“All good writing is swimming under water and holding your breath.”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, from an undated letter to his daughter Scottie, reprinted in The Crack-Up (1945)

Official website of the author

“All good writing is swimming under water and holding your breath.”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, from an undated letter to his daughter Scottie, reprinted in The Crack-Up (1945)

Here, on fine long legs springy as steel,

You can watch Kooser read this poem on video here.

Toward the end, writing a novel is a race against the clock. Deadlines that once seemed absurdly far off suddenly loom into view. The story itself demands that you write faster, too, with more urgency, so that the reader will feel the acceleration and she will be pulled along with you to the finish. That is the stage of writing I am entering now, and I am dreading it.

I am behind schedule, as usual. It seems unlikely I will make my internal deadline of January 1 for a completed manuscript, but I am going to kill myself trying. The real deadline, when the manuscript is actually due on my editor’s desk (well, in her email inbox), is April 1, and the cost of missing it — the loss of my publishers’ trust, the loss of future prospects — is simply too high for a midlist, erratically productive writer like me to survive at this point in my career. So the internal deadline remains January 1. That should leave me enough time for rewriting and polishing. Alas, November and December will not be much fun for me.

The good news is that the book itself is working. I have never been one of those writers who feel, as many claim to, that the characters come alive and act on their own while the writer merely watches, furiously writing down the action like a medium at a séance. It is always work for me, always an uphill push. Still, when it is right, something happens: the material feels rich, it generates ideas organically, the direction of the story becomes more obvious. With this book, thankfully, that something has happened.

In terms of pages, I am probably only halfway through the manuscript, maybe a bit further. In terms of story, I have reached act three, the final build-up to the climax. The story concerns a Boston prosecutor named Andy Barber whose teenage son is accused of murder. (A film producer who read the existing manuscript described it in perfect Hollywood-speak as Presumed Innocent meets Ordinary People, which, I am embarrassed to say, is pretty close.) As act three opens, the case goes to trial. I have never written a courtroom sequence before, but I am confident I can. I have been in court many, many times in my prior life as a prosecutor. More important, the courtroom is such an inherently dramatic arena and trials are so scripted and rules-bound that there is a ready structure for the storytelling. So again, this is all to the good.

I continue to labor over the title. The working title remains Blood Guilty but I detest it. This is a bigger problem than you might imagine. The title crystallizes the story in my mind. Not having a title makes the whole project feel foggy and uncertain to me. I have churned up alternatives — Seed, The Good Father, In Our Blood, many others — but each seems worse than the last. It is some comfort to remember that Fitzgerald never liked the title The Great Gatsby for his masterpiece and he tried to change it right up to the time the book went to press. The Great Gatsby, it must be admitted, is not a great title, so maybe this is less of an issue than it seems at the moment.

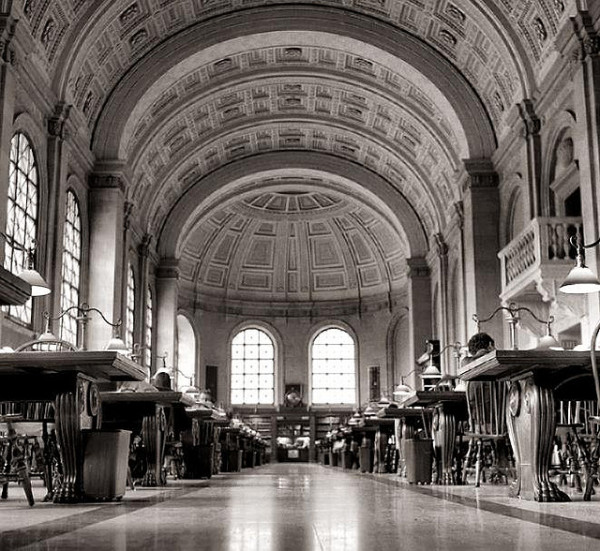

That is where it stands. I am turning for home. It is a difficult stage in the process, but then they’re all difficult. I am back to writing every morning at the Boston Public Library reading room (pictured above), though my old quota of a thousand words a day is not going to get it done anymore. I am now just writing as much as I can every day until I run out of gas.

I am not complaining. It is a privilege to do what I do. There are only a handful of full-time novelists on the planet, meaning novelists who make a decent living at it without the need for a day job. So I am blessed and I understand that. Still, these next eight weeks are going to suck.

Photo: “Study” (main reading room of the Boston Public Library) by Haydnseek (link).

I was struck by this ad for Levi’s jeans, which features a few stanzas from Walt Whitman’s poem “Pioneers! O Pioneers!” If you dislike the spot, I understand. The bullshit factor is high even by advertising standards: half-naked slackers as “new American pioneers,” hawking these surpassingly American jeans that are actually made overseas, using a poet who probably never heard of blue jeans. And all this solemnity over … pants. But to me this looks like an ad for Whitman, not Levi’s. When was the last time poetry looked this cool or sounded this stirring? Whether the ad will actually sell jeans I have no idea. But it will get plenty of people asking, “What is that poem?” And that is a very good thing.

By the way, the actor reading these lines is Will Geer, recorded in 1957, before he became Grandpa Walton.

The publication of This Side of Paradise when he was 23 immediately put Fitzgerald’s income in the top 2 percent of American taxpayers. Thereafter, for most of his working life, he earned about $24,000 a year, which put him in the top 1 percent of those filing returns. Today, a taxpayer would have to earn at least $500,000 to be in the top 1 percent. … Most of his earnings came from the short stories and, later, the movies. His best novels, The Great Gatsby (1925) and Tender Is the Night (1934), did not produce much income. Royalties from The Great Gatsby totaled only $8,397 during Fitzgerald’s lifetime.… When he died in December 1940, his estate was solvent but modest — around $35,000, mostly from an insurance policy. The tax appraisers considered the copyrights worthless. Today, even multiplying Fitzgerald’s estate by 30, it would not require an estate tax return.

— William J. Quirk, “Living on $500,000 a Year: What F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tax Returns Reveal About His Life and Times”

Over the course of the [Frankfurt Book] Fair various players offered phrases such as “a digital manifestation of what was a book” and “long-form narrative delivered digitally” and “story-telling” and “immersive text-only experiences,” and it is clear that the reason for such a profusion of vague terms is not obtuseness but a recognition that we’re not replacing one static-priced unit (pBook) with another static-priced unit (eBook), but finding that our single massive unidirectional pBook supply chain is now just one component of a tremendously variegated set of producer-consumer relationships.

Stieg Larsson’s detective character, Lisbeth Salander, the “girl with the dragon tattoo,” was apparently inspired by Pippi Longstocking. According to a former work colleague,

Stieg got the idea for the character Lisbeth Salander after a discussion during a break from work. They were talking about how different characters from children’s books would manage and behave if they were alive and grown up. Stieg especially liked the idea about a grown up Pippi Longstocking, a dysfunctional girl, probably with attention deficit disorder who would have had a hard time finding a regular place in the “normal society,” and he used … those characteristics when he created Lisbeth Salander.

More clips from this interview here.