Beautiful images, mostly of Philadelphia, by photographer Michael Penn. Above: “Storm Over Fishtown,” 2008.

Official website of the author

Beautiful images, mostly of Philadelphia, by photographer Michael Penn. Above: “Storm Over Fishtown,” 2008.

I don’t want to turn this blog into a sellathon for my books. I am quite bad at self-promotion, probably because it makes me so uncomfortable.

But as I’ve been transferring material from my old web site to this new blog, I ran across a review of The Strangler that I particularly relished and want to share here. It was not widely read, I am sure. It appeared in Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, the professional journal of the local bar, on May 28, 2007. I would have missed it myself if some lawyer friends had not pointed it out to me.

I love this review because it was written by a veteran criminal defense lawyer who actually knew Boston in the Strangler era and because it focuses on the accuracy of the historical detail. Factual accuracy is lost on most readers. They show up for the story, as they ought to do. The setting may seem vivid and convincing to them, but they have no way of judging its authenticity and they don’t give a damn anyway.

When I first took up writing about crime, as a former A.D.A. I resolved that my books would be accurate to the last detail. They would be “true.” Cops and lawyers would pick them up and nod their heads in recognition: “That’s how it really is!” I quickly learned how foolish that was. It is more important to tell a good story than an accurate one, better to be credible than authentic, realism is not reality, etc., etc. These are basic rules. But the truth is, authenticity still matters to me, probably more than it should.

Local writer pens novel of killer’s stranglehold on Boston

By Norman S. Zalkind

“The Strangler,” by Newton’s own William Landay, is an extraordinary portrayal of the underbelly of Boston in the early 1960s. It is Landay’s second contribution to the crime-novel genre, his first being “Mission Flats” (the fictional name of a gritty city neighborhood in Boston), in which he showed his skill at turning out a page-turner.

Having grown up in and around Boston when the events portrayed in Landay’s latest work took place, I am amazed at his ability to accurately reconstruct one such history-making event: the tragic destruction of Boston’s West End neighborhood and its replacement with a so-called urban-renewal project that destroyed a vibrant, working-class immigrant community.

Landay’s story of an infamous strangler feels like the Boston-based movie, “The Departed,” with non-stop violence seen through the eyes of the three Daley brothers: Ricky, the skilled burglar; Michael, the Harvard-trained lawyer; and Joe, the World War II veteran, compulsive gambler and Boston cop who is corrupted by his addiction.

The Boston Strangler investigation was on everyone’s mind in the Boston of 1963. A killer had taken the lives of a dozen victims, and the city was shaken.

Landay, a Boston College Law School graduate and a former assistant district attorney, postulates the theory that Albert DeSalvo, who confessed to the crimes (and was later murdered in prison), was really not The Strangler. Many in the legal community agree with Landay’s thinking.

But this attorney/author dismisses any suggestion that his background in criminal justice might explain his facility for writing on that topic. “I am leery of my own credentials,” he told The Boston Globe in a recent interview. “People look at me and focus on the fact that I was an assistant DA and project all sorts of things on my books, as if that is some sort of guarantee of authenticity. But the credential guarantees nothing.”

Nonetheless, Landay can spin a tale of murderous intrigue. “The Strangler” is fast-paced, filled with relentless suspense and mayhem. The Daley boys’ father, a Boston police officer, is killed under mysterious circumstances, and the brothers suspect their father’s partner, Conroy, of the killing.

The story becomes more complicated when, after the father’s death, Conroy moves in with Joe Daley Sr.’s widow, Margaret. More complications arise when Margaret is attacked by a man the sons believe is the real “Strangler.”

Joe, the cop, becomes a pawn for the mob, but he is both good cop and bad cop at the same time. The good-cop side of Joe leads him to investigate the forced removal of families from the West End. When he stands up to the mob, and doesn’t get his burglar brother Ricky to return diamonds he allegedly stole, Joe and Ricky become objects of mob contracts.

Former ADA Landay is able to capture the criminal-defense scene the way it was in the early 1960s. The defense bar was dominated by natives of Massachusetts — and Boston in particular. The colorful F. Lee Bailey and others of his ilk — Joe Balliro, Bill Homans and Paul Smith, among them — could definitely have been the lawyer characters in this novel. Boston’s non-white-collar criminal defense bar is today still dominated by locals, but they are nothing like their legal forebears of 40 years ago.

Landay’s constant use of local street language reveals his in-depth knowledge of a storied era and brings color and humanity to his writing. He reveals his relative youth only when he has the Boston detective carrying 9 mm firearms instead of the .38-caliber guns that the police used in that earlier time.

This lawyer novel is most impressive in its focus on crime and the city. It is a great fast read that unfolds like a screenplay. You will be impressed with the way the writer integrates homicide investigations, political corruption, mental illness, organized crime, love, humor and much more. ♦

Norman S. Zalkind is a longtime Boston criminal-defense attorney.

As for that gun, it is the one detail of the book that I changed when The Strangler was reissued in paperback. Joe Daley now carries a .38 as he should, thanks to Mr. Zalkind.

For more than 10 years, the intricate, multiseason narrative TV drama has exercised a dominant cultural sway over well-educated, well-off adults. Just as urbanish professionals in the 1950s could be counted on to collectively coo and argue over the latest Salinger short story, so that set in the 2000s has been most intellectually, emotionally, and aesthetically engaged not by fiction, the theater, or the cinema but by The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, The Wire, Deadwood, The Shield, Big Love.

— Benjamin Schwartz, “Mad About Mad Men,” Atlantic Monthly

So that’s where all the readers went.

Just for kicks, courtesy of Wordle.net, here is the text of The Strangler displayed as a word cloud, a visual representation of the most frequently used words in the novel. Not sure how much this tells you, really. The characters’ names dominate, as you might expect. Other prominent topics show up as well: Boston, cops/police, brother. The surprise is that the F-word appears, and not once but twice, including the all-important adjectival or gerund form, fuckin’. I know some authors shy away from profanity even in books that are violent or sexually graphic or otherwise aimed at adults. But to me it seems phony to portray street thugs speaking the Queen’s English, and perverse to blush at using a dirty word but not at lurid descriptions of gory violence. Even so, I hadn’t realized I used the word that much.

Jonah Lehrer on the neuroscience of how our brains process the words we read and how that process will be affected by ebooks:

… most complaints about E-Books and Kindle apps boil down to a single problem: they don’t feel as “effortless” or “automatic” as old-fashioned books. But here’s the wonderful thing about the human brain: give it a little time and practice and it can make just about anything automatic. We excel at developing new habits. Before long, digital ink will feel just as easy as actual ink.

Interesting: the technology of ebook readers will improve, but so will our brains’ ability to use them.

David Benioff’s novel City of Thieves is a great speed-read. Fast, smart, cinematic. Loved it.

Yesterday I saw Jane Campion’s movie “Bright Star,” about the doomed romance between the poet John Keats and Fanny Brawne, and I liked it very much. How could I not like it? The romantic hero is a writer. You don’t see that very often.

Writers make bad film protagonists because the real work of writing is unfilmable. A writer at work is doing nothing more picturesque than scribbling on a pad or, worse, staring into space. The “action,” such as it is, takes place in his mind. So the struggle to create has to be extroverted, acted out: the writer balls up a piece of paper and flings it across the room in frustration. Personally, I have never balled up a manuscript page and flung it across the room. I work on a computer. Most writers do now, which should spell doom for this particular film cliché, a blessing for which we should all be thankful.

There are good movies about writers, of course, but they are generally not about the work itself. Successful writer movies — “Capote,” for example — include virtually none of their subjects’ actual prose. They are not about what’s inside the books; they are about the struggle to make the books.

This is why “Bright Star” is such an exceptional writer movie. Keats’s poetry is a constant presence in the film. It is read aloud by characters within scenes and in voice-over. The end credits alone, in which the actor Ben Whishaw reads the “Ode to a Nightingale” in its entirety, is worth the price of the ticket. Keats’s letters, too, are woven into the dialogue. The film is about a mood, and it is the same mood that Keats’s poetry captures so well — gloom, melancholy, languor, longing. The movie and the poems are written in the same key, so the poetry actually enhances the film just as the usual movie devices do, cinematography, music, and so on.

It is surprising that there are so few movies about poets. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a single one. But poetry and film work well together. E. L. Doctorow has written,

Film de-literates thought; it relies primarily on an association of visual impressions or understandings. Moviegoing is an act of inference. You receive what you see as a broad band of sensual effects that evoke your intuitive nonverbal intelligence. You understand what you see without having to think it through with words.

Yes, all right, it is a visual medium. But poetry does something similar. It “literates” emotion, it evokes moods without ever quite naming them. Sometimes it describes states of mind that have no name, that never coalesce into definite thoughts, and therefore can’t be thought through, only felt. You can understand a poem without quite being able to put its meaning into words.

At several points “Bright Star” seems about to tip over into preciousness, as so many period costume dramas do. Ben Whishaw, as Keats, is delicate looking. He stares dreamily at flowers or coughs with tuberculosis. (It is really Fanny’s movie. If there is any justice, the role will make a star out of Abbie Cornish.) What makes him affecting is the poems. No wonder Fanny fell for him — he’s John Keats. Whatever flaws the movie may have, I can’t think of any other that incorporates a writer’s actual words so much and so well.

The animating idea of The Strangler was to recreate Strangler-era Boston, to bring the lost city to life so convincingly that readers would have the immersive three-dimensional experience of actually being there, walking the streets, brushing shoulders with the people. Period authenticity was important: the original working title of the book was The Year of the Strangler.

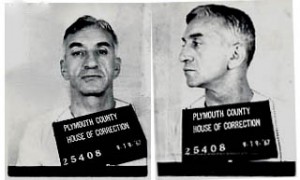

Of course reanimating the actual city required that a few prominent Bostonians appear undisguised, or nearly so, including gangsters, cops, and politicians. In the original draft, these characters were accurately named and described. The mob boss Capobianco, for example, was called by his real name, Gennaro Angiulo. The historical Gerry Angiulo ran the Boston mob during my childhood in the 1970s. In 1963 and ’64, when The Strangler takes place, he was just consolidating his power.

On the eve of the book’s publication, I got a call from a lawyer at Random House asking about some of these historical figures, including Angiulo. “Is he still alive?” the lawyer wanted to know. Apparently libel laws are stricter when the subject is living. Angiulo was 87 years old then, but still alive in a federal prison. So his name had to be changed. To further insulate the book from a libel charge, Angiulo had to be mentioned by name in the book so we could plausibly deny that my character Capobianco was an Angiulo stand-in. After all, we could argue, there is Angiulo standing next to Capobianco — how could they be the same person? All this sensitivity about the man’s reputation seemed a little ridiculous to me. How was it possible to libel a murderer and convicted mafioso like Gerry Angiulo? But I did not insist, and shortly before publication the character was rechristened Charlie Capobianco. Still the facts remain: the novel’s description of a “born bookie” who became a mob boss — his physical appearance, his biography, his North End headquarters, his bookmaking operation — all are meticulously faithful to the life of Gerry Angiulo. (The libel issue is moot now. Gerry Angiulo died at the end of August, at age 90. His funeral procession required a flatbed truck to carry the 190 bouquets of flowers.)

[Read more…] about Angiulo, Barboza and fictionalizing the Boston Mob