When we encounter a natural style, Pascal says, we are surprised and delighted, because we expected to find an author and instead found a man.

Archives for 2015

George Saunders on writing

Arthur Conan Doyle on the origin of Sherlock Holmes

The Virtue of Ignorance

A 1960 interview with Orson Welles about “Citizen Kane.”

Q: What I’d like to know is where did you get the confidence from to make the film with such —

A: Ignorance. Ignorance. Sheer ignorance. You know, there’s no confidence to equal it. It’s only when you know something about a profession, I think, that you’re timid, or careful or —

Q: How does this ignorance show itself?

A: I thought you could do anything with a camera that the eye could do or the imagination could do. And if you come up from the bottom in the film business, you’re taught all the things that the cameraman doesn’t want to attempt for fear he will be criticized for having failed. And in this case I had a cameraman who didn’t care if he was criticized if he failed, and I didn’t know that there were things you couldn’t do, so anything I could think up in my dreams, I attempted to photograph.

Q: You got away with enormous technical advances, didn’t you?

A: Simply by not knowing that they were impossible. Or theoretically impossible. And of course, again, I had a great advantage, not only in the real genius of my cameraman, but in the fact that he, like all great men, I think, who are masters of a craft, told me right at the outset that there was nothing about camerawork that I couldn’t learn in half a day, that any intelligent person couldn’t learn in half a day. And he was right.

Q: It’s true of an awful lot of things, isn’t it?

A: Of all things.

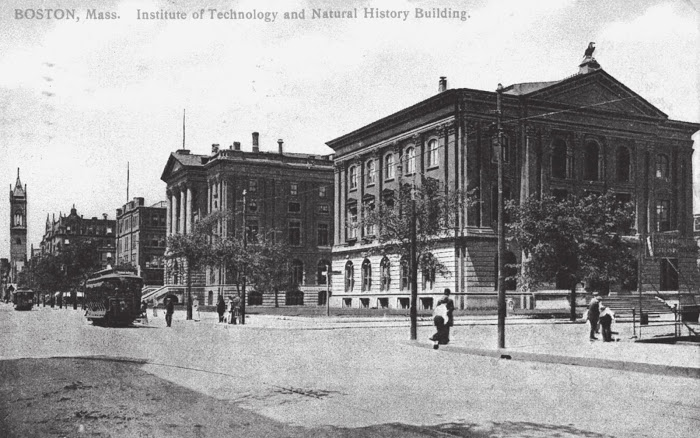

Postcard from the Back Bay

Looking up Boylston Street from the corner of Berkeley in the 19th century. At right is the New England Museum of Natural History, a predecessor of the Boston Museum of Science. (The building is now occupied by Restoration Hardware — sigh.) To its left is the Boston Institute of Technology, now MIT. The tower at the far left is Old South Church in Copley Square. (via) I work nearby and pass this spot every day.

Turning time into language

Adam Gopnik’s story on Trollope in the New Yorker touches on

his very Victorian work ethic: he wrote for money, and he wrote to schedule, putting pen to paper from half past five to half past eight every morning and paying a servant an extra fee to roust him up with a cup of coffee. He made a record of exactly how much each of his novels had earned, and efficiency and economy, taken together, got him a reputation as a philistine drudge.

Trollope was, in truth, merely being practical about the problems of writing: three hours a day is all that’s needed to write successfully. Writing is turning time into language, and all good writers have an elaborate, fetishistic relationship to their working hours. Writers talking about time are like painters talking about unprimed canvas and pigments.

Not sure I agree with Gopnik’s three-hour rule. Three hours a day may have been enough for Anthony Trollope to write successfully, but you, alas, are not Anthony Trollope.

It is interesting to think of writing as “turning time into language.” Of course, Gopnik is not saying that’s all writing is. He is making a simpler point about Trollope’s practicality and discipline. (Otherwise the phrase is meaningless: all art forms can be reduced to “turning time into” something — sculpture, music, painting, etc.). Still, it is a useful formulation for writers to keep in mind. Looking back at these monstrously productive Victorians, it is easy for a writer to get psyched out. Better to use Trollope as a daily reminder to turn your time into text, and be done with him.

Pixar’s story rules

A list of storytelling tips picked up at Pixar by Emma Coats, a former “story artist” there (via). Interesting.

- You admire a character for trying more than for their successes.

- You gotta keep in mind what’s interesting to you as an audience, not what’s fun to do as a writer. They can be v. different.

- Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

- Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

- Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff but it sets you free.

- What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

- Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.

- Finish your story, let go even if it’s not perfect. In an ideal world you have both, but move on. Do better next time.

- When you’re stuck, make a list of what wouldn’t happen next. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up.

- Pull apart the stories you like. What you like in them is a part of you; you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it.

- Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

- Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th — get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

- Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.

- Why must you tell this story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

- If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

- What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

- No work is ever wasted. If it’s not working, let go and move on — it’ll come back around to be useful later.

- You have to know yourself: the difference between doing your best & fussing. Story is testing, not refining.

- Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.

- Exercise: take the building blocks of a movie you dislike. How d’you rearrange them into what you do like?

- You gotta identify with your situation/characters, can’t just write “cool.” What would make you act that way?

- What’s the essence of your story? Most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build out from there.