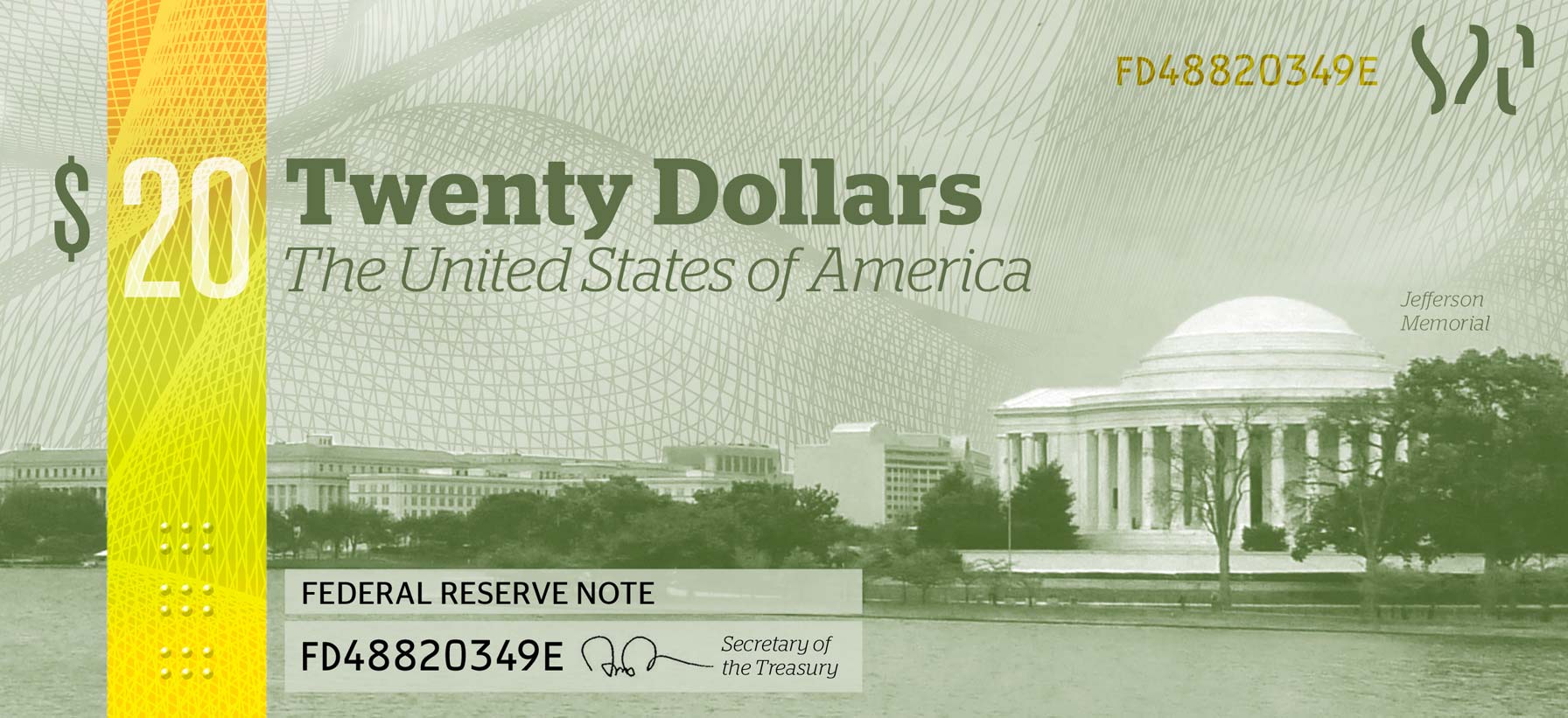

Designer Michael Tyznik’s concept for a redesign of American currency (rejected, of course).

Official website of the author

Designer Michael Tyznik’s concept for a redesign of American currency (rejected, of course).

“Nothing is so fatiguing as the eternal hanging on of an uncompleted task.”

— William James

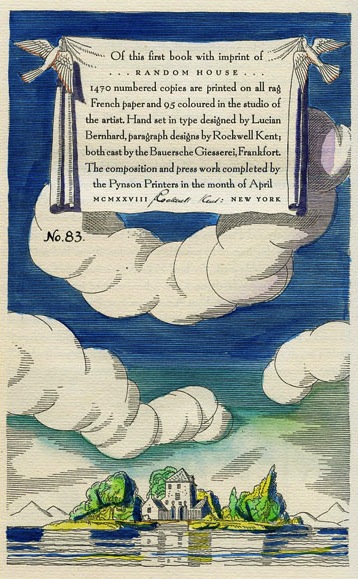

What is that little house in Random House’s logo? The New York Public Library explains (via):

In 1928, Random House commissioned the great American artist Rockwell Kent (1882–1971) to illustrate Voltaire’s Candide as the first book under its imprint. The volume’s colophon page contains the image of a house — intended to be where Candide and his companions lived and where they cultivated the final garden of the tale — which became the company’s logo, still in use today. Kent’s Candide is one of the landmarks of the American illustrated book, with specially made paper from France, a new typeface from Germany, and multiple illustrations, all exquisitely integrated. Random House issued a limited edition of 1,470 copies and another 95, these hand-colored in the artist’s studio.

Now, about that Bantam rooster…

Image: Kent’s colophon page for the 1928 Candide, number 83 of a limited edition of 95 copies hand-colored in Kent’s studio. Approximate value of the rare hand-colored books: $25,000. Image source: Felt & Wire.

Read more on Candide, including the Rockwell Kent edition, at the NYPL’s site for the recently closed exhibit on the book. About Voltaire himself, look here.

Sven Birkerts on reading in a digital age in which “the novel is the vital antidote to the mentality that the Internet promotes”:

We always hear arguments about how the original time-passing function of the triple-decker novel has been rendered obsolete by competing media. What we hear less is the idea that the novel serves and embodies a certain interior pace, and that this has been shouted down (but not eliminated) by the transformations of modern life.

The essay takes a while to find its feet, in part because Birkerts seems to be thinking through the problem as he writes, but also because the subject is so damn complicated — how do we read novels now, and why bother?

Philip Roth at his home in rural Connecticut, 2004. (Via.) Photo by James Nachtwey. More about Roth’s work habits here.

“A novel, like a letter, should be loose, cover much ground, run swiftly, take risk of mortality and decay.”

— Saul Bellow, letter to Bernard Malamud (1953)

From “The Background Hum: Ian McEwan’s Art of Unease,” by Daniel Zalewski, The New Yorker, 2.23.09:

… McEwan keeps a plot book — an A4 spiral notebook filled with scenarios. “They’re just two or three sentences,” he said.…

McEwan said that he never rushes from notebook to novel. “You’ve got to feel that it’s not just some conceit,” he said. “It’s got to be inside you. I’m very cautious about starting anything without letting time go, and feeling it’s got to come out. I’m quite good at not writing. Some people are tied to five hundred words a day, six days a week. I’m a hesitater.”

When McEwan does begin writing, he tries to nudge himself into a state of ecstatic concentration. A passage in “Saturday” describing Perowne in the operating theatre could also serve as McEwan’s testament to his love of sculpting prose:

For the past two hours he’s been in a dream of absorption that has dissolved all sense of time, and all awareness of the other parts of his life. Even his awareness of his own existence has vanished. He’s been delivered into a pure present, free of the weight of the past or any anxieties about the future.… This state of mind brings a contentment he never finds with any passive form of entertainment. Books, cinema, even music can’t bring him to this.… This benevolent dissociation seems to require difficulty, prolonged demands on concentration and skills, pressure, problems to be solved, even danger. He feels calm, and spacious, fully qualified to exist. It’s a feeling of clarified emptiness, of deep, muted joy.

For McEwan, a single “dream of absorption” often yields just a few details worth fondling. Several hundred words is a good day.… He told me, “You spend the morning, and suddenly there are seven or eight words in a row. They’ve got that twist, a little trip, that delights you. And you hope they will delight someone else. And you could not have foreseen it, that little row. They often come when you’re fiddling around with something that’s already there. You see that by reversing a word order or taking something out, suddenly it tightens into what it was always meant to be.”

The only mood in which to start writing is self-disgust. Writing becomes an act of atonement for procrastination — and “self-waste.”

— Alain de Botton, master Twitterer