Ernest Hemingway’s 1923 passport (detail). Hemingway is 24 years old. (Source: JFK Library, via.)

Archives for 2011

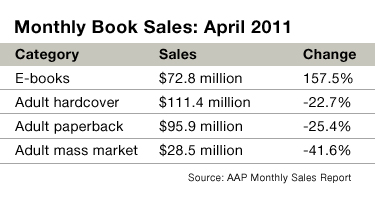

The Death of Print

See if you can discern the subtle pattern in these numbers. (Via.)

Leonardo, procrastinator

I was heartened (relieved, really) to find this wonderful essay describing Leonardo da Vinci as “a hopeless procrastinator.”

Leonardo rarely completed any of the great projects that he sketched in his notebooks. His groundbreaking research in human anatomy resulted in no publications — at least not in his lifetime. Not only did Leonardo fail to realize his potential as an engineer and a scientist, but he also spent his career hounded by creditors to whom he owed paintings and sculptures for which he had accepted payment but — for some reason — could not deliver, even when his deadline was extended by years. His surviving paintings amount to no more than 20, and five or six, including the “Mona Lisa,” were still in his possession when he died. Apparently, he was still tinkering with them.

Nowadays, Leonardo might have been hired by a top research university, but it seems likely that he would have been denied tenure. He had lots of notes but relatively little to put in his portfolio.

What makes the essay so interesting is the suggestion that Leonardo’s epic procrastination, far from being a character flaw or an impediment, was the very key to his creativity. So many of the things for which we celebrate Leonardo are the product of his procrastination, especially the notebooks which overflow with ideas and visions, daydreams about helicopters and double-hulled ships and so on. Leonardo’s notebooks are the primary reason we think of him as a genius, the archetypal polymath Renaissance man, rather than “just” a brilliant artist. And he was paid for none of that creative work. It is what he did when he ought to have been doing something else.

Would he have achieved more if his focus had been narrower and more rigorously professional? Perhaps he might have completed more statues and altarpieces. He might have made more money. His contemporaries, such as Michelangelo, would have had fewer grounds for mocking him as an impractical eccentric. But we might not remember him now any more than we normally recall the more punctual work of dozens of other Florentine artists of his generation.

I don’t want to get carried away. The lesson of Leonardo’s life is not to abandon yourself to procrastination. Procrastination has to be controlled. There is work to do, bills to pay. I get that.

At the same time, it is useful — for artists, especially — to think of procrastination not as a vice or a personal weakness, but as a signal, an alarm bell. It is the clearest possible indication that your current project is not inspiring to you. After all, you don’t put off something you enjoy doing. Your mind does not wander if it is engaged in something interesting.

The usual advice to procrastinators who yearn to be “cured” is to exert ever more discipline and hard work. Manage the problem. Put systems in place to help you complete a project that bores you to tears. Those are useful strategies, sometimes. Boring work simply has to get done, sometimes. But maybe, sometimes at least, we are looking in the wrong place. Maybe the problem is not the worker, but the work. Remember, it is the writer’s job never to be boring, and if a project is boring to the writer himself…

Every writer knows the self-lacerating guilt that accompanies unproductive days. Lately, I have been grinding away on a stalled, lifeless book. I have spent weeks on technical problems: trying to piece together the story or engineer characters to fill various plot functions. Or simply struggling to find new ideas worth writing about. It is an inefficient, unproductive, maddening part of the process. And of course I have bashed myself endlessly for procrastinating, for all the lost hours.

But maybe I ought to be asking not what’s wrong with me, but what’s wrong with this novel? Why doesn’t it inspire me? Or, more usefully, how can I turn it into the sort of novel that will inspire me? Every writer, every artist, of even moderate ambition wants to work with passion, on projects that fill him with a sense of mission. If the project before you does not do that, then change it till it does.

For a lot of writers, I admit, that is terrible advice. Certainly it contradicts the received wisdom. When wise old writers pontificate about How To Write, one chestnut they always toss off is “Don’t wait for inspiration.” And it is true that there are plenty of writers out there who work whether they are inspired or not. They churn out a book a year, steady, workmanlike, professional, unsurprising, consistent, well-crafted books. I admire them. I envy them, honestly. You should emulate them if you can.

But I don’t want to work that way and I don’t want to write books like that. I want every book to be the best fucking thing I’ve ever done. I want every book to be electric — a mission, not just a paycheck. I want to work at the absolute outer limit of my talent, always. That sounds naive and grandiose, I know, but there it is.

We writers always complain about modern readers. “They have lost their ability to focus deeply. The web has ruined them. They read like rabbits, skittish, hopping here and there. They don’t have the necessary attention span for novels. Novels are dying because of them.” We ought to remember that when we procrastinate, when we feel uninspired, our own mood — distracted, disengaged, dull, sniffing about for something interesting — is very much like the resting state of our audience. It is our job to make novels so intensely interesting that rabbity modern readers will feel they have to read them. They will close their laptops, turn off their ginormous high-def TVs, and pick up a book instead. The surest way to do that is to choose projects that are so intensely interesting to ourselves that we feel the same sort of compulsion to close our web browsers and get to work.

Procrastination is not always bad. It may be a signal. If you consistently feel you’d rather be doing something else, then your project is obviously lacking something. Don’t ignore that signal. Use it.

(Now go read that essay on Leonardo.)

Southie reacts to the capture of Whitey Bulger

NHL ’67

Amazing footage of the 1967 NHL season (though you may want to turn the sound down).

Making books is fun!

“This man is an author. He writes stories. He has just finished writing a story. He thinks many people will like to read it. So he must have the story made into a book. Let’s see how the book is made.”

Mencken on great artists and virtuous men

The great artists of the world are never Puritans, and seldom even ordinarily respectable. No virtuous man — that is, virtuous in the Y.M.C.A. sense — has ever painted a picture worth looking at, or written a symphony worth hearing, or a book worth reading.

H.L. Mencken