Lydia Davis’s new translation of Madame Bovary is terrific. With my klutzy high-school French, I am not qualified to judge the accuracy of the translation (Julian Barnes does that here). All I can say is I enjoyed the book on this rereading much more than I have in the past, when reading it felt like swimming upstream. It may be that I was simply too young for the book on my first, joyless read. This time I loved it.

Davis’s version of the novel feels quite contemporary in style. Of course, part of the credit for that goes to Davis, herself a graceful fiction writer. But the larger point is that, in September 1851 when he sat down to begin writing Madame Bovary, in his second-floor study using a quill pen, Flaubert envisioned something radically new — what we recognize now as the modern realist novel. Like the old joke about the fish who cannot see the water all around him (“What water?”), it is hard for contemporary readers to see what Flaubert is doing in Madame Bovary that is so innovative. As Davis explains in her foreword to the new translation, the novel “is now viewed as the first masterpiece of realist fiction. Yet its radical nature is paradoxically difficult for us to see; its approach is familiar to us for the very reason that Madame Bovary permanently changed the way novels were written thereafter.” Realism — the mimetic, naturalistic depiction of human experience — is the water that all of us, writers and readers, now swim in.

It is too much to say that Flaubert invented realism with Madame Bovary, but he has a pretty good claim as the author who envisioned it most clearly and actually captured it. His intent in writing Bovary, in the words of biographer Frederick Brown, was to “[make] the world materially present through language — [to abolish] the space between words and what they represent.” He wanted to capture life as it is actually experienced, without commentary or embellishment. “No lyricism, no reflections,” Flaubert declared in a letter, “the personality of the author absent.”

It was precisely the author’s absence in Madame Bovary — the lack of a wise, moralizing voice forever commenting on the action — that triggered an obscenity charge against the novel. The trouble was not that the book was lewd. On the contrary, it was about as prim as a novel about serial adultery can be. The trouble was that it never explicitly condemned Emma for her adultery. It simply described. The government prosecutor raged that “there is not a single character who can make [Emma] bow her head, not an idea or line in virtue of which adultery is scourged.” After a one-day trial, the book was exonerated, though the court’s decision noted that the author had “lost sight on occasion of the rules that every self-respecting writer should not violate, and … [forgot] that literature, like art, will accomplish the good it is called upon to do only if it be chaste and pure in substance as well as in form.”

To modern readers, the complaint seems a little nutty. Stop the story to “scourge” Emma? To sermonize on the wickedness of fornication? Who on earth would want to read that?

That is precisely why we are still reading Madame Bovary after 150 years, when most of its contemporaries are long forgotten. The story feels accessible and real, especially in Davis’s translation. Emma comes across as a real person. She is bored and horny and weak, and so are the men around her — and so, for that matter, are you and I. What makes Emma so sexy even today is that we see her precisely as the men around her did. Flaubert insists on Emma’s physical reality, a beautiful woman in stylish clothes, in a dreary provincial town. Her mere physical presence is a provocation.

Consider two brief passages. Here is how the lonely young law clerk Léon sees Emma in their early encounters, at nightly soirees hosted by the town’s windbag pharmacist, Homais:

First they would have a few rounds of trente et un; then Monsieur Homais would play écarte with Emma; Léon, behind her, would give advice. Standing with his hands on the back of her chair, he would gaze at the teeth of her comb biting into her chignon. With each movement she made laying down her cards, her dress would lift on the right side. From her pinned-up hair, a brownish shadow descended her back and, paling by degrees, gradually lost itself in the darker shadows. Her skirt lay draped over the chair on both sides, ballooning out in ample folds, and spread down to the floor. When sometimes Léon felt the sole of his boot resting on it, he would draw back, as though he had stepped on someone.

A similar passage occurs just a few pages later, when Emma meets the cad Rodolphe. In this scene, Emma assists her doctor-husband, who is treating a sick patient. Again we are reminded of Emma’s body as it shifts in her dress.

Madame Bovary took the basin. With the movement she made, bending down to put it under the table, her dress (it was a summer dress with four flounces, yellow, long in the waist, wide in the skirt) flared out around her over the stone floor of the room; — and as Emma, stooping, swayed a little, putting out her arms, the material swelled and subsided here and there, following the contours of her body.

What Flaubert is doing here is leering at a beautiful woman. Rather, he is forcing us to. He is forcing us to see Emma as her two lovers do when they first encounter her, eyeing her up and down, standing over her shoulder and looking down her dress, stealing glimpses of her body. Flaubert is insisting we be conscious of Emma as a physical, sensual, exciting woman — insisting we feel the power of her presence. In short, he wants us to see Emma as if she were real, as men and women actually see each other every day, now as then, on trains and sidewalks, in bars and coffee shops, eyeing each other with secret desire and longing.

When Emma dies, Flaubert writes, “She had ceased to exist.” It is a weird phrase. But it is probably as good a definition of realism as any: for Flaubert, Emma actually existed for as long as he wrote her, and will as long as we continue to read her.

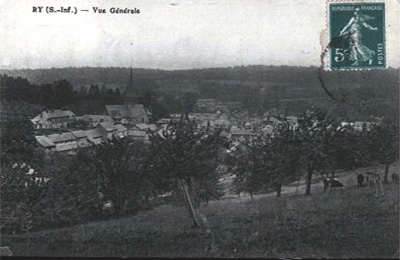

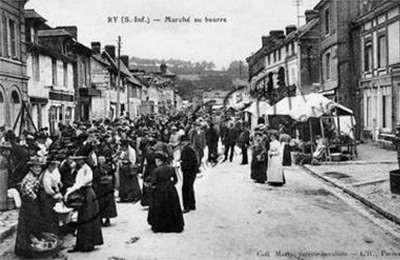

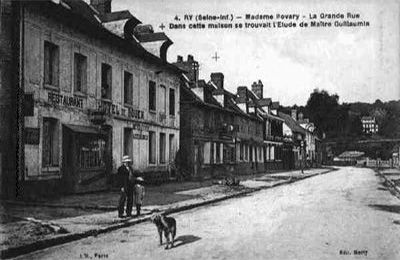

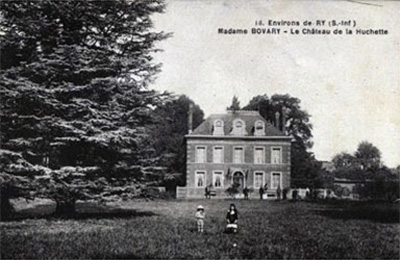

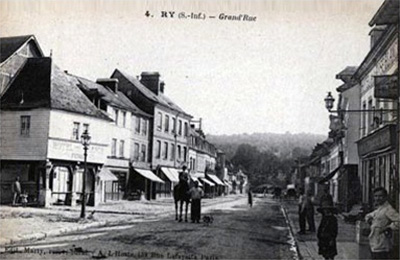

Image: Postcards of Ry, the village near Rouen that is widely considered the model for the fictional Yonville, where Emma Bovary was so miserable. Click to view hi-res. More antique postcards of Ry are here.