There is a new exhibition at the Boston Public Library of the street photographs of Jules Aarons. The exhibition is located in the Wiggin Gallery in the old McKim Building, just one flight up from the main reading room where where I have been writing every day. The gallery is secluded, and you won’t find much signage or advertising for the exhibit, even in the library itself. The guardians of the BPL apparently have decided to keep this one a secret. That is a shame but not exactly a surprise. Aarons’s work has been underappreciated for a long time now. He is one of the best photographers you’ve never heard of.

I wandered up to the Wiggin Gallery this morning before work, happy to postpone writing a difficult scene that I have been struggling to complete. In the gallery, two women were strolling past the pictures and chatting. They soon wandered off, and I had the entire exhibition to myself. The room was quiet, not the usual library sort of quiet — footsteps, sniffles, sneezes, whispers — but dead quiet. It was an odd place to see these pictures, which are so alive you half expect the people in them to turn to you and speak. (“Get back to work,” they might tell me.)

It is a mystery to me why Aarons’s photographs are not better known. I am not enough of a connoisseur to comment on the technical proficiency of the pictures, but to me they seem expertly composed and printed. Certainly they are very beautiful. Aarons’s street photography has been compared to the work of Lisette Model, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Helen Levitt, and Aaron Siskind, among others. Again, I am not qualified to comment on the comparisons. But I know what I see in these pictures and why I love them: they are alive, authentic, intimate, humane.

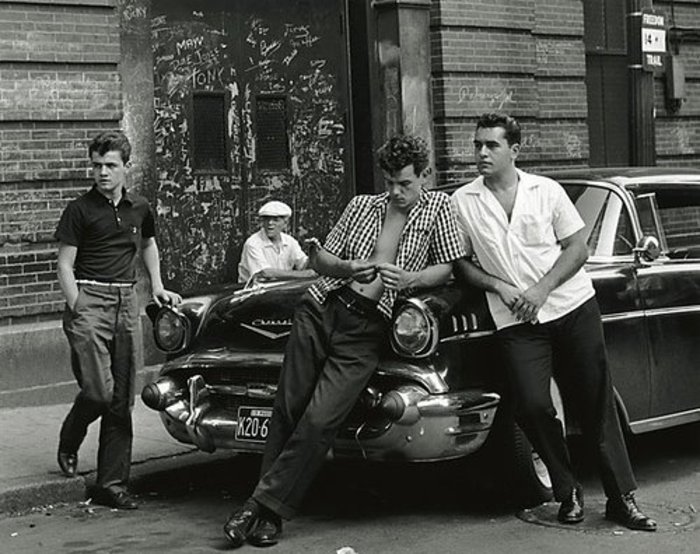

Most of the photos in the exhibition date from about 1947-1960, some later. They show ordinary working-class people, often in the West and North Ends of Boston, doing nothing more than chatting on street corners or flirting or lighting a cigarette. Fifty or sixty years later, of course, these people are all gone or transformed by age, but they are utterly alive and present in Aarons’s pictures. To come face to face with them is like traveling back in time. It makes the hair on your neck stand up.

I first discovered Aarons’s work when I was researching The Strangler. His images were always in my head when I closed my eyes and imagined the city during the Strangler period. I even considered approaching him to license one of his images for the book jacket, he so perfectly catches the period feel I was looking for.

Aarons, who died recently at age 87, was never a professional artist. In fact, he was a renowned physicist, an expert in an arcane study that has something to do with radio waves in the atmosphere. Photography was a sort of second career for him. One wonders how a scientific mind could create pictures so soulful.

I suspect that, upon moving to Boston in 1947, Aarons found in the crowded streets of the West and North Ends a subject that reminded him of the Bronx neighborhood where he grew up in the 1920s and ’30s. He was at home in city streets. He seems to have enjoyed the bustle of urban life. His pictures are full of kids playing on sidewalks and women gossiping on tenement stoops and young men leaning on parked cars. I may be biased, but to me he seems especially at home in the streets of this city. His pictures of other places — Aarons traveled and photographed widely — do not have the same vitality and dynamism as the early Boston pictures. His images of Paris and, later, Peru are more abstract, more composed, more consciously artistic. I do not mean that as a criticism. An artist has a right to evolve, to work in a different, cooler style. But I do love the early, raw Boston pictures on display at the BPL.

Aarons’s method was unobtrusive. He used a boxy twin-lens Rolleiflex held at the waist, which gave him an unexpected advantage.

The waist level position allowed me to point my body in one direction and the camera in another. It was important to me not to intrude on the scenes which ranged from card playing in the streets to adults talking to one another.

The effect is like spying on real people, unposed, unself-conscious, unaware of our gaze. It is like visiting a lost Boston — precisely the fantasy I indulged in The Strangler. To see that city here, reanimated in Aarons’s photographs, is an electric experience.

Quote is from Street Portraits 1946-1976: The Photographs of Jules Aarons, Kim Sichel, ed. (Stinehour Press, 2002), p. 10.

Photos: Untitled (West End, Boston), 1947-53 (top). Lounging, North End, 1950s (bottom).

For more info about the exhibition at the Boston Public Library, look here. To see more photos by Jules Aarons, look here and here. There is also a Facebook page dedicated to Aarons here.

Landay … suddenly, he’s …. everywhere! (Rec’d via BPL Facebook feed)

It’s futile to resist me, Alex.

Thanks for this post, I didn’t know of Aarons. Wonderful gritty pictures. I haven’t read your Strangler but these images inspired me to. I suppose that yeah it is futile to resist you.

Having had the opportunity to work with Jules was a gift. He was a remarkable man. Aarons’ images were never posed; instead, the richly narrative prints reveal a “moment” in time which lives on after the shutter has closed. He has given us a 30+ year pictorial history beginning after World War II; not only mid-century Boston, but from around the world in such places as France, London, Peru, Japan, Spain, Greece, Mexico, and Portugal.

It’s wonderful to have his work on display at the BPL where so many will have the opportunity to enjoy them.

Thanks for posting your thoughts on Jules Aarons and the Boston exhibit. I watched This Old House tonight and they are doing his home. His son talked about growing up there and watching his dad in the dark room. The house is now owned by another family. TOH did a great film feature on Jules Aarons. I wish they had posted a link, I would love to watch it over and over. Rita Sokolowski