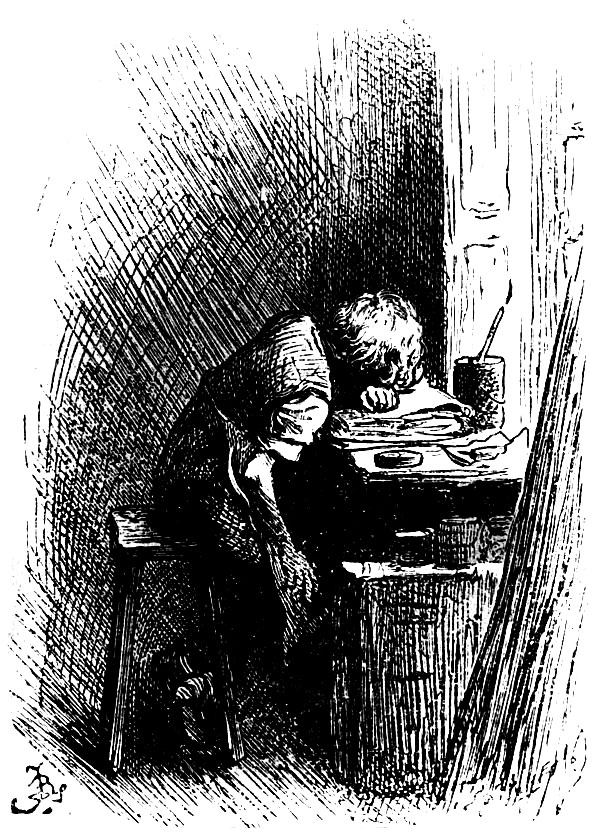

At the age of 12, thanks to his father’s bankruptcy, Dickens found himself working in a rat-infested warehouse that produced bottles of liquid shoe polish. The work itself probably lasted for no more than a year, but it left scars on his imagination that never properly healed. His rage at social injustice, his sensitivity to the fate of abandoned children, his never-satisfied hunger for financial and emotional security: all this can be traced back to his time sticking labels onto bottles of Warren’s blacking. So can the routines he adopted to tame life’s mess and confusion. He would whip out a comb whenever a hair was out of place, conducted regular inspections of his children’s bedrooms, and rearranged the furniture when he stayed in hotels, so that everything was always in its proper place.

In his writing, too, Dickens sought to create order out of chaos. His sprawling plots were carefully parcelled out in weekly or monthly installments. His bulging lists of characters were allowed to run riot across the page, but were eventually tied down to the standard fates of fictional Victorians: marriage, exile, death. His “clutching eye” produced passages that teem with the clutter of ordinary life, while allowing some odds and ends to take on a strangely proverbial quality, as when a “sickly bedridden humpbacked boy” in Nicholas Nickleby is described enjoying some hyacinths “blossoming in old blacking-bottles,” like a little SOS message from Dickens’s childhood that has suddenly bobbed to the surface of his prose.

— Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, “Charles Dickens”

Image: Fred Bernard, “Dickens at the Blacking Warehouse,” from The Leisure Hour (1904) (source).

Beautifully illustrated quote. Thank you for sharing.

see Charles Dickens and the blacking factory, by Michael Allen for the very latest research on this pivotal part of Dickens’ childhood.