I have been reading Little Dorrit the last couple of weeks and I am engrossed, even though life has been a little chaotic. I have been working feverishly on my own new novel, cranking out the last few chapters in rough draft. At the same time, my kids are on school vacation and our house has been unusually tumultuous — which is saying something.

Still, nothing in my life could possibly compare to the tumult in Dickens’s. He was roughly my age when he wrote Little Dorrit, completed in 1857 when Dickens was 45. (I am 46.) Here is Edmund Wilson’s description of this period in the great man’s life.

Dickens at forty had won everything that a writer could expect to obtain through his writings: his genius was universally recognized; he was feted wherever he went; his books were immensely popular; and they had made him sufficiently rich to have anything that money can procure. … Yet from the time of his first summer in Boulogne in 1853 [when Dickens was 39], he had shown signs of profound discontent and unappeasable restlessness; he suffered severely from insomnia and, for the first time in his life, apparently, worried seriously about his work. He began to fear that his vein was drying up.

It is hard to imagine a novelist achieving this sort of stardom today, even one whom Wilson considered the best England had produced since Shakespeare. It is poignant, too, to imagine a man so fantastically successful yet so intractably unhappy. Dickens’s life disproves the romantic notion that writing is good therapy: he fictionalized his painful memories in book after book but was tormented right to the end.

I am dying to learn more about him. Next up for me will be Michael Slater’s new biography, apparently wonderful, Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing, fortuitously published just as I go on a Dickens kick.

(For the record, the quote is from Edmund Wilson’s essay “Dickens: The Two Scrooges” (1939), available in the Library of America collection of Wilson’s Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s & 1940s.)

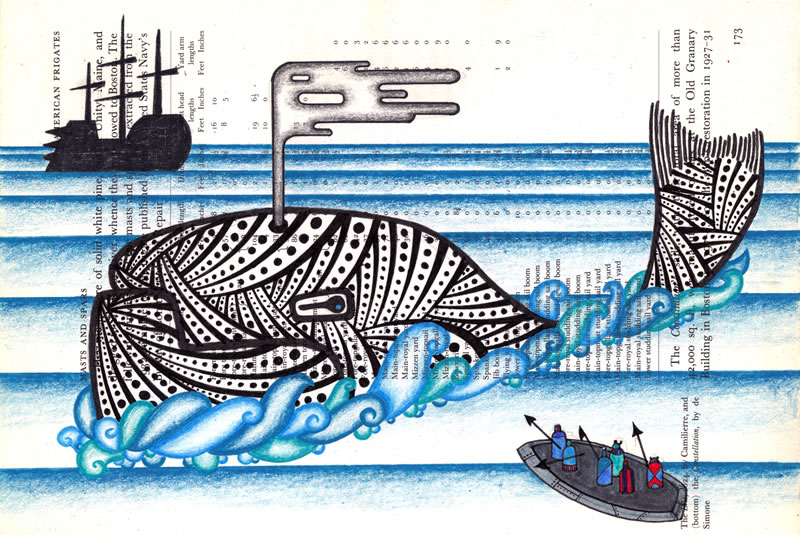

Matt Kish, whose

Matt Kish, whose