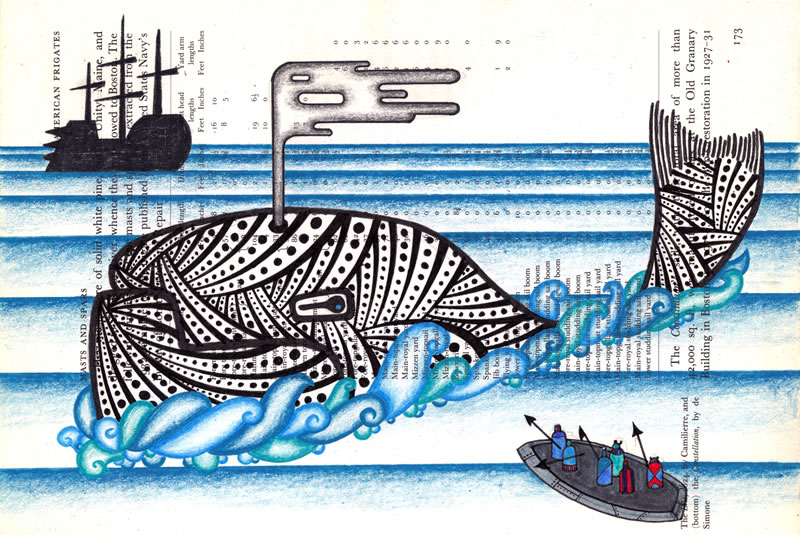

Matt Kish, whose bio says he is not an artist, is rereading Moby-Dick while creating a drawing for every page. I love this one, for page 109: “I will have no man in my boat,” said Starbuck, “who is not afraid of a whale.” (View full size here.) Details about the project are here, including an index of the drawings. For the record, Matt’s edition of Moby-Dick has 552 pages. Go, Matt! (via)

Matt Kish, whose bio says he is not an artist, is rereading Moby-Dick while creating a drawing for every page. I love this one, for page 109: “I will have no man in my boat,” said Starbuck, “who is not afraid of a whale.” (View full size here.) Details about the project are here, including an index of the drawings. For the record, Matt’s edition of Moby-Dick has 552 pages. Go, Matt! (via)

How Writers Write: Edwidge Danticat

Before she begins a novel, Edwidge Danticat creates a collage on a bulletin board in her office, tacking up photos she’s taken on trips to her native Haiti and images she clips from magazines ranging from Essence to National Geographic. Ms. Danticat, who works out of her home in Miami, says she adapted the technique from story boarding, which filmmakers use to map out scenes. “I like the tactile process. There’s something old-fashioned about it, but what we do is kind of old-fashioned,” she says.

Sometimes, the collage grows large enough to fill four bulletin boards. As the plot becomes clearer, she culls pictures and shrinks the visual map to a single board.

Right now, Ms. Danticat has two boards full of images depicting a seaside town in Haiti, the setting for a new novel that takes place in a village based on the one where her mother grew up.

She writes first drafts in flimsy blue exam notebooks that she orders from an online office supply store. She often uses 100 exam books for a draft. “The company I order from must think I’m a high school,” she said. She types the draft on the computer and begins revising and cutting.

Finally, she makes a tape recording of herself reading the entire novel aloud — a trick she learned from Walter Mosley — and revises passages that cause her to stumble.

— Alexandra Alter, “How to Write a Great Novel” (includes profiles of Junot Díaz, Colum McCann and many others)

The View from Below: A midlist author watches the ebook wars

This week, the battle over Amazon’s bid to corner the market on ebook sales — to establish itself as the iTunes of digital books — seemed to turn a corner. On one side, Amazon announced Steven Covey will abandon S&S to grant ebook rights to Amazon. On the other side, a consensus began to emerge in the publishing community that Amazon’s deep discounts on ebooks amount to predatory, possibly illegal monopoly-building — an effort to starve out its competitors. (You can read the gory details here, here, here, and here.)

In the end, I don’t think Amazon will succeed in becoming the iTunes of ebooks, not because Amazon is well-intentioned (it is not), but because it does not have the leverage. Apple was able to dominate digital music because of the iPod, which so clearly leapfrogged its competitors in terms of design, ease of use, and wide acceptance that it put Apple in position to dictate terms to its suppliers. It was hardware that won Apple its monopoly. Amazon has no such advantage. The Kindle is no iPod. To me, the Kindle seems primitive, clumsy, and ugly. It does some things well, but inevitably something better will come along, and soon, from a company with a better knack for design and technology. Smart phones may already be a better platform for reading ebooks. If nothing else, smart phones have the advantage of ubiquity: millions of people already have one in their pocket.

So I understand the publishing community’s hysteria over Amazon’s monopoly bid, but I don’t quite share it — not yet, anyway.

What I do not understand is the blithe, almost gleeful fatalism that tech geeks seem to feel about the struggles of traditional publishers to cope with the leap to digital.

Among the propeller heads, the prevailing view seems to be that Big Publishing is a horse-and-buggy business. Sudden technological change has rendered it irrelevant. All those editors and publicists in gaudy Manhattan offices — no longer needed. Ebook is to Big Publishing as asteroid was to dinosaur. Pity, but that’s the way it goes. End of story.

Certainly that’s the way it goes with web businesses. Amazon poleaxed the brick-and-mortar bookstores because it found a more efficient way to sell books. So if Amazon (or whoever) succeeds in cornering the ebook space, too, why sweat it? To the fastest, leanest, nimblest competitor go the spoils — and Lord knows, Big Publishing is none of those things.

To techies, it is all about maximizing efficiency. They wonder, What exactly do traditional publishing houses add to a writer’s work except cost — the added cost built into the price of every book to support this bloated, doomed, lumbering, inefficient, lazy, parasitic, contemptible industry? To them, Big Pub is precisely the sort of pathetic dinosaur the web specializes in obliterating.

Except that it’s not. Because publishers are not in the business people think they are, at least they are not only in that business. When people are asked what exactly it is that publishers do, the answers that usually come back are “gatekeeping” (filtering the publishable manuscripts from the dreck) and the various sub-tasks involved in manufacturing books (editing, book design, publicity, etc.). Those things are valuable, but if that was all traditional publishers did, I would say, Bring on the asteroid. There is probably more to be gained in the super-efficiencies of running the book business according to the ordinary Darwinian rules of the web. But those are not the most important things publishers do. Not even close.

What Big Publishing is, collectively, is a marketplace for new writing. Not a retail market like the one Amazon has created for ebooks, but an investment market, a futures market. Think of it as Silicon Valley for books, with every publisher a venture capitalist searching for the Next Big Thing.

VC’s invest in a portfolio of start-ups and nurture them through lean, money-losing years. The hope is that all will someday turn a profit and somewhere in that portfolio will be a breakout hit or two that justifies the whole risky endeavor. That is exactly how publishing houses invest in young writers. And like any good VC, Random House (or whoever) hedges its risk by investing in as many promising start-ups as it can find, betting that somewhere in its portfolio of young, talented, promising writers are a few that will break out and become hits.

Without this sort of start-up capital, there is no way an unproven writer could keep at it for long. I have never made a nickel for my publisher. Yet Random House continues to invest in me while I improve my writing, painstakingly build my readership, and grow my list of titles. At this point in my career, I need the help. So, like any entrepreneur, I trade off a lot of upside — the bulk of my royalties — in exchange for the money that enables me to build my business.

The question is, who will play the venture capitalist’s role if Amazon (or whoever) wins and books move to the iTunes model?

Consider Steven Covey and his new deal with Amazon. It may seem unfair that part of Covey’s earnings should go to pay for the stable of prospects on Simon & Schuster’s midlist. But it is only unfair in hindsight. S&S took a chance on Covey once by fronting him an advance. For all anyone knew, Covey might have ended up on the midlist himself, and S&S would be out the cash. In this case, it turned out to be a good bet. But Covey does not want to share the downstream profits. That makes perfect sense from Covey’s point of view, but does it make sense from ours, the reading public’s? (Yes, yes, I’m a self-interested member of the reading public. So what?)

Of course, we’ve already seen the iTunes model in action. Emerging young musicians in the brave new world of digital music can’t earn a living by recording anymore. They give away their MP3’s and survive by touring constantly (an option not open to writers: there is no market for our live performances, understandably).

So what? Life is tougher for young musicians. Should the public care? Well, has the quality or quantity of new, emerging musicians declined? I think so. The musicians may be out there, but you won’t find them on iTunes, not easily anyway. There is limited space on the landing page of the iTunes store, so most of those prime pixels go to established acts (today it’s Alicia Keys, Kesha, and an app for the movie “Avatar”). When there is only one record store in town and the store is that big, it’s awfully tough for a new band to get noticed. So, out on tour they go. And we music-buyers wind up listening to the same few bands over and over, often the same ones we’ve been listening to for years, or the ones anointed by Starbucks or American Idol as worthy of our attention. That is not a free or efficient market.

It is not clear how the iTunes model maps to book publishing. If there are fewer advances for emerging writers in an ebook world, will it make a difference? There will always be writers, after all. There always have been. There will always be a determined few willing to pay any price for their art, endure any hardship to keep writing. And a lucky few, an infinitesimal minority, will always be profitable right from the start. But the fact is, most writers need time to develop their talent and find their audience. Some percentage simply won’t be able to stick it out long enough. We can argue about how big that percentage might be, but we’d all be guessing. What we know for sure is that, without Big Publishing to act as patron, a lot of great books will never be written. Everybody okay with that?

Look, I don’t pretend to be objective about this. Obviously I have a stake in the current industry model. I’m one of those midlist guys still playing for time. So far, Random House, my publisher in the U.S., has stuck with me. They take their winnings from guys like Lee Child and bet it on a bunch of guys like me. If the current model breaks and writers have to scrape by as musicians do, who knows? Maybe I’ll make it, maybe I won’t. I have two kids. If push comes to shove, I’ll do what is in their interests, not mine. If that means doing something else, so be it. Maybe I have a great book in me, maybe I don’t. Maybe I’ll get the chance to find out, maybe I won’t. What matters is that there are a lot of writers like me, writers with potential who haven’t put it all together yet for one reason or another. Someday a few of us us will do it, a lucky few will come up with that Big Book — if we’re still writing.

That’s what’s at stake in Amazon’s big play this week.

Dickens vs. the Snarks

I am reading Dickens’s Little Dorrit at the moment, inspired by the rebroadcast of the wonderful PBS/BBC mini-series. (It is being rebroadcast here in Boston, at least. I don’t know if this is true elsewhere.)

At the same time I am spending endless hours, as usual, idling on the web, particularly on blogs, where a different aesthetic prevails — hyperbolic, sarcastic, terse, frantic, distracted. A recent blog post by Ben Casnocha defines the web prose style pretty well:

In school anything you write or do will be read and graded by a teacher paid to do so. In the real world nobody wants to read your shit, and you have to earn their attention every single day.

Last year in a post titled You Have to Make People Give a Shit, I extolled blogging as a way to learn this value.

One way blogging makes you a better writer is it forces you to work hard for your readers’ attention. On the web, it takes less than a second to close the page or click a new link. Your readers are busy and distracted.

This means you must engage the reader out of the gate and take nothing for granted. If you start sucking in the second paragraph, you’ll likely lose the reader’s attention. They click to a new page.

It’s brutal. It makes you better.

It certainly is brutal, but does it really make you better? Alternating between Dickens’s elegant slow-cooked style and the fast food of the web, as I’ve been doing this week, I’m not so sure. Here’s the thing: after snacking on blog after blog, link after link, article after article, I do not feel any of the satisfaction or pleasure or transport that I get from even the dullest passages in Little Dorrit. On the contrary, all that hyperlinked, hypermanic prose on the web leaves me feeling drained and a little down.

Maybe it is just the skittish nature of the medium. The very connectedness of every screenload of words to every other makes everything I read online feel provisional and slick. There is always another article quivering unseen behind every link, another article which may be more interesting or more fresh. And then another and another.

I don’t mean to knock Ben Casnocha. Actually, I agree with him: in the raucous atmosphere of the web, it is probably necessary to write as if “nobody wants to read your shit.” In fact, when I first started to think about this post, I intended to say something similar, that web writing is shaping today’s novels by training modern writers and readers alike in a more compressed, hurried, no-nonsense prose style. I still think that’s true.

But I’m not so sure it’s a good thing. When I turn off the computer (as I am about to do) and go back to the peaceful, unlinked, timeless world of Dickens’s London, it will be a relief. Dickens does not have to “make me give a shit.” I already do. I don’t want to feel “busy and distracted” while I’m reading, as I tend to feel when I’m reading online. And if Dickens starts to suck in the second paragraph, well, I’ve got time. What, after all, is the hurry?

Disconnect. Slow down. Read at your own pace, for your own pleasure. The web will get along without you for a while.

Publishing Agonistes

The major publishers are in a difficult position: they are service companies that function like manufacturing companies — 20th century businesses in a 21st century economy. The control of the book business is gradually slipping out of their hands.

— William Petrocelli, “No One Warned the Dinosaurs. Will Anyone Warn the Publishers?”

John Irving: “A need to be alone”

“I recognized at a pretty early age — certainly I was pre-teens — I noticed that the school day was enough of the day to spend with my friends. I seemed to have a need to … be alone.” I am sure this is a common characteristic of writers, even gregarious ones. Certainly I needed to have time alone as a kid, and I still do.

You can watch the full interview with John Irving here. Via Big Think.

Maugham: “great suspicion of posterity”

“I have great suspicion of posterity. I’m quite prepared to be entirely forgotten five years after my death.”

“Tamburlaine Must Die”

Louise Welsh’s Tamburlaine Must Die is a short, atmospheric, brisk novella to be consumed in a single sitting. It is the story of the final days of the Elizabethan poet Christopher Marlowe, whose murder in 1593 is one of the great unsolved historical mysteries beloved by conspiracy theorists. (Google it, you’ll see.) The book is narrated by Marlowe himself in the form of a final written testimony dashed off on the eve of his murder, which he fully anticipates.

In Welsh’s version of events, someone has pasted a blasphemous poem to the door of a church and signed it “Tamburlaine,” a character from Marlowe’s most famous play. Now, with rumors flying that Marlowe himself is the heretic, he has just a few days to find the real “Tamburlaine” or face the gruesome death of an apostate in the religious police state that was Elizabethan England, to be hung, drawn and quartered before a bloodthirsty mob.

At barely 140 liberally spaced pages, Tamburlaine Must Die is too short to work as a mystery. There just isn’t enough space for Welsh to fill in the details of the many intricate, shadowy conspiracies she hints at. The story rushes along too quickly to get bogged down in perfunctory details of who, what, where, why. The dramatic question of the book is Who killed Christopher Marlowe? Welsh’s somewhat unsatisfying answer: Who knows?

Or, more exactly, Who cares? Welsh is not interested in telling a suspenseful man-on-the-run mystery. Her Marlowe is not Jason Bourne in period drag, so she can afford to slight the usual devices of thriller novels. What engages Welsh is not Marlowe’s death but his world.

And when she describes the streets and people of London in 1593, the book soars. Here is the crowd at a public execution:

Wild-eyed masks, red-faced and spittle spattering, some with appetites so awakened they stuff themselves with pies, meat juices glossing their chins, pastry cramming their mouths, even as they call for the coward to be cut down and quartered.

In the streets we meet “muscle-armed” milkmaids and a “skelfy” jailer whose skin has “the transparent gleam of a white slug.” The agents of the police state are everywhere, spies and informers, torturers, inquisitors. One is always a careless word away from a shiv to the gut or, worse, the Tower and the rack. It is a vivid, menacing dystopia that reminded me of Philip Kerr’s Berlin trilogy, even of Orwell’s 1984.

Violence seems to sharpen Louise Welsh’s prose, a vice I share with her and thoroughly approve. We share other things, too. I won a prize once for my first novel that Welsh had won the year before, both for gritty crime novels set in our home towns, Glasgow for Welsh, Boston for me. For our second novels we both chose famous unsolved murders in fairly accurate historical settings. Why? Maybe the escape into the pseudo-reality of historical fiction frees the imagination from the pressure to duplicate an early success, or deflects the expectation that you will continue to represent your city “authentically” in book after book — to become some sort of arch Glaswegian or Bostonian. In choosing Marlowe’s London for her second novel, Welsh traveled further from home than I did. It was a pleasure for a couple of hours to go there with her.