In a famous chapter of Moby Dick, Melville explains the law governing ownership of whales at sea.

It frequently happens that when several ships are cruising in company, a whale may be struck by one vessel, then escape, and be finally killed and captured by another vessel; and herein are indirectly comprised many minor contingencies, all partaking of this one grand feature. For example,— after a weary and perilous chase and capture of a whale, the body may get loose from the ship by reason of a violent storm; and drifting far away to leeward, be retaken by a second whaler, who, in a calm, snugly tows it alongside, without risk of life or line. Thus the most vexatious and violent disputes would often arise between the fishermen, were there not some written or unwritten, universal, undisputed law applicable to all cases.…

I. A Fast-Fish belongs to the party fast to it.

II. A Loose-Fish is fair game for anybody who can soonest catch it.

…What is a Fast-Fish? Alive or dead a fish is technically fast, when it is connected with an occupied ship or boat, by any medium at all controllable by the occupant or occupants,— a mast, an oar, a nine-inch cable, a telegraph wire, or a strand of cobweb, it is all the same. Likewise a fish is technically fast when it bears a waif [ed. note: a pole stuck into the floating body of a dead whale as a marker], or any other recognized symbol of possession; so long as the party wailing it plainly evince their ability at any time to take it alongside, as well as their intention so to do.

In other words, the moment a whaler sinks a harpoon into a whale, the whale becomes his legal property — but only as long as he manages to remain attached to it. If the whale escapes, alive or dead, it becomes a wild animal again, a loose fish, and the next boat to throw a harpoon into it becomes its legal owner. (Generally, the same principle applies to hunting wild animals on land, too.)

The idea of fast fish and loose fish, it turns out, is a useful way of thinking about lots of things.

What are the sinews and souls of Russian serfs and Republican [i.e. American] slaves but Fast-Fish, whereof possession is the whole of the law? What to the rapacious landlord is the widow’s last mite but a Fast-Fish?… What was America in 1492 but a Loose-Fish, in which Columbus struck the Spanish standard by way of wailing it for his royal master and mistress?… What is the great globe itself but a Loose-Fish? And what are you, reader, but a Loose-Fish and a Fast-Fish, too?

I have been thinking about all this lately because I have the happy, hopeful feeling that in choosing Boston’s old Combat Zone as the subject of my next book, I have stuck my harpoon into a loose fish — one that I am surprised to find is still there for the taking. I had this same impression when I first picked the Boston Strangler as the subject of my second book: how was it possible that this signature, iconic Boston crime story had never been treated in a novel before? With all those “Boston crime novelists” out there typing away, I figured there must be no Boston crime stories left to tell. There are. But only a few.

Of course writers do not — and should not — respect the law of fast fish and loose fish. Every story is a loose fish, strictly speaking. Nobody can own it, no matter how well or how famously or how often the story has been told before. The story of the Boston Strangler is still a loose fish, even with my harpoon — even with a thousand harpoons — dangling from its side. That is how art and ideas work. By borrowing, remixing, reimagining. “Chinatown” is a riff on Dashiell Hammett, “L.A. Confidential” is a riff on “Chinatown,” on and on.

At the same time, every storyteller is constantly on the lookout for a truly loose fish — a fresh story that has never been told, never claimed by someone else. So many story ideas feel like fast fish to me, positively bristling with harpoons. A story about Boston’s underworld? Feels like George V. Higgins. A story about Boston’s neighborhoods? Feels like Lehane. So it goes. Especially in a genre as old as crime and detective stories, there just aren’t many untold stories left. As I’ve said before, it’s all been done.

So it is exciting to find a story that feels utterly new. Now, having speared it, the job is fight that whale and not let it get away, or it will become a loose fish once again.

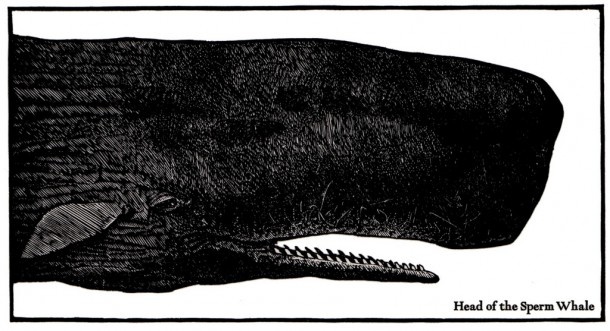

Illustration: Barry Moser, “Head of the Sperm Whale,” from a collection of a hundred woodcuts Moser created for a 1979 fine-art edition of Moby-Dick. (via)