It has been reviewed everywhere already, so I won’t blather on about it. But Matterhorn by Karl Marlantes is great. Original, authentic, and heartfelt. Highly recommended.

Bloggiversary

Yesterday was the first anniversary of this blog, which went up on May 22, 2009. As I’ve written here before, I doubt that the blog will generate significant book sales, which was why I started doing it, but I’ve come to enjoy blogging for its own sake and I’ve made a few new friends in the bargain. I may never get to that mythical thousand true fans, but if you’re a writer, you write — even if it’s not clear how many people are reading.

Anyway, here are a few random statistics about this blog’s first year. They are culled from SiteMeter, which is linked at the bottom of every page (click the green badge in the footer), and WordPress itself, the software the site runs on, which compiles a slightly different array of stats.

- Total visits: 8,547. Total page views: 14,946. Those are infinitesimal numbers next to some of the bigger blogs out there, but they are much higher than I expected a year ago. (The SiteMeter badge in the footer of this page understates the visits count because I did not join SiteMeter until a couple of months after the blog launched.)

- Most views in one day: 180. A spike like that usually means a post got picked up by some high-visibility blog or Twitterer.

- Average views per day: 41.

- Total posts: 150 (not including this one).

- Most Popular post: 848 hits, for a post on the writing habits of Graham Greene. The popularity of this post points up the difficulty of winning fans to my books by blogging. Most people come to this blog after Googling something completely unrelated to me but that I happen to have written about, like Graham Greene. Most of these visitors don’t stick around to learn about my books. Some of them do, I suppose, but it is a vanishingly small number. So is it worth it? Damned if I know.

- Least popular posts: 1 hit. Eight posts are tied for this honor. And I can’t even be sure that the one lonely hit isn’t me checking to see that the post looks all right. I don’t do much to publicize this blog. I link to significant new posts on Twitter and Facebook, but most of the smaller stuff I just put on the blog and never alert anyone. So most of the short posts slip under the radar, which is fine. Anyway, I will award the honor for Least Popular Post to this one, in which I announced I was taking a vacation and inexplicably required three long paragraphs to do it. It cops the prize because of this pathetic irony: a post announcing there will be nothing to read — and nobody bothered to read it. Oy. Blogging can be a kick in the groin.

- Total comments: 259. The best part of blogging by far is hearing from readers.

- Total cost: $0. Well, this isn’t quite true. I do pay to have the site hosted at Media Temple. But the site itself has cost me nothing. All the software and services I use are free. All the design, the Photoshopping, the coding, and of course all the writing is done by me. Of course, all that labor is only “free” if you assume my time has no value…

Last thing: the map below, also clipped from SiteMeter where you can see an updated interactive version anytime, shows the location of the last hundred visitors. In the last two days or so, this blog has had visitors from Queensland, Australia; Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong and New Delhi; Israel, Ukraine, Spain, France, Holland, Belgium, plus several in England; and all over the U.S. Very cool.

Writing Like It’s 1999

John Dvorak had an interesting piece recently on the transformation of computers “from being a mathematical tool used for calculations, to a communications device.”

Initially, computers were used for calculations. The first intended purpose was for artillery trajectory calculations — hardly a noble purpose, but certainly a practical one. In the early days, computers were described as electronic bins. … As the desktop computer revolution developed, the devices’ uses were inevitably based on some aspect of calculation. Spreadsheets were the perfect example. At the time, the only communication aspect of computers was the fact that they could double as powerful aids to word processing software.

By 1979, however, modems and networks were making inroads. They made it possible for computers to talk to each other in some crude way. That was the beginning of the end. The computation aspect of computers continued to grow, but it was the networking aspect that was the disease vector, so far as social upheaval is concerned. You can figure out the rest of the networking timeline. It began 30 or more years ago — 40 years, if you want to count the invention of Arpanet in 1969.

The iPad and smart phones are just the logical conclusion to this trend: computers whose only real purpose is to communicate, not calculate.

Whatever the grand social implications of “the communications-oriented computer” — Dvorak considers it an asocial, porn-proliferating, newspaper-killing “disease” — it has been a disaster for writers, at least for this highly distractible writer.

I’m no Luddite. I love the web, maybe too much. Most evenings now, after my kids go to bed, I find myself opening up a laptop and reading online when once I would have opened a book or turned on the TV. To a natural reader, it is like heaven — an endless library. (Also an endless TV and jukebox, but personally these aspects interest me less.)

That is just the problem: the web is a massive distraction that is becoming increasingly difficult to tune out. Today you can’t buy a new laptop that is not wifi-enabled, and you can’t walk into a library or Starbucks that does not provide wifi. No doubt computers eventually will follow smart phones into a world where all computers are connected to the web all the time, with or without wifi.

The irony is that today’s computers are actually less useful for writers than were the slower, “dumber,” un-networked boxes of ten years ago. That is because writers need to do the one thing modern computers can’t — disconnect.

I hear the objection already. “Why don’t you just turn off the damn internet for a while? Close your browser. Show some willpower, some discipline!”

Well, that is what most writers do. What choice is there? But over and over I hear writers echo my own experience, which is that the web is very difficult to block out entirely, because the same machine we use for typing is also the one we use for web-surfing. Our work tool has become a play tool. Our typewriter has become a TV. What you scolds may not understand is that our work is different from yours. Writing of any quality requires deep focus; long, quiet, undisturbed stretches of time; and isolation — in Joyce’s famous phrase, “silence, exile, and cunning.” Any work that involves serious thought requires some of these things some of the time, I suppose, but good writing needs them all, every day. And modern computers, alas, are designed to create the opposite environment: distraction, connection, zoning out.

What we writers need is a computer optimized for word processing and nothing else. A “dumb” computer that is little more than a “smart” typewriter. A workspace — a computer screen — with no distractions, that does not tempt us to pop online “just for a minute to check email.”

I have found something close in the AlphaSmart Neo, a simple plain-text word processor with virtually endless battery life, whose praises I have sung before. But once I have completed a draft of a novel and moved to the editing phase, I have to use a word processing program, in my case WordPerfect, to which I am passionately, stubbornly devoted. That means I have to switch to a laptop.

So how do I work on a laptop and completely shut out the web? By eliminating all the “advances” of the last decade.

I recently bought an old ThinkPad T23 on eBay. The laptop was made in 2001 or thereabouts. It was a high-end machine at the time, with a retail price well north of $3,000, but I picked mine up for about a hundred bucks. The build quality of these old ThinkPads is unsurpassed, and the T23 is engineered to be light and tough enough for corporate road-warrior types. It has a great keyboard but, honestly, not much else. Best of all, it has no wireless card.

A nine-year-old laptop is not a perfect solution, of course. Battery life is short (I get about 1:45). At 5.5 pounds the T23 weighs a little more than today’s ultraportables. And with such an old machine, who can say how much tread is left on the tires? But so far I am thrilled. To a writer, less is more. I bought this computer precisely for what it can’t do.

I wonder: isn’t there enough of a niche market to support a new laptop like this, which sacrifices processing power, memory, and networking ability for the simpler things that writers and other thinkers value — low price, long battery life, light weight, good keyboard, bright screen? The ideal writer’s computer would have many of the virtues of a netbook, minus the connectivity, plus a little size to accommodate a better keyboard and display. It would be good for students, too. Certainly it would be a machine John Dvorak would love.

The Murder Gene

Last September in Italy, a man convicted of what would, in this country, be called second-degree murder or manslaughter had his 9-year sentence reduced on appeal on the grounds that he exhibited

abnormalities in brain-imaging scans and in five genes that have been linked to violent behaviour — including the gene encoding the neurotransmitter-metabolizing enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA). … Giving his verdict, [the judge] said he had found the MAOA evidence particularly compelling.

The ruling marks the first time a defense based on behavioral genetics — the argument that a defendant’s genes caused him to commit the crime — has affected the outcome of a criminal case in any European court. To my knowledge, no defendant has ever succeeded with this argument in America, either, though many have tried.

I have written before about the implications of behavioral genetics for criminal law, which is built on the assumption that we are generally responsible for our own actions. Surely this is an issue the criminal courts will have to face: some people may indeed be genetically hard-wired for violence. But this decision comes as a surprise to me because the science does not seem to justify it, not yet. We simply don’t know that a single gene like MAOA causes specific behaviors, even in very specific gene-environment interactions. It is a bad decision but a telling one: as the science of behavioral genetics advances, at some point the courts will find it impossible ignore. (To learn more, a great scholarly article by law professor Owen D. Jones is here.)

For now, though, the idea of a “murder gene” is the stuff of novels, not science. My own next novel takes up this very issue. It involves a man named Andy Barber, who descends from a long line of violent men and whose teenage son Jacob is accused of murdering a classmate. Jacob, it turns out, also carries the MAOA gene variant — sometimes called the “warrior gene.” Preparing for his son’s murder trial, Andy says,

The legal question we discussed most … was the relevance of Jacob’s violent bloodline. We referred to this issue as the “murder gene” to express our contempt for the idea, for its backwardness, for the way it warped the real science of DNA and the genetic component of behavior, and overlaid it with the junk science of sleazy lawyers, the cynical science-lite language whose actual purpose was to manipulate juries, to fool them with the sheen of scientific certainty. The murder gene was a lie. It was also a deeply subversive idea. It undercut the whole premise of the criminal law. In court, the thing we punish is the criminal intention — the mens rea, the guilty mind. There is an ancient rule: actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea — “the act does not create guilt unless the mind is also guilty.” This is why we do not convict children, drunks, and schizophrenics: they are incapable of deciding to commit their crimes, not with a true understanding of the significance of their actions. Free will is as important to the law as it is to religion or any other code of morality. We do not punish the leopard for its wildness. But that is the argument Logiudice [the prosecutor] would make if he had the chance: born bad. He would whisper it in the jury’s ear, like a gossip passing a secret. We were determined to stop him, to give Jacob a fair chance.

The murder gene may indeed be junk science, for now at least, but it is a haunting idea. We are quite comfortable with the idea that certain benign traits may inherited — musical talent, athleticism. Why not a talent for violence?

Image: Bryan Christie, “Pharmaceutical Brain”

The Mystery Writer’s Dilemma

“Hugger-mugger takes a lot of explaining, a lot of diagramming. An additional trouble with it, which keeps the suspense thriller, however skillful and polished, a subgenre, is that the novelist, manipulating his human counters on the board, must keep them somewhat blank, with selective disclosure of their inner lives, lest the killer or mole or whatever be prematurely unmasked.”

— John Updike, “Hugger-Mugger”, The New Yorker, 9.18.06, reviewing le Carré’s novel The Mission Song.

The more you know about a character, the less mystery remains. The less you know about a character, the less believably human he seems. In technical terms, literature requires “round” characters, mystery requires “flat” ones. The trick is to square that circle somehow.

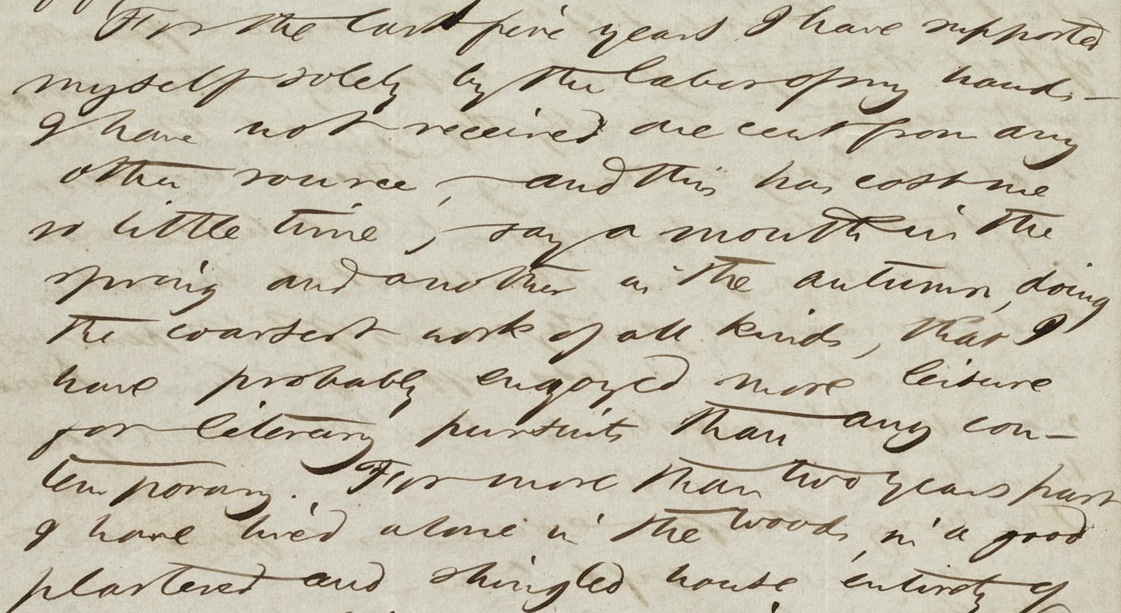

“I have lived alone in the woods”

The Boston Public Library in Copley Square, where I often go to write, is running an amazing year-long exhibition called “Cool + Collected: Treasures of the BPL” which highlights some of the rare holdings in the library’s collection. The contents of the exhibit rotate every few months, and the current crop is truly remarkable. It includes original handwritten letters by Louisa May Alcott, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Frederick Douglass, and others. It is a hall of fame of American letters! My favorites are an original working draft of a poem by Walt Whitman, with edits literally cut and pasted on the page, and a four-page letter from Henry David Thoreau to Horace Greeley which begins:

Concord May 19th 1848.

My Friend Greeley,

I received from you fifty dollars today. —

For the last five years I have supported myself solely by the labors of my hands — I have not received one cent from any other source, and this has cost me so little time, say a month in the spring and another in the autumn, doing the coarsest work of all kinds, that I have probably enjoyed more leisure for literary pursuits than any contemporary. For more than two years past I have lived alone in the woods, in a good plastered and shingled house entirely of my own building, earning only what I wanted, and sticking to my proper work. The fact is man need not live by the sweat of his brow — unless he sweats easier than I do — he needs so little. For two years and two months all my expenses have amounted to but 27 cents a week, and I have fared gloriously in all respects. If a man must have money, and he needs but the smallest amount, the true and independent way to earn it is by day-labor with his hands at a dollar a day. — I have tried many ways and can speak from experience. — Scholars are apt to think themselves privileged to complain as if their lot was a peculiarly hard one. How much have we heard about the attainment of knowledge under difficulties of poets starving in garrets — depending on the patronage of the wealthy — and finally dying mad. It is time that men sang another song. There is no reason why the scholar who professes to be a little wiser than the mass of men, should not do his work in the ditch occasionally, and by means of his superior wisdom make much less suffice for him. A wise man will not be unfortunate. How then would you know but he was a fool?

The letter ends, “P. S . My book” — Walden, presumably — “is swelling again under my hands, but as soon as I have leisure I shall see to those shorter articles. So, look out.” (You can read a transcript of the rest of the letter here.)

The exhibit has other wonderful things, too, posters and prints and rare books and so on. But to me — to any writer or reader, I bet — to see the actual handwriting of these giants of American letters is to feel their presence. The experience is electric.

If you’re around Copley Square, check it out (through June). If not, the whole exhibit is available online, in glorious high resolution, on Flickr. Lord knows what else the BPL has stashed away in the vault. Very cool indeed.

A Male Jodi Picoult

Yesterday my novel-in-progress reached a critical milestone. My editor and I had a long talk in which we agreed that the story is now all in place. A new ending, which takes the story in a direction I never dreamed of when I began writing page 1, now seems right and credible, even inevitable — in the way that good endings always seem inevitable once you have “discovered” them. So what remains now is just minor changes, polishing. In 2-4 weeks I will turn the manuscript in and essentially be done with it. There will be a few more rounds of edits, but from here on the changes will be increasingly picayune, things like moving commas and checking for internal consistency. Important, yes, but less arduous.

The feedback from my editor, Kate Miciak, has been glowing. Kate is a brilliant editor and not one to bullshit. Lord knows, she has been blunt about my manuscripts in the past. So when she raves, I take her at her word. And she is raving about this book.

The hope is that the book will appeal to a wider audience than my first two have. It is not a gritty urban crime story. The setting (the suburbs) and the characters seem more “relatable.” It should be more accessible to the wide swath of readers who, to be frank, I will have to reach if I am to make a go of this: women, book clubs, general-fiction readers who simply won’t consider genre mystery or suspense, no matter how literate or rich. Not to worry: the book is a crime story. But it is equally a family story and a lot less bloody than my other novels have been. I know, I know — I’m getting old, going soft.

A few other random developments:

- The book still does not have a title. This has bugged me from the start, as I’ve written here before. A title brings the whole project into focus. A book without a title is like a forgotten name — it is right on the tip of your tongue but you can’t quite find the words. Infuriating.

- I hope to “publish” the first chapter online very soon. I’d love to share at least a little bit of the story with readers who have been waiting for a long time already and now will have to wait until next summer. Obviously this raises copyright issues but I can’t imagine Bantam will object. They routinely publish the first chapter of upcoming books as a teaser. Stay tuned.

- The last couple of weeks have been a root canal. I lost energy and focus. Attention fatigue set in; I have been staring at this project too damn long. Worse, I had just expended quite a bit of energy to get the manuscript in, only to be told the ending needed a complete rewrite. So maybe a letdown was inevitable. Still, this was a lowpoint. That’s the way it goes, though. Writing a novel is a marathon. There are lots of ups and downs like this. Now, at least, I am over Heartbreak Hill and racing for the finish. Now run, you lazy bastard, run!

- The book will be a lead title for Bantam in spring or summer 2011. The precise pub date has not been set yet and won’t be for quite some time. As all publishers do, we will look for a window when no bigfoot authors are rolling out their summer blockbusters. It’s hard enough to generate buzz during the lulls.

- My editor envisions a hardcover-to-trade-paperback path for the book. That is a big step for me, one I am very excited about. I have always felt that my books are miscast as mass-market paperbacks, and I have always wanted to see them in trade format. (Trade paperbacks are the larger size, priced around $12-$15. The format signals readers that the publisher considers the book a significant one, worthy of the higher price even for a paperback.) There has been some category confusion about my books, I’m afraid. They look for all the world like airport thrillers but they read like something else. What that “something else” is, exactly, is anybody’s guess. “Literary crime”? Good luck finding that section in your local bookstore. Unfortunately, there is no precise pigeonhole for me in the market, which is why my books have been tough for publishers to position. But trade paperback gets closer to the mark.

- It has been suggested that this book might become a template for me and, rather than pursue more violent tales of urban mayhem, I might just settle down and become “a male Jodi Picoult, with a touch of Scott Turow.” Which sounds just grand to me.

Finally, thank you, sincerely, to everyone who reads this blog and sends emails and “likes” me on Facebook and waits around for years between books. You readers mean the world to me. It is a privilege to be a novelist. You all make that possible. I never forget that.

New Money

Designer Michael Tyznik’s concept for a redesign of American currency (rejected, of course).