Olivia Fox on the impostor syndrome, innovation, and “failing successfully.” Shorter version here. Via.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle … Live

Playwright Bill Doncaster emailed the following press release the other day. I’ve already gushed about Eddie Coyle enough on this blog, both the novel and the film, so you will not be surprised to hear that this sounds incredibly cool to me. I’ll be at the Burren to see it. You should be, too.

George V. Higgins’ The Friends of Eddie Coyle… LIVE

Staged reading, Saturday, Nov. 13, 3 p.m. The Burren, Davis Square, Free

SOMERVILLE – Widely regarded as the greatest Boston crime novel ever written, a staged reading of a new theatrical adaptation of George V. Higgins’ The Friends of Eddie Coyle will be performed at The Burren, Somerville, on Nov. 13 at 3 p.m.

Adapted for the stage by Bill Doncaster, directed by Maria Silvaggi, The Friends of Eddie Coyle chronicles the lowest rungs of the criminal underworld, as Eddie Coyle attempts to stay alive and out of jail in the company of gun runners, bank robbers, hit men and cops in and around 1970 Boston. Critically acclaimed since its release in 1972, Elmore Leonard called The Friends of Eddie Coyle “The best crime novel ever written — makes The Maltese Falcon read like Nancy Drew.”

This staged reading is free, donations for the cast will be graciously accepted, rsvp required: afriendofeddie@gmail.com.

The cast includes Paulo Branco as Eddie Coyle, Rick Park as Dillon, Tom Berry as Dave Foley, Peter Darrigo as Jimmy Scalisi, Jason Lambert as Jackie Brown, Jen Alison Lewis as Wanda, and featuring Jim Barton, Derrick Martin, Courtney Miranda, and Jeremy Lee.

The Cure for Procrastination

Before you sweat the logistics of focus: first, care. Care intensely.… Obsessing over the slipperiness of focus, bemoaning the volume of those devil “distractions,” and constantly reassessing which shiny new “system” might make your life suddenly seem more sensible — these are all terrifically useful warning flares that you may be suffering from a deeper, more fundamental problem…. Know in your heart that what you’re making or doing matters… First, care. Then, as you’ll happily and unavoidably discover, all that “focus” business has a peculiar way of taking care of itself.

Drawing Circles

The other day I blogged about the story of Giotto’s O: A messenger from the Pope arrived in Giotto’s studio in Florence one morning. He asked for a drawing to prove the artist’s skill to the Pope, who was seeking a painter for some frescoes in St. Peter’s. As Vasari tells the story, Giotto “immediately took a sheet of paper, and with a pen dipped in red, fixing his arm firmly against his side to make a compass of it, with a turn of his hand he made a circle so perfect that it was a marvel to see it.” Of course, Giotto got the job.

I had never heard the story until I ran across it online recently. It stuck in my mind, a romantic parable of what artistic mastery means. To paint an angel, first you must learn to paint a perfect circle — something like that.

Curious, I wandered around the web looking for more information about Giotto and his circle, and, in the hopscotch way of the web, I found an interesting blog post that linked Giotto’s O to a different sort of circle, the ensō, the asymmetric circle of Japanese Zen calligraphy.

In Zen Buddhist painting, ensō symbolizes a moment when the mind is free to simply let the body/spirit create. The brushed ink of the circle is usually done on silk or rice paper in one movement (but the great Bankei used two strokes sometimes) and there is no possibility of modification: it shows the expressive movement of the spirit at that time. [Wikipedia]

The imperfection of the circle — the asymmetry, the visible brush trails, the blobs of ink — is the point. In its very “flaws,” ensō embodies a traditional Japanese aesthetic, fukinsei (不均整), asymmetry or irregularity. Garr Reynolds (one of my favorite bloggers) explains,

The idea of controlling balance in a composition via irregularity and asymmetry is a central tenet of the Zen aesthetic. The enso … is often drawn as an incomplete circle, symbolizing the imperfection that is part of existence.

So these two famous circles, Giotto’s O and the ensō, embody very different aesthetic ideals.

Giotto’s circle is precise mechanical perfection, “a circle so perfect that it was a marvel to see.” Even his technique is machinelike: he pins his elbow to his side, turning his arm into a virtual compass.

Vasari adds another detail, as well. In the versions of the story that I initially read, Giotto loads his brush with red paint and paints the circle with a single sweep of his arm. But in Vasari’s telling, Giotto scratches out his circle with a pen (a quill, presumably) rather than a brush. He wants to eliminate even the wavering edge of a brush stroke, the little quivers of the bent bristles.

In writing, that sort of perfectionism is fatal. The very idea of creating “perfect” sentences or stories is paralyzing. No one can write perfectly. I have learned this lesson the hard way. I am a perfectionist by nature. It is no wonder the Giotto story appealed to me. But there are no Giottos in writing. You have to embrace imperfection, you have to accept the little oddities and surprises that emerge in the moment of creation, in the immersive “flow” state that characterizes the best writing sessions. I don’t know the first thing about Zen, but to me the go-with-it philosophy of the ensō feels much truer to the actual experience of writing well. It is not a feeling of abandon; like ensō painting, good writing is never careless or out of control. At the same time, every writer has to accept the little wobbles of his brush, the little traces of his bristles, the funny pear-shape of his ensō. Not because these flaws are unavoidable (though they are) but because they are beautiful.

To a writer like me — who tends to self-edit too much, who sometimes imagines he can write perfectly — the story of Giotto’s O teaches the wrong lesson. I will think of the ensō instead.

James Surowiecki: Later

A theory of procrastination:

“… the person who makes plans and the person who fails to carry them out are not really the same person: they’re different parts of what the game theorist Thomas Schelling called ‘the divided self.’ Schelling proposes that we think of ourselves not as unified selves but as different beings, jostling, contending, and bargaining for control.… The idea of the divided self, though discomfiting to some, can be liberating in practical terms, because it encourages you to stop thinking about procrastination as something you can beat by just trying harder. Instead, we should rely on what Joseph Heath and Joel Anderson, in their essay in The Thief of Time, call ‘the extended will’ — external tools and techniques to help the parts of our selves that want to work. A classic illustration of the extended will at work is Ulysses’ decision to have his men bind him to the mast of his ship. Ulysses knows that when he hears the Sirens he will be too weak to resist steering the ship onto the rocks in pursuit of them, so he has his men bind him, thereby forcing him to adhere to his long-term aims.”

Anybody got a mast I can borrow for the next couple of weeks?

San Francisco, 1906

Aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire (via)

The origin of “I coulda been a contender”

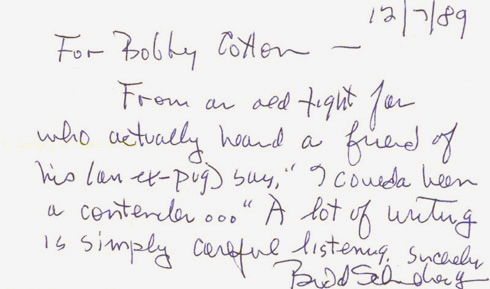

A note from screenwriter Budd Schulberg to a fan, jotted on the back of an index card, explains the origin of the famous line from “On the Waterfront.” The note reads:

12/7/89

For Bobby Cotton —

From an old fight fan who actually heard a friend of his (an ex-pug) say, “I coulda been a contender…” A lot of writing is simply careful listening.

Sincerely,

Budd Schulberg

Now, about that one-way ticket to Palookaville…