Linda Stone on attention in the age of web overload. This 2006 talk is remarkably prescient. The addled, distracted feeling she described five years ago as “continuous partial attention” feels like a permanent condition now.

Archives for 2011

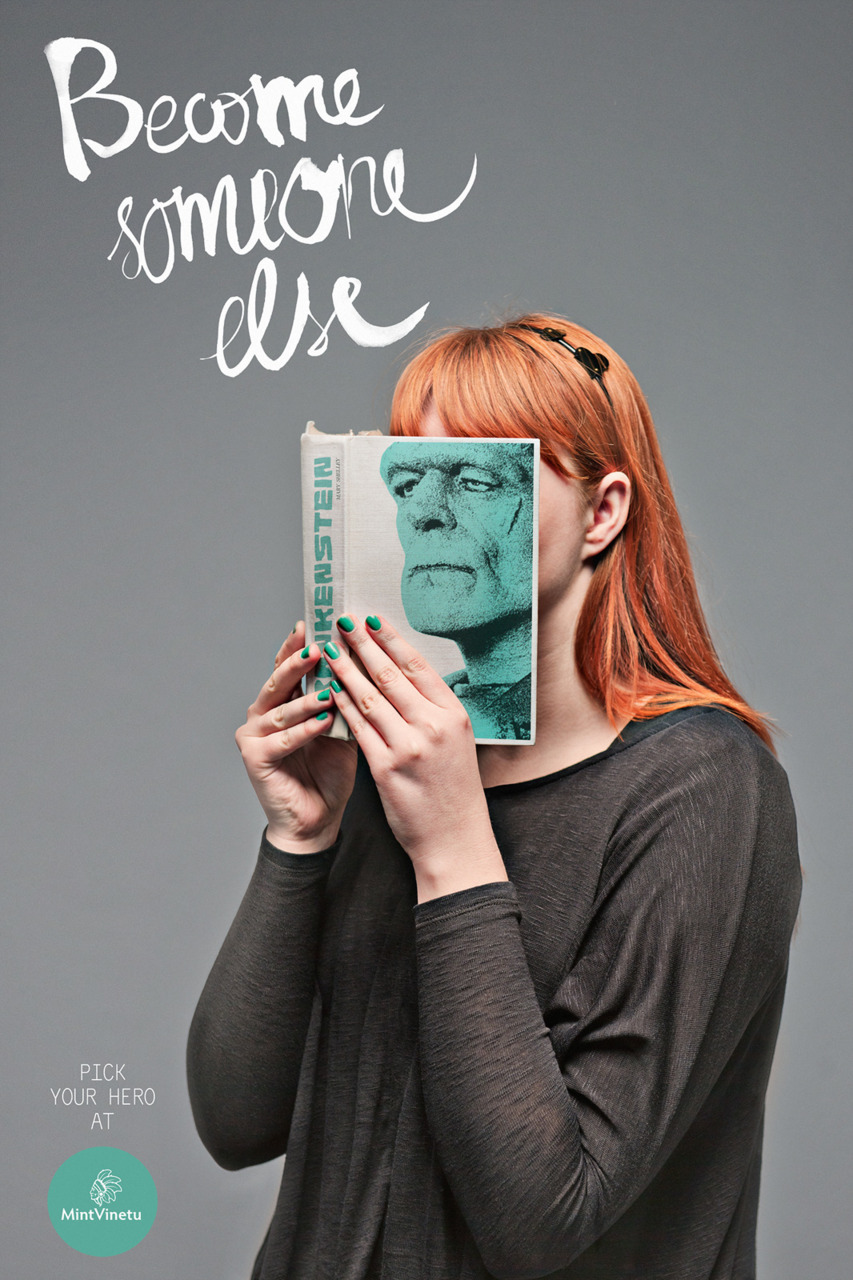

You are what you read

Wonderful ad for a bookstore in Lithuania called Mint Vinetu. (Via Quipsologies.)

Mark Twain on film

Mark Twain at his Connecticut home in 1909.

New York, 1902

The Flatiron Building under construction, ca. 1902. (Via Library of Congress.)

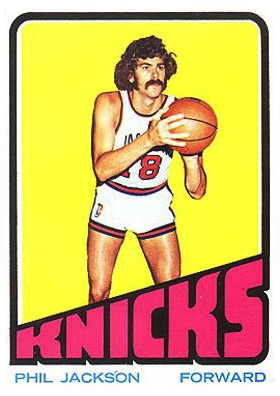

Phil Jackson, 1972

Robert Longo: Shark

Robert Longo

Untitled (Shark 4)

2008

Charcoal on mounted paper

88 x 70 inches/223.5 x 177.8 cm

Golden Gate Bridge under construction

Robert Campbell on Boston’s Human Scale

Boston’s Old State House … was a perfectly normal-sized building when it was erected, in 1713. But today, surrounded by skyscrapers, it is completely transformed. It possesses a new charm, a charm its architect could never have envisioned: the charm of a tiny jewel or an exquisite ivory carving. Or a child. Among the tall, blank, dark buildings that surround it, the Old State House, with its slightly loony ornaments — a lion and a unicorn — resembles a child in Halloween costume being escorted around the neighborhood by the FBI.

What is true of the Old State House as a building is equally true of Boston as a city. Once Boston, too, was a city of average scale. That’s not the case anymore, not when you compare Boston with the typical American megalopolis, with its vast, bleak stretches of freeway and strip malls. By contrast, we’ve become Tiny Town.

Quite literally so. Boston comprises just 46 square miles of total area. Phoenix is 324, Los Angeles, 465, Honolulu, 596. The new Denver airport is bigger than all of Boston. You could put Louisburg Square in the center strip of many American downtown arteries and forget where you’d left it; it would resemble a minor traffic island. Or take our so-called skyscrapers. No fewer than 12 other US cities boast towers higher than the Hancock, our tallest. Chicago and New York between them have 22. There are several reasons why our buildings are smaller, the most important of which is that most of Boston’s subsoil is muck, not bedrock like Manhattan’s. By the time technology had solved the foundation problem, Bostonians were used to their smaller scale.…

[O]ur perception of scale has a lot to do with our life cycle as human beings. We were all small once, and we all got bigger. In that sense, we are all Alice in Wonderland: In our imaginations and our dreams, we’re always growing and shrinking. When we were little, a table was huge; we couldn’t see over the top of it. The memory of being so overwhelmed is one reason we enjoy miniatures, like doll houses and architectural models.… Why else do we flock to the famous “Main Streets” at Disneyland and Walt Disney World? All the buildings along these streets are built at three-quarters the size they would be in real life. The Disney people always get us right: In a world grown too big, we gravitate to a street that is just a little bit too small. It makes us feel more important, and it makes the world feel more manageable.

…When the “wrong” size is too big, it may command awe. When it is too small, it will often inspire love.

Boston, more than any other major American city, is a place that is filled with opportunities for that kind of affection.

Robert Campbell, “Small Wonders”