nothing!”

In a 2004 piece in the New Yorker, Joan Acocella considers writers block. Why exactly do writers stop writing? (Pictured: Samuel Taylor Coleridge, one of the first known sufferers of writers block, a condition that does not seem to have existed, as such, before the early 19th century.)

Keats: “I was never afraid of failure”

It is as good as I had power to make it — by myself. Had I been nervous about its being a perfect piece, and with that view asked advice, and trembled over every page, it would not have been written; for it is not in my nature to fumble — I will write independently. — I have written independently without Judgment. I may write independently, and with Judgment, hereafter. The Genius of Poetry must work out its own salvation in a man: It cannot be matured by law and precept, but by sensation and watchfulness in itself — that which is creative must create itself — In Endymion, I leaped headlong into the sea, and thereby have become better acquainted with the Soundings, the quicksands, and the rocks, than if I had stayed upon the green shore, and piped a silly pipe, and took tea and comfortable advice. I was never afraid of failure; for I would sooner fail than not be among the greatest.

John Keats, in an 1818 letter to his publisher, responding to critics of his poem “Endymion” (punctuation as in original)

“It’s always difficult”

I work slowly; it’s always difficult — it’s nearly always difficult. I’ve been writing steadily, really, since I was twenty years old, and now I’m eighty-one. My routine now is to get up in the morning, have some coffee, start to write. And then a little later on, I might take a break and have something to eat and go on writing. The serious writing is done in the morning. I don’t think I can use a lot of time in the beginning; I maybe can only do about three hours. I do rewrite a lot, and I rewrite and then I think it’s all done, and I send it in. And then I want to rewrite it some more. Sometimes it seems to me that a couple of words are so important that I’ll ask for the book back so that I can put them in.

“Each book should be a new beginning”

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.

For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment. He should always try for something that has never been done or that others have tried and failed. Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed.

How simple the writing of literature would be if it were only necessary to write in another way what has been well written. It is because we have had such great writers in the past that a writer is driven far out past where he can go, out to where no one can help him.

Ernest Hemingway, 1954 Nobel Prize Speech