Book trailer for the upcoming release of Defending Jacob in France (Défendre Jacob, available October 11 from Éditions Michel Lafon).

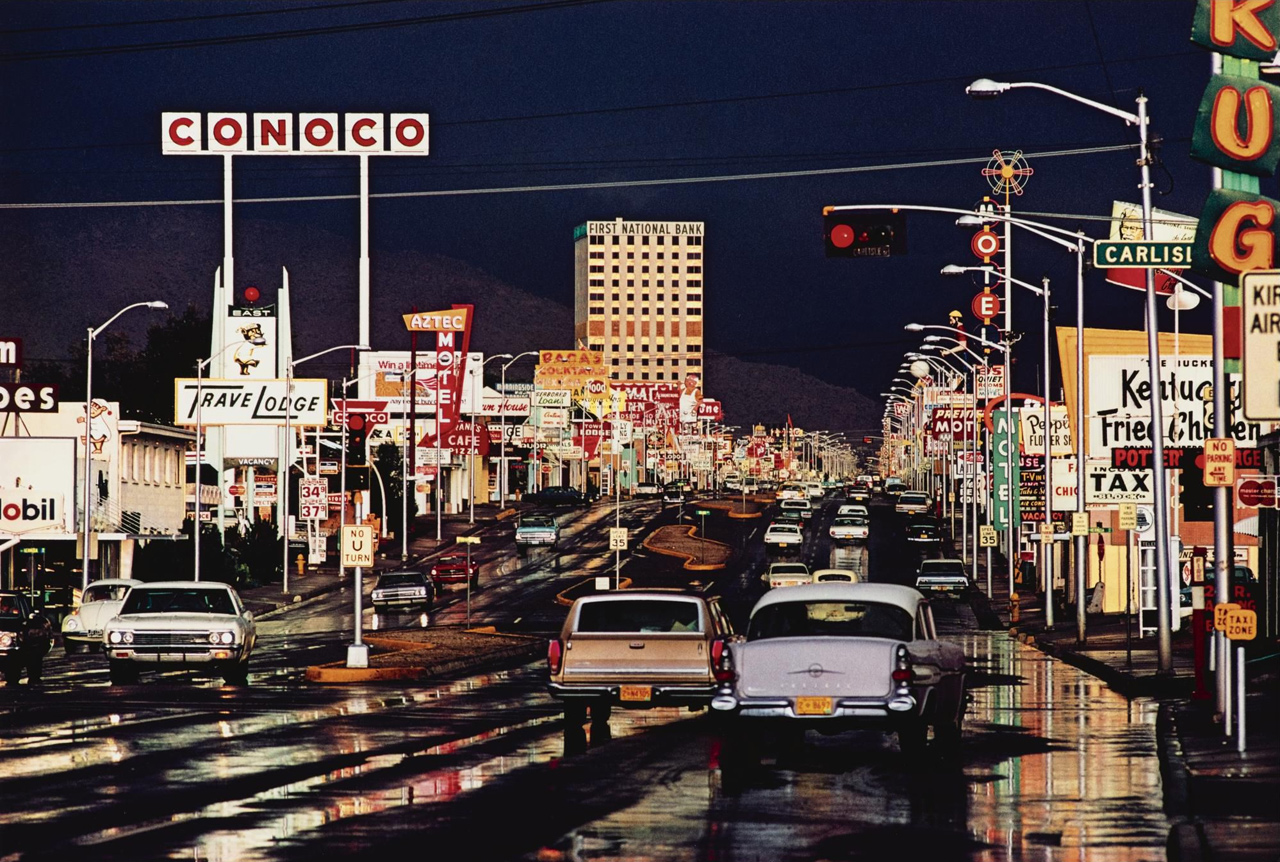

Route 66, 1969

Ernst Haas, “Route 66, Albuquerque, New Mexico” (1969)

Emerson: Finish each day and be done with it

Finish each day and be done with it. You have done what you could. Some blunders and absurdities have crept in; forget them as soon as you can. Tomorrow is a new day, you shall begin it serenely with too high a spirit to be encumbered by your old nonsense.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Homer votes

Demolition of Boston’s West End

Chambers and Barton Streets, July 19, 1959 (via).

Zadie Smith’s Ten Rules for Writers

- When still a child, make sure you read a lot of books. Spend more time doing this than anything else.

- When an adult, try to read your own work as a stranger would read it, or even better, as an enemy would.

- Don’t romanticise your “vocation.” You can either write good sentences or you can’t. There is no “writer’s lifestyle.” All that matters is what you leave on the page.

- Avoid your weaknesses. But do this without telling yourself that the things you can’t do aren’t worth doing. Don’t mask self-doubt with contempt.

- Leave a decent space of time between writing something and editing it.

- Avoid cliques, gangs, groups. The presence of a crowd won’t make your writing any better than it is.

- Work on a computer that is disconnected from the internet.

- Protect the time and space in which you write. Keep everybody away from it, even the people who are most important to you.

- Don’t confuse honours with achievement.

- Tell the truth through whichever veil comes to hand — but tell it. Resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied.

Zadie Smith (via)

Antietam, 1862

Alexander Gardner, “A lone grave on the Antietam battlefield” (1862) (via Slate)

Tchaikovsky: Work without inspiration

Do not believe those who try to persuade you that composition is only a cold exercise of the intellect. The only music capable of moving and touching us is that which flows from the depths of a composer’s soul when he is stirred by inspiration. There is no doubt that even the greatest musical geniuses have sometimes worked without inspiration. This guest does not always respond to the first invitation. We must always work, and a self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood. If we wait for the mood, without endeavouring to meet it half-way, we easily become indolent and apathetic. We must be patient, and believe that inspiration will come to those who can master their disinclination.

A few days ago I told you I was working every day without any real inspiration. Had I given way to my disinclination, undoubtedly I should have drifted into a long period of idleness. But my patience and faith did not fail me, and today I felt that inexplicable glow of inspiration of which I told you; thanks to which I know beforehand that whatever I write today will have the power to make an impression and to touch the hearts of those who hear it. I hope you will not think I am indulging in self-laudation if I tell you that I very seldom suffer from this disinclination to work. I believe the reason for this is that I am naturally patient. I have learnt to master myself, and I am glad I have not followed in the steps of some of my Russian colleagues, who have no self-confidence and are so impatient that at the least difficulty they are ready to throw up the sponge. This is why, in spite of great gifts, they accomplish so little, and that in an amateur way.

Pyotr Tchaikovsky, letter to a benefactor, 1878 (via Brain Pickings)