What little I’ve accomplished has been by the most laborious and uphill work, and I wish now I’d never relaxed or looked back — but said at the end of The Great Gatsby: “I’ve found my line — from now on this comes first. This is my immediate duty — without this I am nothing.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Archives for 2023

Shakespeare as he intended it to sound

Years ago, on a trip to England, I visited the Globe Theatre where an actor recited Shakespeare’s words in their original pronunciation. Until then, I had no idea how different the same words sounded in Shakespeare’s time. Remarkable. (Via Kottke.)

Scenius

There’s a healthier way of thinking about creativity that the musician Brian Eno refers to as “scenius.” Under this model, great ideas are often birthed by a group of creative individuals — artists, curators, thinkers, theorists, and other tastemakers — who make up an “ecology of talent.” If you look back closely at history, many of the people who we think of as lone geniuses were actually part of “a whole scene of people who were supporting each other, looking at each other’s work, copying from each other, stealing ideas, and contributing ideas.” Scenius doesn’t take away from the achievements of those great individuals: it just acknowledges that good work isn’t created in a vacuum, and that creativity is always, in some sense, a collaboration, the result of a mind connected to other minds.

— Austin Kleon (via Kottke)

Ian McEwan on creating characters

It’s something like a person walking toward you through a mist: Every sentence you write about her makes her a little clearer.

Jacob Begins

Recently I updated this website to a more modern design. That required a review (still ongoing) of a lot of old blog posts whose format was not compatible with the new code. In the course of rummaging around in all that old material (the blog dates to May 2009), I came across this little article that I published on Esquire magazine’s website in 2007. It was part of a series called “The Last Line.” I had completely forgotten the piece. In it, I discuss the novel that, years later, would become Defending Jacob. Interesting how much I knew early on and also how little. Novel writing is a journey; here I am taking the first steps.

Fathers and Sons. (And Murder.)

Our question: “What is the last sentence you wrote and why?” Master of suspense William Landay answers and still manages to keep us guessing. (Published: Jul 31, 2007)

“I don’t know what I expected to find, blood stains or some such, but there was none of that.”

Why he wrote the last line: This line is from a first draft of a novel I’m working on. The story is told by Andy Lewis, a father approaching middle age, an ordinary suburban guy whose son is accused of that most extraordinary crime, murder. The son does not deny the murder but claims self-defense. In this scene, Andy, who happens to be a prosecutor, has wandered to the scene of the murder, alone, ostensibly to look for evidence.

That he finds none is important to me. It announces that this is not going to be another CSI-style mystery. The story will not turn on the arcana of forensic science. (“Aha! A hair follicle!”) I will tell you almost at the outset what happened, what this kid did, and you will read on anyway, to find out why he did it.

With this book I am moving away from the traditional plot-driven sort of mystery-suspense and toward a more psychological, interior sort of story. My first two novels are dissimilar in a lot of ways, but they are alike in one critical sense: both are intricate, tightly plotted mysteries. They are suspenseful in the way traditional mysteries are, which is to say, it matters “who dun it.” At least, it matters what exactly was done.

In my new book, which has no title yet, the suspense is not so much about who did what — that much is clear in the first few pages — but why he did it and how the crime affects everyone involved.

This story is a mystery, then, in the way all great stories are mysteries. The greatest mystery of all is other people, and understanding other people — empathizing, imagining what it like to be someone else — is the essential power of novels. I’d go so far as to say that recreating the interior, conscious experience of another person is the thing that novels do better than any other dramatic form.

I happen to have two sons, and I love them to no end. But they are individuals, with their own minds and their own wills. I can’t hope to know what it is really like to be them, what they think and feel. Like any fathers and sons, we are mysteries to one another. I think that’s a universal feeling. As fathers or sons, or mothers or daughters, we’ve all asked at some time or other, “What was he thinking?” This story simply imagines that question in an extreme situation: What if someone close to you, someone you loved and thought you knew, did something truly horrifying and unfathomable?

“All That Is Mine” Book Club Kit

On sale now!

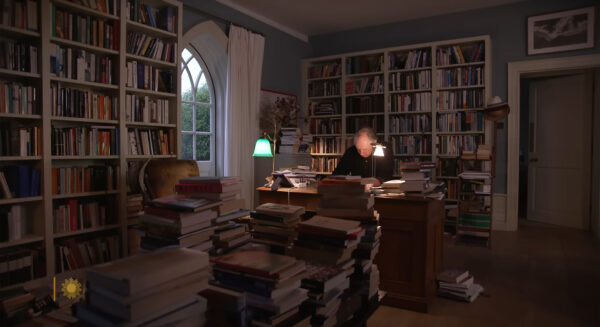

Today is publishing day — All That Is Mine I Carry With Me is officially on sale. We’ve been banging the drum for this book already. There are podcasts, essays, live appearances, and more on the way. And we’re doing as much social media as we can (including a peek at my office on Instagram). But there is no substitute for a book recommendation from a trusted friend. So if you’ve read the book and enjoyed it, please pass the word. Thank you to everyone who has helped in this effort, and I hope I’ll see you out on tour!

(Want to buy the book online? My publisher has gathered up links to all the most popular booksellers here.)