The last couple of weeks I’ve been cleaning up a few final details for my last novel and trying — futilely — to get the next one started. How, exactly, do you start writing a novel? Honestly, I have no idea. I’ve been spending my days writing and unwriting the same few sentences, kneading the same few barren ideas in the hope they will yield something new — a character, a scene. So far, nothing.

Of course, the initial stages of a new project are always hard. There is nothing to work with, just a few very vague concepts and reams and reams of blank pages. Big deal, right? I’ve been here before. I know how the process works. I know this period is going to suck. I expect it to suck. The trouble is, well, it has sucked.

It is an intractable fact of the writing life: a writer who stops writing for any reason is vulnerable to all sorts of infection. Laziness. Time-wasting. Loss of confidence. Now a new peril: impostor syndrome, as the rave reviews for my just-completed novel increasingly diverge from the endless fail-loop of my workdays, and the disconnect between hype and reality becomes harder and harder to ignore.

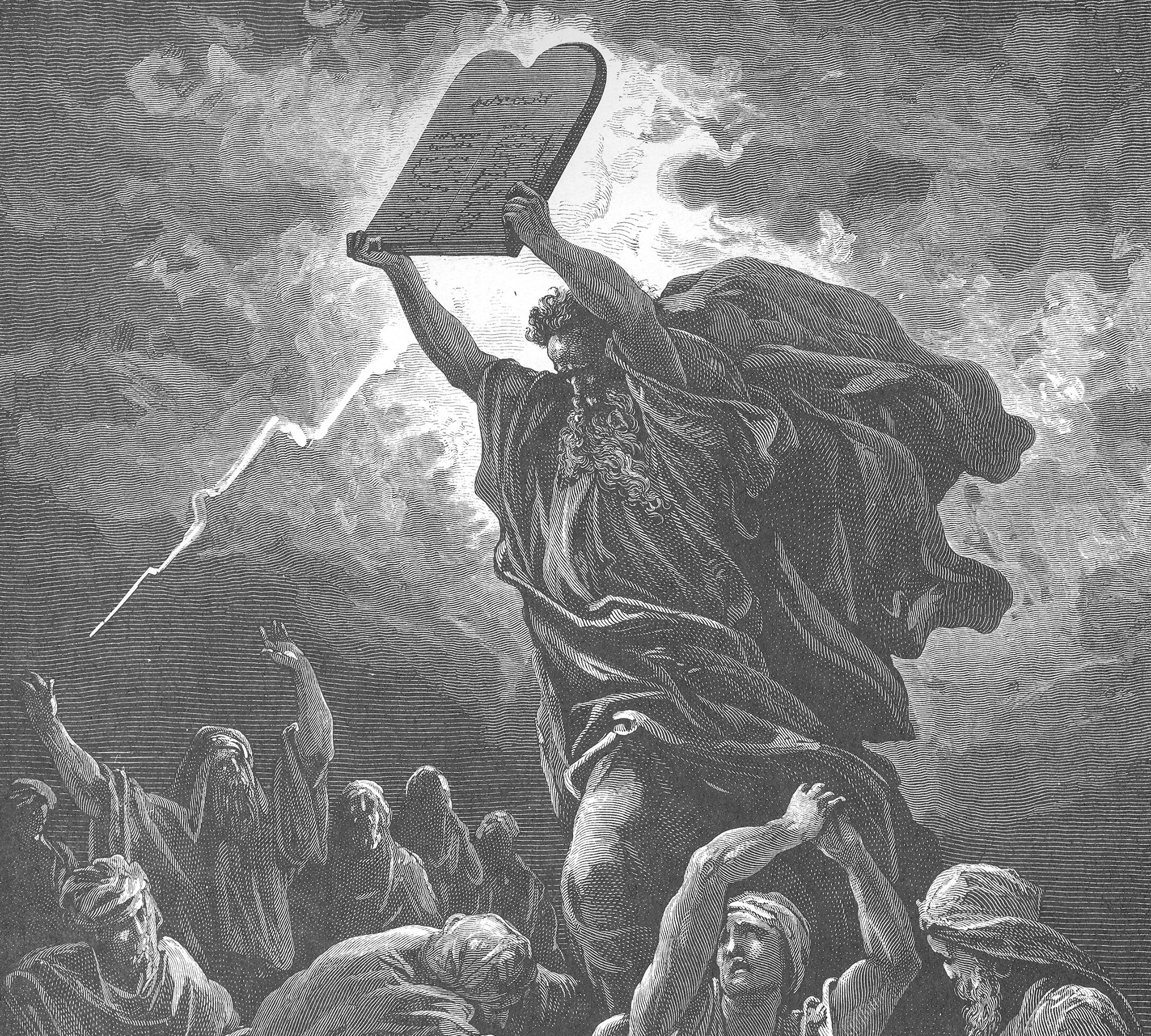

Enough is enough. Herewith, a reminder to myself of some basic rules. They aren’t really commandments; in fact, they may not work for other writers at all. And there aren’t even ten. But they’re important enough to me to recite them here, again. (If you’ve been reading this blog awhile, you’ve probably run across these ideas in bits and pieces.) These are the things I tend to forget when I fall into an unproductive rut in the beginning stages of a novel, as I have now.

1. Churn

In his book Weird Ideas That Work: How to Build a Creative Company (excerpted here), Stanford engineering professor Robert Sutton wrote:

Researcher Dean Keith Simonton provides strong evidence from multiple studies that creativity results from action. Renowned geniuses like Picasso, da Vinci, and physicist Richard Feynman didn’t succeed at a higher rate than their peers. They simply produced more, which meant that they had far more successes and failures than their unheralded colleagues. In every occupation Simonton studied, from composers, artists, and poets to inventors and scientists, the story is the same: Creativity is a function of the quantity of work produced.

That last phrase — creativity is a function of the quantity of work produced — distills so much of my own experience. I have always thought too long and written too slowly, under the misapprehension that if I planned carefully enough, I could avoid failure. It doesn’t work that way. Any creative project involves risk-taking. Some percentage of these risks will fail. Nobody bats a thousand. The logical response is not to take fewer risks, to fall back on formula and imitation; timidity and calculation will never produce a great book (or great art of any kind). No, the logical approach is to produce a lot of work — a lot of pages during the writing process, and ultimately a lot of novels. You will produce more good books that way. More bad books, too, but no one will remember or care about them. Posterity will judge you only by your best books.

So move quickly from concept to execution, from dreaming to writing. Get the ideas in your head out onto paper, force those ideas into an outline somehow, then start writing a draft as quickly as possible. Conceptualize less, iterate more. Think less, act more. Churn out pages, even lousy ones.

More often than not, you will fail. It’s part of the process. Remember Beckett: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” That’s how writing works.

2. “Keep the seed in the ground”

Sutton again:

In fact, creative work must be sheltered from the cold light of day, especially when ideas are incomplete and untested. William Coyne, former vice president of R&D at 3M, remarked in a speech at Motorola University, “After you plant a seed in the ground, you don’t dig it up every week to see how it is doing.” … Psychological research shows that people are especially hesitant to try new things in front of “evaluative others” like critics and bosses.

Don’t share your work too soon. Resist the urge to reach out for reassurance or creative input. A story needs time to come together. In its earliest stages, it is a fragile thing, much too delicate to be exposed to criticism. I am convinced I have lost whole books because I shared early manuscripts with “evaluative others” before the stories had coalesced into something real. (This is one reason I have never participated in writing groups or writing classes. I prefer to nurture my babies in private.)

3. Believe

A few months ago I linked to this bit of advice from Merlin Mann: “First, care. Care intensely. … Know in your heart that what you’re making or doing matters.” Mann meant this advice as a cure for procrastination, but to me it has special relevance to novelists.

“Know in your heart that what you’re making matters.” That sort of faith has always been hard for writers to maintain, even in the best of times. Bookstores and libraries have always been dauntingly crowded with thousands of books. Who needs your book? But it is especially hard for novelists to keep faith now, when every news story, every tweet, every blog, every wised-up voice tells you to give up. Publishing is dead. Books are dead. The novel is an obsolete art form. Newer media are more immersive, more compelling. Even Philip Roth, our greatest living novelist, constantly and confidently predicts the end of the novel. “I think [novel reading is] going to be cultic,” he has said. “I think that always people will be reading them, but it will be a small group of people, maybe more people than now read Latin poetry, but somewhere in that range.” Latin poetry! Why bother?

Here’s what I think: I believe in the unique power of the novel. I believe long-form storytelling will survive the transition to digital and even thrive. Yes, printed books are going away; but reading is not going away, stories are not going away. And even if the doomsayers are right and the whole damn thing is going down, I say, Fuck it. This is what I am. This is what I do. I am committed to this art form and to my own work.

If you allow those doubting voices to creep into your head — if you believe that there will soon be no market to sell your book and no audience to read it — then you’re through even before you start.

4. Work!

Novel-writing requires conflicting traits. Roughly speaking they fall into two categories, creativity and discipline. You have to be inventive enough to imagine something entirely new, something no one has ever seen; but disciplined enough to labor for years carpentering your idea into existence. You have to be sensitive enough to perceive and describe the finest subtleties of human experience, but thick-skinned enough to block out unhelpful noise — and utterly stone-deaf to criticism. You have to be a wild, iconoclastic visionary in dreaming up your story, then dull and disciplined as a banker in executing it. Without both sides of your personality, you will fail.

My experience the last few weeks has been that when the creative side fails, it takes down the discipline side with it. It is hard to maintain good work habits when all you have to do at work is stare at a blank computer screen. Why rush off to the office when there is nothing to do once you get there? Soon enough things go from bad to worse. You procrastinate, just a little. You sleep a little late, then a little later and a little later. You work too little and without the necessary intensity. Pace Woody Allen, novel-writing is not a job where 80% of success is just showing up. You’d damn well better show up ready to work with ultimate focus every single day.

There’s no secret to snapping out of bad habits like these. You just have to show ever more discipline. Do the things you know you should be doing. Don’t procrastinate; get right to work in the morning. Count words or count pages — but count something. (The watched variable is the one that moves.) Unplug from the internet. Take care of yourself: sleep, exercise, eat well, socialize. Maintaining that sort of discipline is especially hard now, at the beginning of a project. Too bad. Do it anyway.

All of this sounds like a counsel of perfection, so I’ll say again that I break all these rules all the time — and you will, too. Welcome to the writing life. There’s nothing for it but to keep trying. “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

5. Enjoy the journey

I ran across an interview with Junot Díaz recently in which he said,

The crazy thing about the arts is it’s not like other stuff where you can build up muscle to help you with the next project. A friend of mine, he’s a surgeon, he’s like a combat surgeon in Iraq, and we grew up together and immigrated together, and he tells me every surgery makes you even more awesome for the next surgery. I’ve never felt that anything I’ve written has made me more awesome.

That has been my experience, too. Every time I start a new novel, I come to it an absolute beginner, no matter how many novels I’ve written before. From earlier projects, I’ve certainly gained perspective. I don’t worry anymore about whether I am capable of completing a project of this scale. But how to write this particular project? How to find this story, these characters, this new voice — all things that no one, including me, has ever seen? There is just no way to prepare for that.

The key is to enjoy being a beginner. Steve Jobs put it nicely in his 2005 Stanford commencement speech when he talked about being fired from Apple in 1984: “The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.” The lightness of being a beginner — that’s a nice phrase.

Think about it: being a beginner frees you. It frees you from constricting habits and expectations. It frees you to try new things. It frees you to invent from scratch rather than repeat the same book over and over, which is to say, it frees you to reinvent yourself. To rediscover the vaulting, naive ambition you had at the very beginning, when setting out to write a novel seemed like a heroically ballsy thing to do.

Writing a novel is a journey for the novelist, and the book itself is only the artifact of that journey. The reader will make her own journey when she reads the novel, of course, and obviously her experience will be different from yours. She will experience the novel from the inside, in the seamless world you have made for her, led along page by page at the pace you have set for her. The novelist’s journey is infinitely harder, since there is never a next page. But there is no way to make the journey any easier, not by overplanning, not by delaying the jump-off date. In the year or two or three that it takes to write a novel, troubles will come. Count on it. The danger that this time you will not be able to solve them — the awareness that the journey is dangerous, the risk, the uncertainty, the adventure, the challenge — is precisely the attraction.

Good stuff. Talking of ‘beginners’, this weekend I found my old writing books from primary school. Alongside an awful lot of scribbled planes and cars and explosions are stories my five year old brain imagined and then toiled to get the pencil in my little fingers to scratch out. I don’t think I could ever come up with them again – the tales darting nimbley from dragons to being poorly to playing with friends to Mr Dreamy, an apparent imaginary friend. They all seem so spontaneous and free. No fear of the blank reams then.

I’d like to get back to that sort of creative freedom, and soon. Hang onto those old notebooks, Philip — you never know.