Gorgeous images of New York City by photographer Barbara Mensch. Some background information about Barbara Mensch is here.

Archives for 2009

“No battle plan…”

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

Lawrence Lessig on the Google book search settlement

Will Google Books, the audacious attempt to digitize every book ever written, have the perverse effect of making books — and ideas — less available, less ubiquitous, less free? Will copyright laws require that most of the books written in the last century be excluded from the new digital online library? Is this progress? This is Lawrence Lessig speaking at Harvard two weeks ago. Lessig’s presentation runs about 28 minutes followed by a 15-minute Q&A.

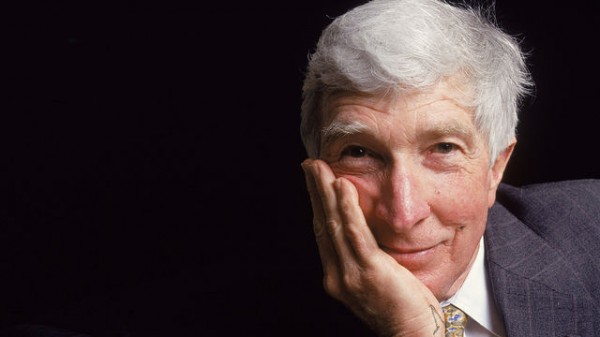

Remembering Updike the Father

John Updike’s son David, also a writer, has a lovely piece in the Times’ Paper Cuts blog. It is a eulogy for his father which he delivered at a tribute in March at the New York Public Library. I found this passage particularly touching:

But for someone who was getting famous, my father didn’t seem to work overly hard: he was still asleep when we went to school, and was often home already when we got back. When we appeared unannounced, in his office — on the second floor of a building he shared with a dentist, accountants and the Dolphin Restaurant — he always seemed happy and amused to see us, stopped typing to talk and dole out some money for movies. But as soon as we were out the door, we could hear the typing resume, clattering with us down the stairs.

My own sons, now five and eight, perceive me the same way, I think. To kids (and others), a writer at work does not seem to be doing much. They can’t understand that I am hard at it whether I am typing like mad or staring blankly out the window. Maybe this is true of all desk-work. Well, at least I have this one thing in common with Updike.

I admit, I feel a strange, vaguely filial attachment to writers of my father’s generation, especially Roth, Updike and Doctorow, whose books I grew up reading. Anyway, read the whole Updike eulogy. You won’t be sorry.

In the meantime, for all my fellow unmentored writers out there, here is Updike in 2004 with some fatherly advice for young writers.

The rest of the interview is here.

Crime novels and entertainments

I was interested to read on Sarah’s blog about the fuss John Banville raised recently. Banville said, undiplomatically, that he writes more quickly and easily as crime writer “Benjamin Black” than he does writing literary novels under his own name. There were hurt feelings, suggestions that Banville was “slumming,” and the author felt compelled to issue a foot-shuffling clarification. “The distinction between good writing and bad,” he said, “is the only one worth making.”

That is so obviously untrue — lots of distinctions beyond good/bad are worth making — that Banville must have held his nose while typing it. The whole thing reminds me of Michael Kinsley’s definition of a Washington gaffe: when a politician inadvertently tells the truth in public.

Does anyone really doubt that an author would find it easier to write freely when he is working in a genre with established conventions? There are plenty of challenges to genre writing, of course. The writer can stick to the conventions, subvert them in various ways, update them, etc. But the rules do exist. The relative difficulty in writing “literary” novels is not that there aren’t models to follow; non-genre writers mimic older stories all the time. The difficulty — at least the one Banville meant — is that storytelling conventions are less clear and less important. The writer is at sea. That is why literary writers like Banville, Richard Price, and E.L. Doctorow (Billy Bathgate) feel relieved when they come to crime writing. Finally, there is a roadmap, a method to plotting the story. As a crime writer, I am thankful for that roadmap every day.

It is also obvious that genre novels place a higher priority on entertaining the reader. This is the umpteenth rehash of Graham Greene’s old distinction between novels and entertainments, and the only remaining mystery is why on earth we continue to worry about it. Listen to Greene (see below) as he briefly discusses the subject. It turns out, the novels/entertainments distinction didn’t hold up very well even for the man who invented it. “Most of my novels have an element of melodrama,” Greene concedes, even the literary ones. All novels need drama, even the melo- kind.

So let’s not be so touchy, crime fans. Entertainments — yes, crime novels included — are indeed easier to write, just as Banville says. They are also generally easier to read, precisely because they take seriously the writer’s duty to entertain. Why apologize for it?

By the way, I always find it a little disconcerting to hear or see an author whose books I love. The authorial voice is one the reader creates in her own head. Greene’s actual, reedy voice is not the one I’d imagined for him. (Click below to hear him.) Yet another example of the internet revealing too much.

[jwplayer config=”Landay Audio Player” file=”/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/05-Novels-And-Entertainments.mp3″ /]

Kate’s Mystery Books closes (for now)

Kate’s Mystery Books in Cambridge closed on Saturday. Kate Mattes held an event with an army of volunteers who helped pack the place up. I stopped by and chatted briefly with Kate, who told me she plans to spend the next year or so getting her enormous inventory properly cataloged online, as well as digitizing two decades worth of book reviews. Then she may look around for a new bricks-and-mortar location if the conditions are right. In the meantime she will continue to hold author events, and her web site is still around.

It goes without saying that the city is a duller place this morning without Kate’s. Of course any number of bookshops have closed the last few years, but this loss feels particularly sad. I never knew the shop especially well, but it seemed like one of those places. It had the patina of years, and a community of readers had sprung up around it. Places like that can’t be replaced or recreated, least of all by a website.

But there’s no use sighing over the blandification of Cambridge, where a funky overstuffed bookstore in an old rambling red Victorian once would have seemed right at home. Or the general extinction of bookstores run by real, live book lovers. Things change. It sucks, but what can you do?

So I will just thank Kate for supporting me from the day my first book arrived and hand-selling my books ever since. I’m sure there is a marching band of writers out there who feel the same way. Thank you, Kate. We’ll see you around.

Makers vs. Managers

I’ve written before about the need for writers and other artists to have long stretches of quiet, uninterrupted time to submerge completely in their work. A post is making the rounds today by the programmer and entrepreneur Paul Graham that places the artist’s workstyle in a wider context.

There are two types of schedule, which I’ll call the manager’s schedule and the maker’s schedule. The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.

When you use time that way, it’s merely a practical problem to meet with someone. Find an open slot in your schedule, book them, and you’re done.

Most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. It’s the schedule of command. But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.

When you’re operating on the maker’s schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in. Plus you have to remember to go to the meeting. That’s no problem for someone on the manager’s schedule. There’s always something coming on the next hour; the only question is what. But when someone on the maker’s schedule has a meeting, they have to think about it. …

I find one meeting can sometimes affect a whole day. A meeting commonly blows at least half a day, by breaking up a morning or afternoon. But in addition there’s sometimes a cascading effect. If I know the afternoon is going to be broken up, I’m slightly less likely to start something ambitious in the morning. I know this may sound oversensitive, but if you’re a maker, think of your own case. Don’t your spirits rise at the thought of having an entire day free to work, with no appointments at all? Well, that means your spirits are correspondingly depressed when you don’t. And ambitious projects are by definition close to the limits of your capacity. A small decrease in morale is enough to kill them off.

I quote the piece at length here because Graham gets it exactly right, but you really have to read the whole thing. I read it with a little shiver of recognition.

Of course all writers are both makers and managers at different times. The trick is to keep the two roles separate, to wall off your “maker” times, those long periods during the day when you are trying to create. It does not matter if you retreat to a dedicated workspace like Philip Roth or just a crowded coffee shop, so long as you segregate your creative-work time from ordinary, “managerial” work time. A writer’s workplace is to some extent a state of mind, a “maker” state of mind: isolated, entranced, submerged.

To non-writers, no doubt this all seems a little fussy and precious. That is because most people, not just powerful people, live in the managerial mode, shifting constantly from task to task. I am lucky my family understands that Daddy needs to go off and be alone for long periods to do his work, and they indulge me. My kids don’t know any different. To them, this is all just part of Daddy’s job and his personality. They understand, too, that I am often “distracted and cranky” when I am writing, as Stephen Dubner describes his own maker times. All part of the writing life, I suppose. Still, as a writer it helps to have myself explained to myself, as Paul Graham has done today.

Update: Daniel Drezner, a professor at Fletcher, adds an important thought about the particularly high cost of interruptions in the early stages of a creative project:

I think the problem might even be worse than Graham suggests. Speaking personally, the hardest part of any research project is at the beginning stages. I’m trying to figure out my precise argument, and the ways in which I can prove/falsify it empirically. While I’m sure there are people who can do that part of the job with a snap of their fingers, it takes me friggin’ forever. And any interruption — not actual meetings, but even responding to e-mail about setting up a meeting — usually derails my train of thought.

The early stages of a novel — or any creative project, I imagine — are equally tentative and fragile.

“Free” and the Future of Publishing

I had an interesting conversation on Saturday with Bruce Spector, the founder and CEO of a new web service called LifeIO. (See the end of this article for an explanation of what LifeIO is all about.) Bruce was part of the team that developed WebCal, which Yahoo! acquired in 1998 to form the core of its own calendar service, so he has been watching the web with an entrepreneur’s eye for some time now and he had an interesting take on the whole “free” debate and how it might apply to book publishing.

If you somehow missed the recent back-and-forth about Chris Anderson’s book Free, read the pro-“free” comments by Anderson, Seth Godin and especially Fred Wilson, and the anti-“free” perspective by Malcolm Gladwell and Mark Cuban, among many others. This piece by Kevin Kelly, not directly about “free,” is very good, too.

For the uninitiated, the issue boils down to this: The marginal cost of delivering a bit of information over the web — a song, a video, a bit of text like this one — is approaching zero. As a result, information is increasingly available, and consumers increasingly expect to get it, for free. So traditional “legacy” information-sellers like musicians or movie studios or newspapers, whose actual costs are very far from zero, have to figure out how to turn free-riders into paying customers — and fast, before they go out of business. Fred Wilson’s answer is “freemium“: you lure the customer in with a free basic service, then up-sell the heaviest users to a premium version of your product. As Wilson puts it, “Free gets you to a place where you can ask to get paid. But if you don’t start with free on the Internet, most companies will never get paid.”

How does all this apply to book publishing?

Here are some of Bruce Spector’s ideas. He is a great talker, though, and a summary like this doesn’t do him justice. Also, this was a private conversation, but Bruce kindly gave me permission to repeat some of his comments here.